[Summary: An extended write-up of a tweet-length critique]

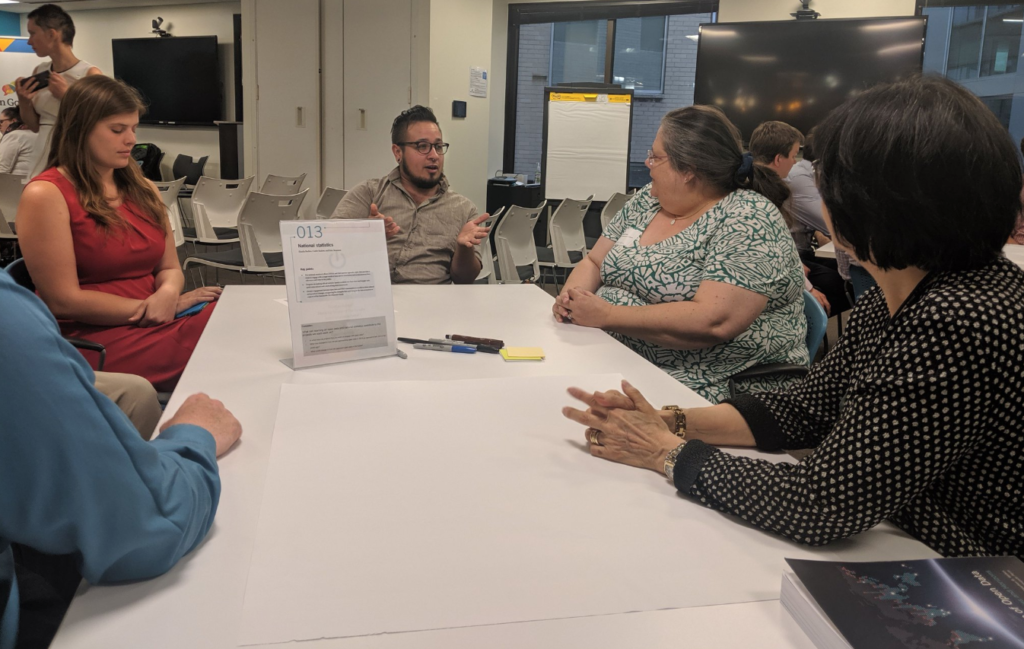

The Open Government Partnership (OGP) Summit is, on many levels, an inspiring event. Civil society and government in dialogue together on substantive initiatives to improve governance, address civic engagement, and push forward transparency and accountability reforms. I’ve had the privilege, through various projects, to be a civil society participant in each of the 6 summits in Brasilia, London, Mexico, Paris, Tbilisi and now Ottawa. I have a lot of respect for the OGP Support Unit team, and the many government and civil society participants who work to make OGP a meaningful forum and mechanism for change. And I recognise that the substance of a summit is often found in the smaller sessions, rather than the set-piece plenaries. But, the summit’s opening plenary offered a powerful example of the way in which a continued embrace of a tech-goggles approach at OGP, and weaknesses in the design of the partnership and it’s events, misdirect attention, and leave some of the biggest open government challenges unresolved.

Trudeau’s Tech Goggles?

We need to call out the techno-elitism, and political misdirection, that mean the Prime Minister of Canada can spend the opening plenary in an interview that focussed more on regulation of Facebook, than on regulation of the money flowing into politics; and more time answering questions about his Netflix watching, than discussing the fact that millions of people still lack the connectivity, social capital or civic space to engage in any meaningful form of democratic decision making. Whilst (new-)media inevitably plays a role in shaping patterns of populism, a narrow focus on the regulation of online platforms directs attention away from the ways in which economic forces, transportation policy, and a relentless functionalist focus on ‘efficient’ public services, without recognising their vital role in producing social-solidarity, has contributed to the social dislocation in which populism (and fascism) finds root.

Of course, the regulation of large technology firms matters, but it’s ultimately an implementation detail that some come as part of wider reforms to our democratic systems. The OGP should not be seeking to become the Internet Governance Forum (and if it does want to talk tech regulation, then it should start by learning lessons from the IGFs successes and failures), but should instead be looking deeper at the root causes of closing civic space, and of the upswing of populist, non-participatory, and non-inclusive politics.

Beyond the ballot box?

The first edition of the OGP’s Global Report is sub-titled ‘Democracy Beyond the Ballot Box’ and opens with the claim that:

…authoritarianism is on the rise again. The current wave is different–it is more gradual and less direct than in past eras. Today, challenges to democracy come less frequently from vote theft or military coups; they come from persistent threats to activists and journalists, the media, and the rule of law.

The threats to democracy are coming from outside of the electoral process and our response must be found there too. Both the problem and the solution lie “beyond the ballot box.”

There appears to be a non-sequitur here. That votes are not being stolen through physical coercion, does not mean that we should immediately move our focus beyond electoral processes. Much like the Internet adage that ‘censorship is damage, route around it’, there can be a tendency in Open Government circles to treat the messy politics of governing as a fundamentally broken part of government, and to try and create alternative systems of participation or engagement that seek to be ‘beyond politics’. Yet, if new systems of participation come to have meaningful influence, what reason do we have to think they won’t become subject to the legitimate and illegitimate pressures that lead to deadlock or ‘inefficiency’ in our existing institutions? And as I know from local experience, citizen scrutiny of procurement or public sending from outside government can only get us so far without political representatives willing to use and defend they constitutional powers of scrutiny.

I’m more and more convinced that to fight back against closing civic space and authoritarian government, we cannot work around the edges: but need to think more deeply about about how we work to get capable and ethical politicians elected: held in check by functioning party systems, and engaging in fair electoral competition overseen by robust electoral institutions. We need to go back to the ballot box, rather than beyond it. Otherwise we are simply ceding ground to the forces who have progressively learnt to manipulate elections, without needing to directly buy votes.

Globally leaders, locally laggards?

The opening plenary also featured UK Government Minister John Penrose MP. But, rather than making even passing mention of the UK’s OGP National Action Plan, launched just one day before, Mr Penrose talked about UK support for global beneficial ownership transparency. Now: it is absolutely great that that ideas of beneficial ownership transparency are gaining pace through the OGP process.

But, there is a design flaw in a multi-stakeholder partnership where a national politician of a member country is able to take the stage without any response from civil society. And where there is no space for questions on the fact that the UK government has delayed the extension of public beneficial ownership registries to UK Overseas Territories until at least 2023. The misdirection, and #OpenWashing at work here needs to be addressed head on: demanding honest reflections from a government minister on the legislative and constitutional challenges of extending beneficial ownership transparency to tax havens and secrecy jurisdictions.

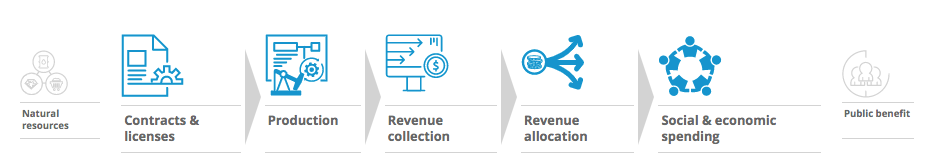

As long as politicians and presenters are not challenged when framing reforms as simple (and cheap) technological fixes, we will cease to learn about and discuss the deeper legal reforms needed, and the work needed on implementation. As our State of Open Data session on Friday explored: data and standards must be the means not the ends, and more public scepticism about techno-determinist presentations would be well warranted.

Back, however, to event design. Although when hosted in London, the OGP Summit offered UK civil society at least, an action-forcing moment to push forward substantive National Action Plan commitments, the continued disappearance of performative spaces in which governments account for their NAPs, or different stakeholders from a countries multi-stakeholder group share the stage, means that (wealthy, and northern) governments are put in control of the spin.

Grounds for hope?

It’s clear that very many of us understand that open government ≠ technology, at least if (irony noted) likes and RTs on the below give a clue.

#ogpCanada Can we just agree that Open Gov ≠ Technology once and for all. This is the OGP Summit – not the Internet Governance Forum. Let’s talk about regulation of money in politics & creating democratic and civic space. Treat the technical platforms as implementation detail.

— Tim Davies (@timdavies) May 29, 2019

But we need to hone our critical instincts to apply that understanding to more of the discussions in fora like OGP. And if, as the Canadian Co-Chair argued in closing, “OGP is developing a new forms of multilateralism”, civil society needs to be much more assertive in taking control of the institutional and event design of OGP Summits, to avoid this being simply a useful annual networking shin-dig. The closing plenary also included calls to take seriously threats to civic space: but how can we make sure we’re not just saying this from the stage in the closing, but that the institutional design ensures there are mechanisms for civil society to push forward action on this issue.

In looking to the future of OGP, we should consider how civil society spends some time taking technology off the table. Let it emerge as an implementation detail, but perhaps let’s see where we get when we don’t let techo-discussions lead?