[An occasional weeknotes cross-post from Connected by Data]

At a school governors meeting last week, I was reminded of what, when I first got involved in youth council participation in the late 1990s, we used to talk of as ‘The swimming pool problem’. The conversation that triggered this memory went something like this:

Governor 1: “We need to do something about Parent and Pupil Voice.”

Governor 2: “Well, we often ask the kids what they want in the school. But they always come back asking for a swimming pool: and that’s just impossible.* So not sure it’s worth us spending much time on pupil voice right now.”

*There is literally no space on the school site for a pool, and perhaps more importantly, it would take at least 1000x the available budget.

The idea that, because when asked the open question ‘what do you want to see?’ the people consulted come back with an unrealistic suggestion, is a reason not to engage with participatory practice, is one we often had to fight against as youth councillors. Over time, we learnt that instead of responding to “But we can’t build a swimming pool in every park!” with “Why not?” instead we needed to ask “What did you tell the group about your actual budget? Did you share information about what you do have the power to change?”.

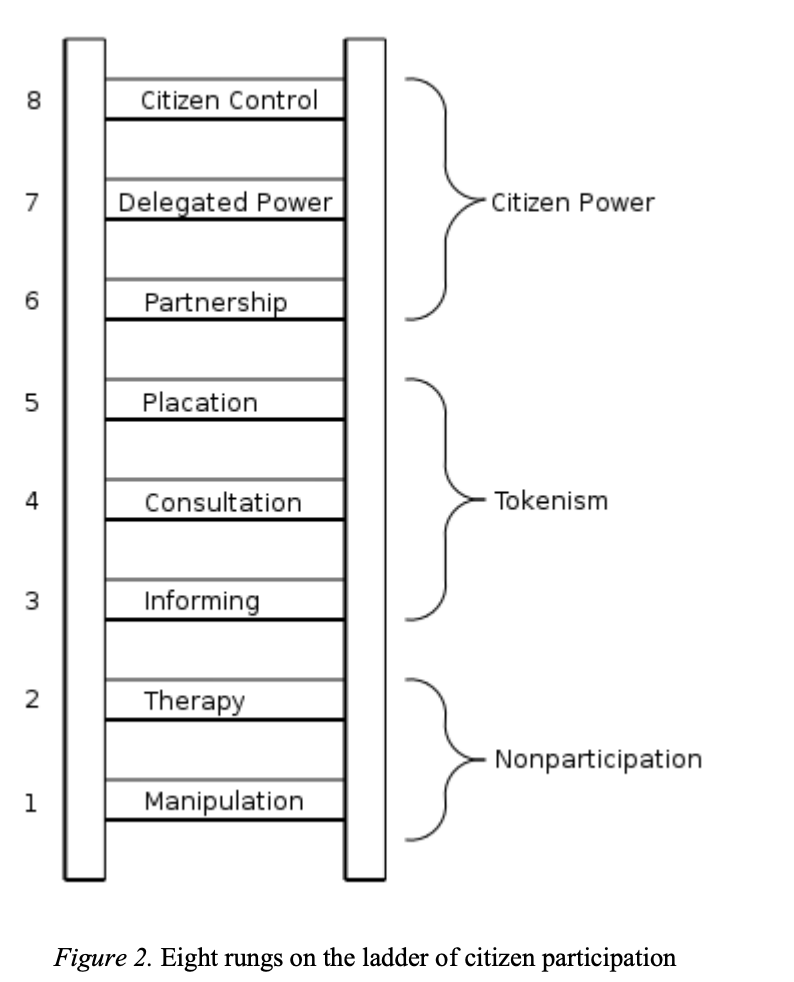

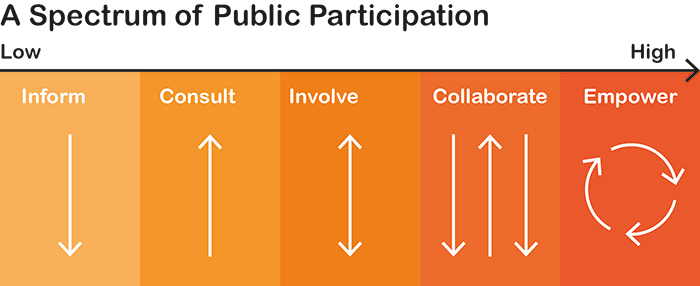

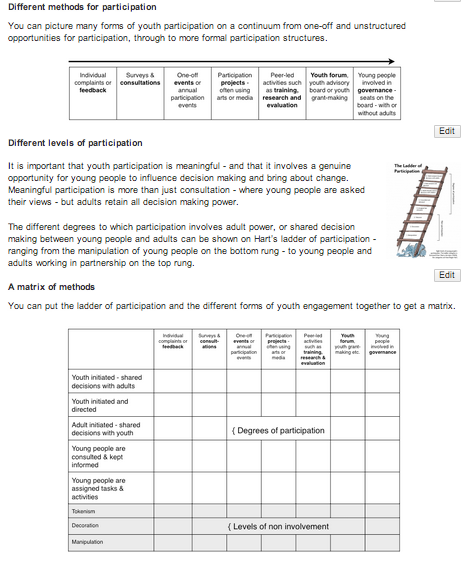

This points to a challenge at the heart of any participatory practice: designing processes that are open enough to allow participants to express views rooted in their authentic experience and interests and that are constrained enough to focus discussions on decisions that can be made, and that give real power and influence to participants.

This theme has come up in three different pieces of work this week.

Firstly, in this write-up of my observations on the NHS AI Lab Public Dialogue on Data Stewardship I discuss an example of public dialogue work that sought to equip participants with background information on a complex topic (use of AI to analyse imaging datasets), and then to scaffold a meaningful discussion about models of data governance to be applied to this.

Secondly, in our evaluation of a deliberative engagement exercise commissioned by Justice Lab (the first Justice Data Matters report) we look at the challenges of supporting a diverse group of members of the public to engage with details of how access to machine-readable data from court records should be governed. In particular, we highlight the value of background materials that can provide shared reference points to enable ‘experts’ and ‘non-experts’ to talk effectively about key concepts like open justice, or kinds of court data use.

Lastly, in this write up describes the ‘Discovery’ workshop we held to inform Joseph Rowntree Foundation’s work on developing an insight infrastructure, we talk about how we used a set of example websites (selected based on prior interviews and survey responses) as the anchor for a discussion about ‘what works’ in provision of insight infrastructure. The JRF team have been keen to avoid imposing too strong a notion of what an insight infrastructure might be at the start of the engagement process, conscious of their power as a funder to (intentionally or not) steer discussions in ways that might prematurely close down important avenues of exploration. However, given the term insight infrastructure is under-defined, we also needed starting points concrete enough to allow comments and ideas raised in the workshop to speak to the kinds of programmes or activities JRF might develop.

In reflecting on the development of public dialogue and deliberative workshop approaches over the last few decades, it is good to see that a lot of participation has moved on from simply asking (and then dismissing the answer to) the question: “So what do you want?”. However, I’m also left observing that the seemingly ‘intangibility’ of so many data questions, and the way they are often interrelated with other complex questions (open justice; health economics; the politics of poverty etc.) means that developing materials and methods that will enable both inclusive and powerful citizen voice on data governance is an ongoing challenge.

In other news

Tickets are now available for Gloucestershire Data Day on 26th April – the event I’ve been co-organising with Create Gloucestershire, Active Gloucestershire and Barnwood Trust. It’s shaping up into a great agenda to mix practical and critical conversations on the role of data in community action.

Plus, we’ve got a lovely logo designed by the fantastic Joe Magee, who is more usually found creating films and backdrops for Bill Bailey tours: setting the creative bar high for the day.