[Cross-posted from Connected by Data blog]

It’s been a week of both thinking big about how we might, in the coming months and years, shift public and policy narratives about collective data governance, and focussing in on the details of what it might mean in practice to make data governance more participatory. In the iterative process of building out our case study database, and reviewing reports from a number of public dialogues, citizen’s juries and participatory processes linked to data governance, I’ve been reflecting on three themes, outlined under inevitably alliterative headings below.

Defaults and decisions

Skimming the Ada Lovelace review on UK Public Attitudes to regulating data and data-driven technologies reveals a fairly clear picture, and one backed up by many of the data dialogue reports I’ve read this week , that the public want to see more and better regulation of data, and expect innovative uses of data to be aligned with the public good.

At the same time, the Ada Lovelace review finds that “more research is needed on what the public expects ‘better’ regulation to look like” and ”determining what constitutes ‘public benefit’ from data requires ongoing engagement with the public”.

Having noticed that a lot of the cases I’ve gathered so far of public dialogue around data governance tend to inform, or design, fairly general principles or recommendations on how data should be handled, I’m finding it useful to think about participatory data governance on two levels:

1) How should public input shape the defaults that are in place for any uses of data?

There may be different defaults for different sectors, or potentially for different user groups (although Afsaneh Rigot’s recent report on Design from the Margins would suggest there are strong advantages in setting the overall default based on the needs of those most affected by a technology).

Not every organisation with data to govern will necessarily need to run its own engagement process to identify the right defaults: in many cases, desk research might identify clear public-backed principles to work with.

The legitimacy of any defaults may be affected by the extent to which they are derived from considering the particular impacts that a category or type of data may have, and the extent to which populations and communities affected by those impacts were part of developing the defaults.

2) What are the appropriate mechanisms for public engagement in the specific decisions that put those defaults into practice?

Where default setting might be periodic or one-off, there are many aspects of data governance which require day-to-day engagement. Where broad public engagement might be important for setting defaults, making decisions might require more focussed approaches, potentially with participants who have more background, training or ongoing role. I’m particularly interested in the coming weeks to try and explore different models being applied to data governance here: whether focussed on shaping decisions, sharing decisions, or providing scrutiny to decisions made.

The purpose of participation

I’ve been thinking a lot this week about the distinction between different institutional designs for data governance (including novel proposals for trusts, commons and co-ops), and questions of how decisions actually get made whatever the institutional structure. I was particularly struck by this critical piece from Rachel Adams at Research ICT Africa on the problems of reaching for a data trusts model in an African context.

I’ve found it helpful (this week at least!) to break down my thinking as follows:

- Fundamentally, participation aims to align the outcomes of any process with the interests of those affected by it.

(This is compatible with recognising that some interests, and the way people or communities understand or articulate them, are not fixed, and may be refined or revised through participatory process).

- In the context of democratically governed public authorities, competitive markets, and/or a balance of power between actors, then participatory processes can help to align the interests of data powers and communities; but

- In conditions of vastly unequal power, other institutional mechanisms are required to create conditions in which the interests of authorities or firms and communities will end up aligned.

Mechanisms, for example, like trusts, commons or co-ops that seek to change where decisions are made, and what the backstops are to protect against individual, private or external interests being put above community or collective interests.

Thinking about the purpose of participation in terms of aligning actions or outcomes from data governance with the interests of the populations affected also brings into relief the points that (a) different communities may have interests that are not aligned, or even entirely compatible; and (b) a lot hinges on how the community whose interests are to be explored is defined.

Components, connections and configurations

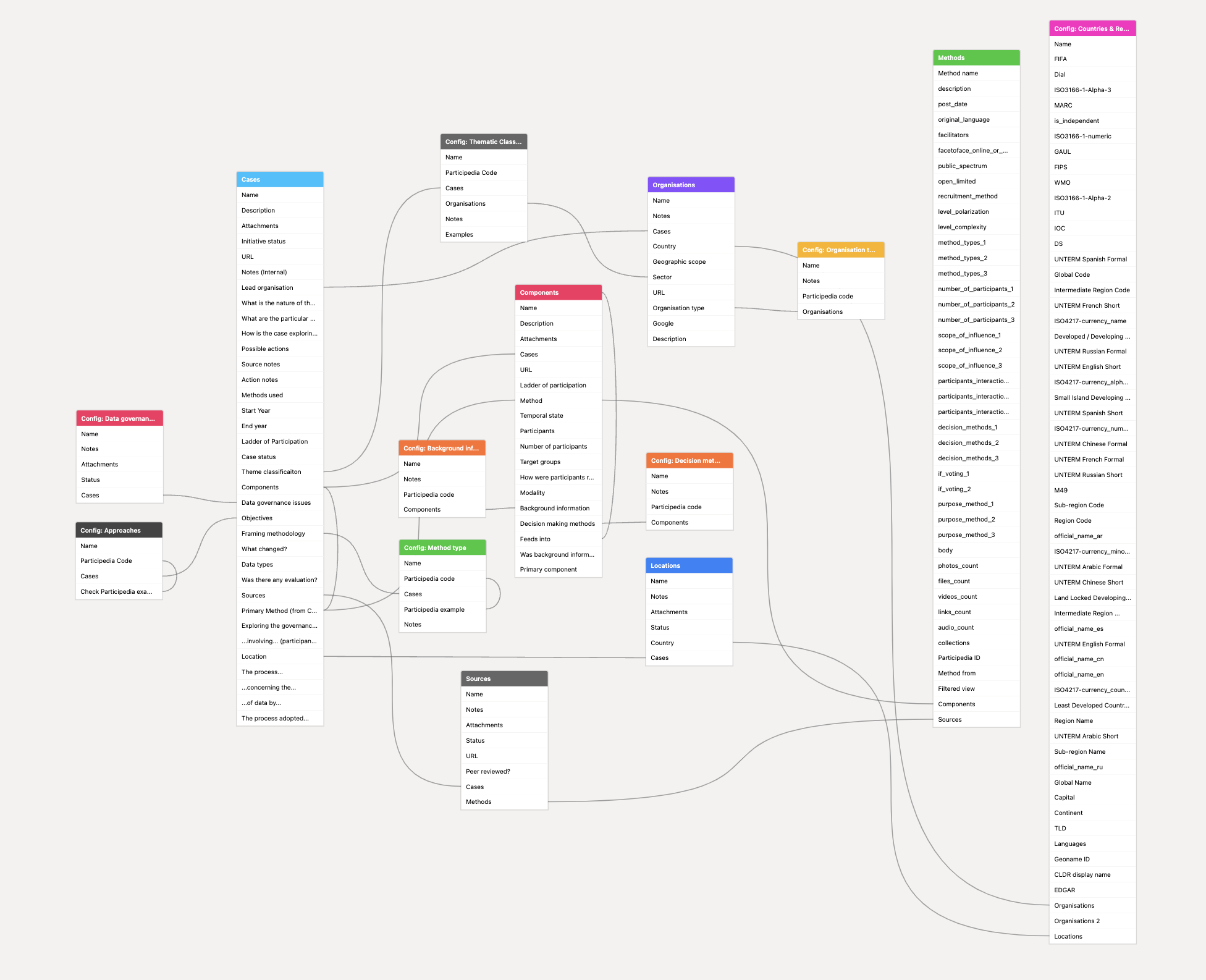

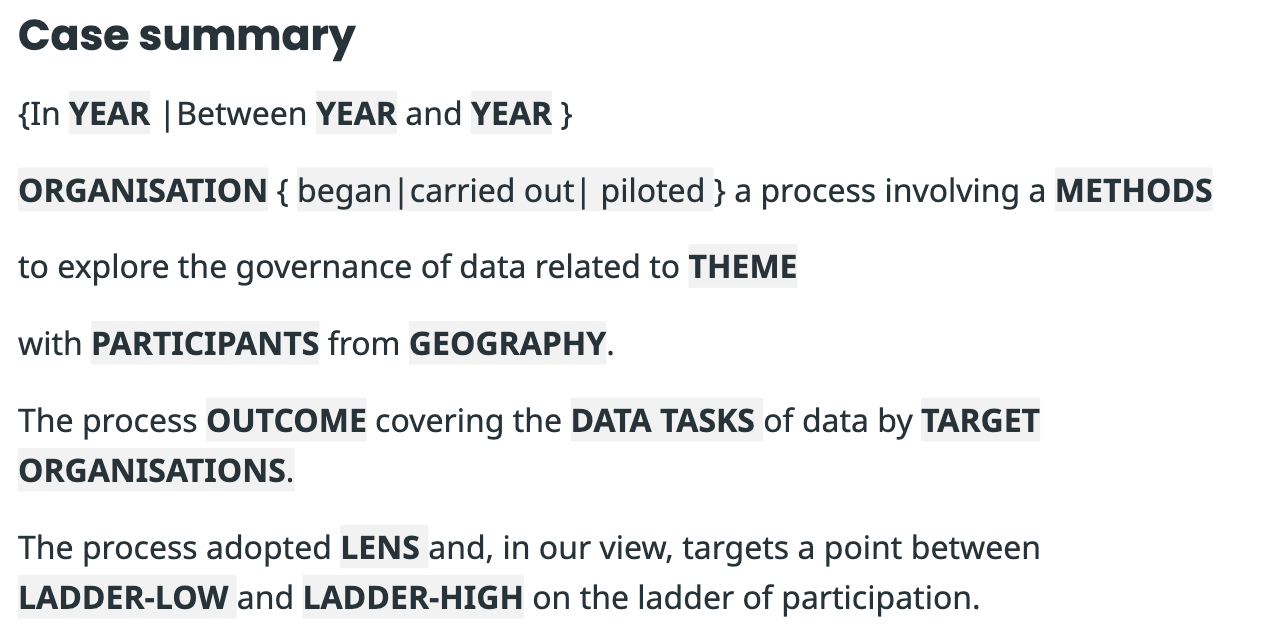

I’ve been starting to reflect on how to present the relationship between different parts of the participatory data governance cases I’ve been gathering. The case study schema has each case with multiple components that feed into each other, so that, for example, a citizens jury case might be broken down into the initial desk review and design, feeding into a set of roundtables that design materials, which are then used by main jury events, and which feed into an analysis process that produces a report. I’ve been thinking about whether it is useful to present this schematically (essentially a graph of the component relationships), and how this might also start to show where the participation process interfaces with organisational decisions. I might manage to get a quick prototype sorted soon.

Other stuff

I’ve also been:

- Preparing an activity to think about our Theory of Change for the team offsite next week;

- Setting up a Zotero group to keep track of Connected by Data literature;

- Working up a session proposal for a roundtable on Collective Data Governance for the 2022 Internet Governance Forum (Nov 28th – 2nd Dec). An open draft of the proposal is here. We have got a good panel coming together – but I’m still looking for potential participants to include who might be thinking about collective data governance from within private sector or governments;

- Starting a first few chats with researchers whose work touches on issues of participatory or collective data governance;

- Submitting our response to the Data Values Project – Reimagining Data and Power Roadmap consultation;

- Doing some preparation for a workshop with the team at Research ICT Africa next week.