I’ve tried to keep musings on research methodology & epistemology mostly off this blog (they are mostly to be found over on my just-out-of-stealth-mode ‘Open Data Impacts’ research blog), however, for want of somewhere better to park the following brief(ish) reflections:

- Content Analysis is a social science method that takes ‘texts’ and seeks to analyze them: usually involving ‘coding’ topics, people, places or other elements of interest in the texts, and seeking to identify themes that are emerging from them.

- One of the challenges of any content analysis is developing a coding structure, and defending that coding structure as reasonable.In most cases, the coding structure will be driven by the research interest, and codes applied on the basis of subjective judgements by the researcher. In research based within more ‘objective’ epistemic frameworks, or at least trying to establish conclusions as valid independently of the particular researcher – multiple people may be asked to code a text, and then tests of ‘inter-coder reliability‘ (how much the coders agreed or disagreed) may be applied.

- With the rise of social bookmarking sites such as Delicious, and the growth of conventions of tagging and folksonomy, much online content already has at least some set of ‘codes’ attached.For example, here you can see the tags people have applied to this blog on Delicious.

- Looking up any tags that have been applied to an element of digital content could be useful for researchers as part of their reflective practice to ensure they have understood an element of content from a wide range of angles – beyond that which is primarily driving their research.

- (With many caveats) It could also support some form of ‘extra-coder reliability’ providing a check of coding against ‘folk’ assessments of content’s meaning.

- The growth of the semantic web also means that many of the objects which codes refer to (e.g. people, organizations, concepts) have referenceable URIs, and if not, the researcher can easily create them.Services such as Open Calais, and Open Amplify also draw on vast ‘knowledge bases’ to machine-classify and code elements of text – identifying, with re-usable concept labels, people, places, organizations and even emotions. (The implications of machine classification for content analysis are not, however, the primary topic of this point or post).

- Researchers could chose to code their content using semantic web URIs and conventions – contributing their meta-data annotations of texts to either local, or global, hypertexts.For example, if I’m coding a paragraph of text about the launch of data.gov.uk, instead of just adding my own arbitrary tags to it, I could mark-up the paragraph based on some convention (RDFa?), and reference shared concepts.From a brief search of Subj3ct for ‘data’, I quickly find I have to make some fairly specific choices about which concepts of data I might be coding against, although hopefully if they have suitable relationships attached, I may be able to query my coded data in more flexible ways in the future.

- All of this raises a mass of interesting epistemic issues, none of which I can do justice to in these brief notes, but which include:

- Changing the relationship of the researcher to concept-creation – and encouraging both the re-use of concepts, and the shaping of shared semantic web concepts in line with the research;

- The appropriateness, or not, of using concepts from the semantic web in social scientific research, where the relatively objectivist and context free framing of most current semantic web projects runs counter to often subjectivist and interpretivist leanings within social science;

- The role of key elements of the current web of concepts on the semantic web (for many social scientific concepts, primarily Wikipedia via the dbpedia project) where the choice of what concepts are easily referenceable or not depends on a complex social context involving both crowd-sourcing and centralised control (ref the policies of Wikipedia or other taxonomy / knowledge base providers).

- The actual use of existing online tagging, and semantic web URIs as part of the content analysis coding process (or any other social scientific coding process for that matter) may remain, at present, both methodologically challenging, and impractical given the available tools – but is worth further reflection and exploration.

Reflections; points to literatures that are already exploring this; questions etc. all welcome…

[Summary: Yes, it’s time for another 2.0 titled workshop idea. Political theory at

[Summary: Yes, it’s time for another 2.0 titled workshop idea. Political theory at

And the answer to the straight question of 'Should our local authority be on my space of Facebook?' turns out to be a very qualified definitely maybe.

And the answer to the straight question of 'Should our local authority be on my space of Facebook?' turns out to be a very qualified definitely maybe.

Q: If 60% of your target population for an activity or project are going to a particular space, and you can advertise there for free… would you do it? What would you have to think about in making that decision?

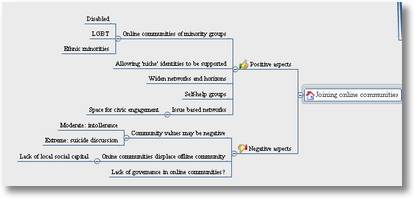

Q: If 60% of your target population for an activity or project are going to a particular space, and you can advertise there for free… would you do it? What would you have to think about in making that decision? Joining a group on a Social Networking Site is a very quick action. Groups can have a far better 'sign up' rate that an e-mail newsletter might (4). And the informal quick message to group members may be received better than the carefully edited and formatted eat-mailing. But a group is also usually a space for dialogue.

Joining a group on a Social Networking Site is a very quick action. Groups can have a far better 'sign up' rate that an e-mail newsletter might (4). And the informal quick message to group members may be received better than the carefully edited and formatted eat-mailing. But a group is also usually a space for dialogue. Question your hesitancy. Understand your reasons. Check against your aim and mission.

Question your hesitancy. Understand your reasons. Check against your aim and mission.