[Summary: rapid reflections on applying extractives metaphors to data in a international development context]

In yesterday’s Data as Development Workshop at the Belfer Center for Science and International Affairs we were exploring the impact of digital transformation on developing countries and the role of public policy in harnessing it. The role of large tech firms (whether from Silicon Valley, or indeed from China, India and other countries around the world) was never far from the debate.

Although in general I’m not a fan of descriptions of ‘data as the new oil’ (I find the equation tends to be made as part of rather breathless techno-deterministic accounts of the future), an extractives metaphor may turn out to be quite useful in asking about the kinds of regulatory regimes that could be appropriate to promote both development, and manage risks, from the rise of data-intensive activity in developing countries.

Over recent decades, principles of extractives governance have developed that recognise the mineral and hydrocarbon resources of a country as at least partially part of the common wealth, such that control of extraction should be regulated, firms involved in extraction should take responsibility for externalities from their work, revenues should be taxed, and taxes invested into development. When we think about firms ‘extracting’ data from a country, perhaps through providing social media platforms and gathering digital trace data, or capturing and processing data from sensor networks, or even collecting genomic information from a biodiverse area to feed into research and product development, what regimes could or should exist to make sure benefits are shared, externalities managed, and the ‘common wealth’ that comes from the collected data, does not entirely flow out of the country, or into the pockets of a small elite?

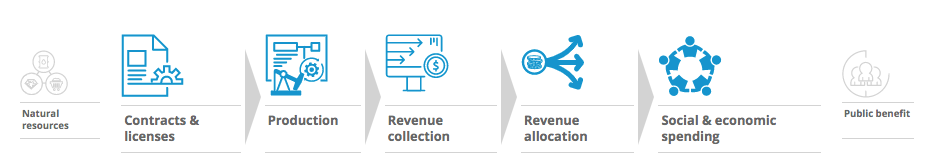

Although real world extractives governance has often not resolved all these questions successfully, one tool in the governance toolbox has been the Extractives Industry Transparency Initiative (EITI) . Under EITI, member countries and companies are required to disclose information on all stages of of the extractives process: from the granting of permissions to operate, through to the taxation or revenue sharing secured, and the social and economic spending that results. The model recognises that governance failures might come from the actions of both companies, and governments – rather than assuming one or the other is the problem or benign. Although transparency alone does not solve governance problems: it can support better debate about both policy design and implementation, and can help address distorting information and power asymmetries that otherwise work against development.

So, what could an analogous initiative look like if applied to international firms involved in ‘data extraction’?

(Note: this is a rough-and-ready thought experiment testing out an extended version of an originally tweet-length thought. It is not a fully developed argument in favour of the ideas explored here).

Data as a national resource

Before conceptualising a ‘data extraction transparency initiative’ we need to first think about what counts as ‘data extraction’. This involves considering the collected informational (and attention) resources of a population as a whole. Although data itself can be replicated (marking a key difference from finite fossil fuels and mineral resources), the generation and use of data is often rival (i.e. if I spend my time on Facebook, I’m not spending it on some other platform, and/or, some other tasks and activities), involves first mover advantages (e.g. the first person who street view maps country X may corner the market), and can be made finite through law (e.g. someone collecting genomic material from a country may gain intellectual property rights protection for their data), or simply through restricting access (e.g. as Jeni considers here, where data is gathered from a community and used to shape policy, without the data being shared back to that community).

We could think then of data extraction as any data collection process which ‘uses up’ a common resource such as attention and time, which reduces the competitiveness of a market (thus shifting consumer to producer surplus), or which reduces the potential extent of the knowledge commons through intellectual property regimes or other restrictions on access and use. Of course, the use of an extracted data resource may have economic and social benefits that feed back to the subjects of the extraction. The point is not that all extraction is bad, but is rather to be aware that data collection and use as an embedded process is definitely not the non-rival, infinitely replicable and zero-cost activity that some economic theories would have us believe.

(Note that underlying this lens is the idea that we should approach data extraction at the level of populations and environments, rather than trying to conceptualise individual ownership of data, and to define extraction in terms of a set of distinct transactions between firms and individuals.)

Past precedent: states and companies

Our model then for data extraction involves a relationship between firms and communities, which we will assume for the moment can be adequately represented by their states. A ‘data extractive transparency initiative’ would then be asking for disclosure from these firms at a country-by-country level, and disclosure from the states themselves. Is this reasonable to expect?

We can find some precedents for disclosure by looking at the most recent Ranking Digital Rights Report, released last week. This describes how many firms are now providing data about government requests for content or account restriction. A number of companies produce detailed transparency reports that describe content removal requests from government, or show political advertising spend. This at least establishes the idea that voluntarily, or through regulation, it is feasible to expect firms to disclose certain aspects of their operations.

The idea that states should disclose information about their relationship with firms is also reasonably well established (if not wholly widespread). Open Contracting, and the kind of project-level disclosure of payments to government that can be see at ResourceProjects.org illustrate ways in which transparency can be brought to the government-private sector nexus.

In short, encouraging or mandating the kinds of disclosures we might consider below is not a new. Targeted transparency has long been in the regulatory toolbox.

Components of transparency

So – to continue the thought experiment: if we take some of the categories of EITI disclosure, what could this look like in a data context?

Legal framework

Countries would publish in a clear, accessible (and machine-readable?) form, details of the legal frameworks relating to privacy and data protection, intellectual property rights, and taxation of digital industries.

This should help firms to understand their legal obligations in each country, and may also make it easier for smaller firms to provide responsible services across borders without current high costs of finding the basic information needed to make sure they are complying with laws country-by-country.

Firms could also be mandated to make their policies and procedures for data handling clear, accessible (and machine-readable?).

Contracts, licenses and ownership

Whenever governments sign contracts that allow private sector to collect or control data about citizens, public spaces, or the environment, these contracts should be public.

(In the Data as Development workshop, Sriganesh related the case of a city that had signed a 20 year deal for broadband provision, signing over all sorts of data to the private firm involved.)

Similarly, licenses to operate, and permissions granted to firms should be clearly and publicly documented.

Recently, EITI has also focussed on beneficial ownership information: seeking to make clear who is really behind companies. For digital industries, mandating clear disclosure of corporate structure, and potentially also of the data-sharing relationships between firms (as GDPR starts to establish) could allow greater scrutiny of who is ultimately benefiting from data extraction.

Production

In the oil, gas and mining context, firms are asked to reveal production volumes (i.e. the amount extracted). The rise of country-by-country reporting, and project-level disclosure has sought to push for information on activity to be revealed not at the aggregated firm level, but in a more granular way.

For data firms, this requirement might translate into disclosure of the quantity of data (in terms of number of users, number of sensors etc.) collected from a country, or disclosure of country by country earnings.

Revenue collection

One important aspect of EITI has been an audit and reconciliation process that checks that the amounts firms claim to be paying in taxes or royalties to government match up with the amounts government claims to have received. This requires disclosure from both private firms and government.

A better understanding of whose digital activities are being taxed, and how, may support design of better policy that allows a share of revenues from data extraction to flow to the populations whose data-related resources are being exploited.

In yesterday’s workshop, Sriganesh pointed to the way in which some developing country governments now treat telecoms firms as an easy tax collection mechanism: if everyone wants a mobile phone connection, and mobile providers are already collecting payments, levying a charge on each connection, or a monthly tax, can be easy to administer. But, in the wrong places, and at the wrong levels, such taxes may capture consumer rather than producer surplus, and suppress rather than support the digital economy,

Perhaps one of the big challenges for ‘data as development’ when companies in more developed economies may extract data from developing countries, but process it back ‘at home’, is that current economic models may suggest that the biggest ‘added value’ is generated from the application of algorithms and processing. This (combined with creative accounting by big firms) can lead to little tax revenue in the countries from which data was originally extracted. Combining ‘production’ and ‘revenue’ data can at least bring this problem into view more clearly – and a strong country-by-country reporting regime may even allow governments to more accurately apply taxes.

Revenue allocation, social and economic spending

Important to the EITI model, is the idea that when governments do tax, or collect royalties, they do so on behalf of the whole polity, and they should be accountable for how they are then using the resulting resources.

By analogy, a ‘data extraction transparency initiative’ initiative may include requirements for greater transparency about how telecoms and data taxes are being used. This could further support multi-stakeholder dialogue on the kinds of public sector investments needed to support national development through use of data resources.

Environmental and social reporting

EITI encourages countries to ‘go beyond the standard’ and disclose other information too, including environmental information and information on gender.

Similar disclosures could also form part of a ‘data extraction transparency initiative’: encouraging or requiring firms to provide information on gender pay gaps and their environmental impact.

Is implementation possible?

So far this though experiment has established ways of thinking about ‘data extraction’ by analogy to natural resource extraction, and has identified some potential disclosures that could be made by both governments and private actors. It has done so in the context of thinking about sustainable development, and how to protect developing countries from data-exploitation, whilst also supporting them to appropriately and responsibly harness data as a developmental tool. There are some rough edges in all this: but also, I would argue, some quite feasible proposals too (disclosure of data-related contracts for example).

Large scale implementation would, of course, need careful design. The market structure, capital requirements and scale of digital and data firms is quite different to that of the natural resource industry. Compliance costs of any disclosure regime would need to be low enough to ensure that it is not only the biggest firms that can engage. Developing country governments also often have limited capacity when it comes to information management. Yet, most of the disclosures envisaged above relate to transactions that, if ‘born digital’, should be fairly easy to publish data on. And where additional machine-readable data (e.g. on laws and policies) is requested, if standards are designed well, there could be a win-win for firms and governments – for example, by allowing firms to more easily identify and select cloud providers that allow them to comply with the regulatory requirements of a particular country.

The political dimensions of implementation are, of course, another story – and one I’ll leave out of this thought experiment for now.

But why? What could the impact be?

Now we come to the real question. Even if we could create a ‘data extraction transparency initiative’, could it have any meaningful developmental impacts?

Here’s where some of the impacts could lie:

- If firms had to report more clearly on the amount of ‘data’ they are taking out of a country, and the revenue that gives rise to, governments could tailor licensing and taxation regimes to promote more developmental uses of data. Firms would also be encouraged think about how they are investing in value-generation in countries where they operate.

- If contracts that involve data extraction are made public, terms that promote development can be encouraged, and those that diminish the opportunity to national development can be challenged.

- If a country government chooses to engage in forms of ‘digital protectionism’, or to impose ‘local content requirements’ on the development of data technologies that could bring long-term benefits, but risk creating a short-term hit on the quality of digital services available in a country, greater transparency could support better policy debate. (Noting, however, that recent years have shown us that politics often trumps rational policy making in the real world).

There will inevitably be readers who see the thrust of this thought experiment as fundamentally anti-market, and who are fearful of, or ideologically opposed, to any of the kinds of government intervention that increasing transparency around data extraction might bring. It can be hard to imagine a digital future not dominated by the ever-increased rise of a small number of digital monopolies. But, from a sustainable development point of view, allowing another path to be sought: which supports to creation of resilient domestic technology industries, which prices in positive and negative externalities from data extraction, and which therefore allows active choices to be made about how national data resources are used as common asset, may be no bad thing.

[Summary: blogging the

[Summary: blogging the