[Summary: I promise at some point this blog will carry content other than about incinerators and contracts. But, for the moment one more exciting instalment in the ongoing saga, in which we learn the contracting documents GCC have been fighting to hide show a 30% increase in Javelin Park costs.]

What’s just happened

Gloucestershire County Council (GCC) decided earlier this week to drop their appeal against an ICO ruling that they should release in full a 2015 ‘Value for Money’ analysis carried out just before they signed a revised contact with Urbaser Balfour Beatty (UBB) for building the Javelin Park Incinerator (which we’ve been referring to locally as the Ernst and Young report).

Throughout the process GCC have claimed that ‘commercial’ risk to both the Council and UBB prevents them from disclosing the documents. By dropping the appeal just a month before it was due to go to a Tribunal hearing, they avoid having to prove any of these claims in front of a panel and judge.

In addition, GCC appear to have delayed providing this information in order to commission Ernst and Young to produce another report, this time calculating an assumption-laden average gate fee, in order to continue to make the case for the project. This is at odds with the requirements of the Environmental Information Regulations to prompt disclosure – as presumably GCC must have known the commercial interest were no longer active prior to commissioning this new report, but instead chose to delay disclosure and spend taxpayers money on an ‘explanatory note’.

Where are we now

There’s a lot of history to this story, so to recap quickly.

Gloucestershire County Council have been seeking to build an Energy from Waste Incinerator for over a decade. In 2013 they signed a Public Private Partnership contract with UBB for the project. The contract was signed before planning permission was in place for the construction site. Planning was refused, leading to a two-year delay. This triggered a renegotiation of the contract in 2015, signed in January 2016. The plant is now under construction and close to being operational in 2019. Throughout the process GCC have claimed the project provides savings of up to £150m (later quietly reduced to £100m without explanation) over it’s 25 year life span.

Campaigners have long sought to see the contract, and in early 2016, the Information Rights Tribunal ruled that the majority of details, including gate fees (i.e. the price paid to burn waste) should be disclosed. I then requested a 2015 analysis relating to the re-negotiation, and was only given a highly redacted copy, not showing gate fees. I requested a review, and eventually appealed to the Information Commissioners Office (ICO) against authority refusal to release the information. The ICO ruled that the documents should be disclosed un-redacted. GCC appealed this decision in the summer, and since then have been preparing for a tribunal case claiming that disclosure would be against the contractors and the authorities commercial interest. They have now released the documents, although notably only claiming the contractor no longer has a commercial interest in them being confidential, leaving lingering questions about whether the authority had any legitimate commercial interest in non-disclosure all along.

What do we learn from the new documents

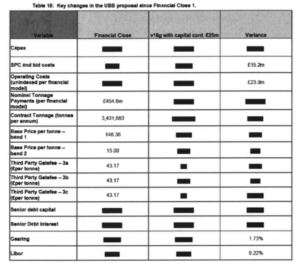

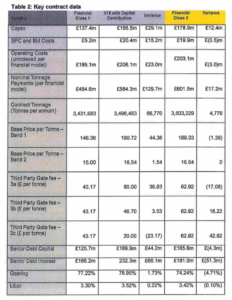

First below is the redacted document from GCC (click for full size). Then there is the equivalent table from the un-redacted and new report by Ernst and Young (which usefully does include the final rather than forecast figures for the renegotiated deal: i.e. the actual new contract numbers assuming there has been no further renegotiation since).

(Note that in the Table 2, the first ‘Variance’ column is between the originally signed contract, and the forecast revisions in 2015, and the second Variance column (in yellow) is between the forecast revisions, and the finally signed updated deal. So to get total variation from 2013 to 2016, you need to add these two columns together.)

So: what can we learn from the new data and documents:

- (1) Firstly, the headline price per-tonne has increased by £42.97/tonne – a staggering 29.3% rise for a three year project delay (cumulative CPI inflation over the same period was 5.13%). The total per-tonne cost for the first 108,000 tonnes is now £189.33/tonne: far above anything any other authority in the country appears to be paying.

- (2) This drives an increase in the nominal tonnage payments over the contract life of £446m to £601.5m. Whilst some of that might be offset by energy income/benefits, given these were also part of the case in 2013, this looks like a massive increase in costs – again just for a three year delay. (Given predicted waste volume rises in all the forecasts the contract is based on, a three year delay also involves starting the project when waste volumes are higher than in 2013 – so some change would be anticipated in this figure even if there was no gate fee increases. But the gate fee increases look like the major component turning Javelin Park from a £450m to a £600m project).

- (3) Other tonnage payments have also increased – although the most notable change between the forecast, and signed renegotiation is that ‘Third Party Gate Fees’ have been kept down – suggesting that the financial modelling for the plant relies on attracting as much additional waste as possible at a low cost, with all the fixed costs of the project subsidised by the taxpayer.

- (4) The Cabinet were told in November 2015 (E&Y VfM report; §3.1) that the capital costs of the project in UBB’s original Revised Project Plan “included a significantly inflated price of £177m.” but that “The council has had some success in negotiating this EPC price down and it now stands at £167m” and “the Council expects to see further improvements in this price”, yet by the signature of the new deal, the capital expenditure costs were also up 30% £178.9m – £2m higher than UBB’s opening gambit!

- (5) The Value for Money calculations (E&Y VfM report, and restated in Table 3, new E&Y report) only carry out comparisons to ‘Termination (Landfill alternative)’ of which at least £60m is the cancellation cost signed up to in 2013. For this reason, the newly released Annex 1 of the report to Cabinet in 2015 (§6) explicitly acknowledges that the most that should be claimed in savings when this is taken out is £93m – and this is only when Council reserves are put into the project. It’s not clear why Cabinet Members continued to use a figure higher than this in public after this report.

- (6) The first important thing from that last point are that at no point in 2015, did the Cabinet carry out a Value for Money assessment comparing the costs of continuing with the 30% more expensive contract, vs. cancelling and re-tendering. Instead, they pressed ahead with a closed-door renegotiation without competitive pressures – which goes a long way to explaining why the contractor could get such a big boost in costs.

- (7) The second thing to note is that the claim of anything close to £100m savings is only secured by the cash injection into the project from reserves. Those are reserves that are then locked up and not available for other use. Without cash injections from reserves, the savings are much lower.

The mystery of the ‘Real Average Gate Fee’

In the new Ernst and Young report that accompanies the response to my EIR/FOI request, a lot is made of a figure called the ‘Real Average Gate Fee’ (RAGF), which is calculated at £112.47/tonne.

Now – a few things about this number:

(1) I googled “Real Average Gate Fee” to see if this was based on an established industry wide methodology. As it turns out – the only place this phrase occurs on the whole of the Internet is in Ernst and Young’s report.

(2) As I understand, this number is based on making best case assumptions about the income to the authority from electricity sales, and third-party income – and assuming the maximum contract tonnages set out in authority forecasts. If those assumptions are not met (e.g. we hit 60% recycling by 2020 and 70% by 2029/30; or waste volumes do not continue to rise as fast as forecast), then, because of the structure of the contract (all front-loaded costs on the first 108,000 tonnes; savings on waste volumes above this), the RAGF would very quickly rise. In other words, the RAGF is only valid if you accept high waste assumptions. In any other scenario it gets much higher.

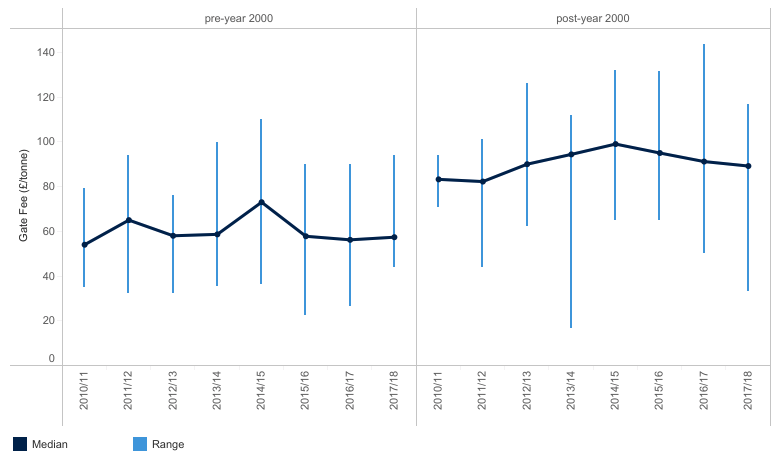

(3) The report compares this to the range of real gate fees that WRAP found in their 2016 survey. Note that WRAP have a pretty robust methodology in their survey, and they state:

“Not all waste management services are costed or charged on a simple gate fee basis (£/tonne). In some cases a tonnage-related payment is just one element of a wider unitary charge paid by an authority” and that “every effort is made to eliminate such responses from the sample”

so the comparison of a constructed ‘Real Average Gate Fee’ from a unitary charge/PPP structure to a real gate fee is questionable at best.

(4) However, even more questionable is picking the 2016 data to compare the RAGF too. We now have 2017 data available from WRAP, and the E&Y report notes that this figure is based on the ‘Net Present Value based date of June 2015‘, so both 2015 and 2017 would seem more reasonable years to compare too.

A quick look at WRAP’s EfW Overview dashboard for post-2000 plants gives us a clue as to why this year was chosen. 2016 is an outlier when it comes to maximum values in WRAPs survey. In 2015, the highest anyone responding to the survey was paying per tonne was £131/tonne, and in 2017 it was £116/tonne.

Even if we allow the not-really-comparable RAGF of £112/tonne – that put it right at the top of the range. Even a small reducting in income from energy, or reductions in waste, would push this into being the most expensive deal in the country.

If you compare the actual gate fee of £190/tonne for the first 108.000 tonnes, it is clear this is massively above what anyone else surveyed is paying.

What we still need to explore

The Ernst and Young Report VfM report notes that the overall lifetime project costs could have been substantially reduced with ‘Prudential Borrowing’ (i.e. relying on low interest loans the authority can achieve, rather than private banks). Annexe 1 to the 2015 Cabinet Report reveals this option was ignored, because it would have required discussion as part of the Council’s budget process in February 2016 and it states “the banks have advised that they need to achieve financial close by the end of the year [2015]”.

However, financial close was not achieved until January 2016 (it seems the banks didn’t mind so much after all?). It’s not yet clear to me what information Councillors outside cabinet had at the time on this decision – and what it tells us about the pursuit of a PFI option, when it appears other, much cheaper public funded options for the project were available.

There is also a question of the missing OJEU (Official Journal of the European Union) notice. It seems that, whilst in most cases, any contract variation of over 10% in value after the Public Contract Regulations 2015 came into force should normally have involved re-tendering, an exception may have been permissable for this project because of ‘unforseen circumstances’ (although whether the planning refusal is something a dilligent authority could not have forseen is open to major question). Notwithstanding that – LGA guidance states that in a case of major contract modification “a special type of notice must be published in OJEU” a “‘Notice of modification of a contract during its term’.”

I’ve not been able to find any evidence that such a notice was issued, and Cllr Rachel Smith has also asked for copies of all OJEU notices related to the project a number of times, and a contract modification notice has never been amongst them.

Where next?

Hopefully a Christmas break! Whilst it was kind of GCC to drop these documents just before Christmas – I’m hoping to have at least a bit of time off.

However, far from proving the value for money or transparency of the project as Councillors claim: these documents show there are still major questions to be answered about how a secret renegotiation led to 30% increase in costs, and why no assessments took place to look at non-landfill alternatives and create at least some sort of competitive pressure at the time of renegotiation.

There are also major questions to be asked about the handing of the Information Tribunal appeal. But those can wait for a day or two at least.