[Summary: Slides, notes and references from a conference talk in Plymouth]

Update – April 2020: A book chapter based on this blog post is now published as “Shaping participatory public data infrastructure in the smart city: open data standards and the turn to transparency” in The Routledge Companion to Smart Cities.

Original blog post version below:

A few months back I was invited to give a presentation to a joint plenary of the ‘Whose Right to the Smart City‘ and ‘DataAche 2017‘ conferences in Plymouth. Building on some recent conversations with Jonathan Gray, I took the opportunity to try and explore some ideas around the concept of ‘participatory data infrastructure’, linking those loosely with the smart cities theme.

As I fear I might not get time to turn it into a reasonable paper anytime soon, below is a rough transcript of what I planned to say when I presented earlier today. The slides are also below.

For those at the talk, the promised references are found at the end of this post.

Thanks to Satyarupa Shekar for the original invite, Katharine Willis and the Whose Right to the Smart Cities network for stimulating discussions today, and to the many folk whose ideas I’ve tried to draw on below.

Participatory public data infrastructure: open data standards and the turn to transparency

In this talk, my goal is to explore one potential strategy for re-asserting the role of citizens within the smart-city. This strategy harnesses the political narrative of transparency and explores how it can be used to open up a two-way communication channel between citizens, states and private providers.

This not only offers the opportunity to make processes of governance more visible and open to scrutiny, but it also creates a space for debate over the collection, management and use of data within governance, giving citizens an opportunity to shape the data infrastructures that do so much to shape the operation of smart cities, and of modern data-driven policy and it’s implementation.

In particular, I will focus on data standards, or more precisely, open data standards, as a tool that can be deployed by citizens (and, we must acknowledge, by other actors, each with their own, sometimes quite contrary interests), to help shape data infrastructures.

Let me set out the structure of what follows. It will be an exploration in five parts, the first three unpacking the title, and then the fourth looking at a number of case studies, before a final section summing up.

- Participatory public data infrastructure

- Transparency

- Standards

- Examples: Money, earth & air

- Recap

Part 1: Participatory public data infrastructure

Data infrastructure

infrastructure. /?nfr?str?kt??/ noun. “the basic physical and organizational structures and facilities (e.g. buildings, roads, power supplies) needed for the operation of a society or enterprise.” 1

The word infrastructure comes from the latin ‘infra-‘ for below, and structure, meaning structure. It provides the shared set of physical and organizational arrangements upon which everyday life is built.

The notion of infrastructure is central to conventional imaginations of the smart city. Fibre-optic cables, wireless access points, cameras, control systems, and sensors embedded in just about anything, constitute the digital infrastructure that feed into new, more automated, organizational processes. These in turn direct the operation of existing physical infrastructures for transportation, the distribution of water and power, and the provision of city services.

However, between the physical and the organizational lies another form of infrastructure: data and information infrastructure.

(As a sidebar: Although data and information should be treated as analytically distinct concepts, as the boundary between the two concepts is often blurred in the literature, including in discussions of ‘information infrastructures’, and as information is at times used as a super-category including data, I won’t be too strict in my use of the terms in the following).

(That said,) It is by being rendered as structured data that the information from the myriad sensors of the smart city, or the submissions by hundreds of citizens through reporting portals, are turned into management information, and fed into human or machine based decision-making, and back into the actions of actuators within the city.

Seen as a set of physical or digital artifacts, the data infrastructure involves ETL (Extract, Transform, Load) processes, APIs (Application Programming Interfaces), databases and data warehouses, stored queries and dashboards, schema, codelists and standards. Seen as part of a wider ‘data assemblage’ (Kitchin 5) this data infrastructure also involves various processes of data entry and management, of design, analysis and use, as well relationships to other external datasets, systems and standards.

However, if is often very hard to ‘see’ data infrastructure. By their very natures, infrastructures moves into the background, often only ‘visible upon breakdown’ to use Star and Ruhleder’s phrase 2. (For example, you may only really pay attention to the shape and structure of the road network when your planned route is blocked…). It takes a process of “infrastructural inversion” to bring information infrastructures into view 3, deliberately foregrounding the background. I will argue shortly that ‘transparency’ as a policy performs much the same function as ‘breakdown’ in making the contours infrastructure more visible: taking something created with one set of use-cases in mind, and placing it in front of a range of alternative use-cases, such that its affordances and limitations can be more fully scrutinized, and building on that scrutiny, it’s future development shaped. But before we come to that, we need to understand the extent of ‘public data infrastructure’ and the different ways in which we might understand a ‘participatory public data infrastructure’.

Public data infrastructure

There can be public data without a coherent public data infrastructure. In ‘The Responsive City’ Goldsmith and Crawford describe the status quo for many as “The century-old framework of local government – centralized, compartmentalized bureaucracies that jealously guard information…” 4. Datasets may exist, but are disconnected. Extracts of data may even have come to be published online in data portals in response to transparency edicts – but it exists as islands of data, published in different formats and structures, without any attention to interoperability.

Against this background, initiatives to construct public data infrastructure have sought to introduce shared technology, standards and practices that provide access to a more coherent collection of data generated by, and focusing on, the public tasks of government.

For example, in 2012, Denmark launched their ‘Basic Data’ programme, looking to consolidate the management of geographic, address, property and business data across government, and to provide common approaches to data management, update and distribution 6. In the European Union, the INSPIRE Directive and programme has been driving creation of a shared ‘Spatial Data Infrastructure’ since 2007, providing reference frameworks, interoperability rules, and data sharing processes. And more recently, the UK Government has launched a ‘Registers programme’ 8 to create centralized reference lists and identifiers of everything from countries to government departments, framed as part of building governments digital infrastructure. In cities, similar processes of infrastructure building, around shared services, systems and standards are taking place.

The creation of these data infrastructures can clearly have significant benefits for both citizens and government. For example, instead of citizens having to share the same information with multiple services, often in subtly different ways, through a functioning data infrastructure governments can pick up and share information between services, and can provide a more joined up experience of interacting with the state. By sharing common codelists, registers and datasets, agencies can end duplication of effort, and increase their intelligence, drawing more effectively on the data that the state has collected.

However, at the same time, these data infrastructures tend to have a particularly centralizing effect. Whereas a single agency maintaining their own dataset has the freedom to add in data fields, or to restructure their working processes, in order to meet a particular local need – when that data is managed as part of a centralized infrastructure, their ability to influence change in the way data is managed will be constrained both by the technical design and the institutional and funding arrangements of the data infrastructure. A more responsive government is not only about better intelligence at the center, it is also about autonomy at the edges, and this is something that data infrastructures need to be explicitly designed to enable, and something that they are generally not oriented towards.

In “Roads to Power: Britain Invents the Infrastructure State” 10, Jo Guldi uses a powerful case study of the development of the national highways networks to illustrate the way in which the design of infrastructures shapes society, and to explore the forces at play in shaping public infrastructure. When metaled roads first spread out across the country in the eighteenth century, there were debates over whether to use local materials, easy to maintain with local knowledge, or to apply a centralized ‘tarmacadam’ standard to all roads. There were questions of how the network should balance the needs of the majority, with road access for those on the fringes of the Kingdom, and how the infrastructure should be funded. This public infrastructure was highly contested, and the choices made over it’s design had profound social consequences. Jo uses this as an analogy for debates over modern Internet infrastructures, but it can be equally applied to explore questions around an equally intangible public data infrastructure.

If you build roads to connect the largest cities, but leave out a smaller town, the relative access of people in that town to services, trade and wider society is diminished. In the same way, if your data infrastructure lack the categories to describe the needs of a particular population, their needs are less likely to be met. Yet, that town connected might also not want to be connected directly to the road network, and to see it’s uniqueness and character eroded; much like some groups may also want to resist their categorization and integration in the data infrastructure in ways that restrict their ability to self-define and develop autonomous solutions, in the face of centralized data systems that are necessarily reductive.

Alongside this tension between centralization and decentralization in data infrastructures, I also want to draw attention to another important aspect of public data infrastructures. That is the issue of ownership and access. Increasingly public data infrastructures may rely upon stocks and flows of data that are not publicly owned. In the United Kingdom, for example, the Postal Address File, which is the basis of any addressing service, was one of the assets transferred to the private sector when Royal Mail was sold off. The Ordnance Survey retains ownership and management of the Unique Property Reference Number (UPRN), a central part of the data infrastructure for local public service delivery, yet access to this is heavily restricted, and complex agreements govern the ability of even the public sector to use it. Historically, authorities have faced major challenges in relation to ‘derived data’ from Ordnance Survey datasets, where the use of proprietary mapping products as a base layer when generating local records ‘infects’ those local datasets with intellectual property rights of the proprietary dataset, and restricts who they can be shared with. Whilst open data advocacy has secured substantially increased access to many publicly owned datasets in recent years, when the datasets the state is using are privately owned in the first place, and only licensed to the state, the potential scope for public re-use and scrutiny of the data, and scrutiny of the policy made on the basis of it, is substantially limited.

In the case of smart cities, I suspect this concern is likely to be particularly significant. Take transit data for example: in 2015 Boston, Massachusetts did a deal with Uber to allow access to data from the data-rich transportation firm to support urban planning and to identify approaches to regulation. Whilst the data shared reveals something of travel times, the limited granularity rendered it practically useless for planning purposes, and Boston turned to senate regulations to try and secure improved data 9. Yet, even if the city does get improved access to data about movements via Uber and Lyft in the city – the ability of citizens to get involved in the conversations about policy from that data may be substantially limited by continued access restrictions on the data.

With the Smart City model often involving the introduction of privately owned sensors networks and processes, the extent to which the ‘data infrastructure for public tasks ceases to have the properties that we will shortly see are essential to a ‘participatory public data infrastructure’ is a question worth paying attention to.

Participatory public data infrastructure

I will posit then that the grown of public data infrastructures is almost inevitable. But the shape they take is not. I want, in particular then, to examine what it would mean to have a participatory public data infrastructure.

I owe the concept of a ‘participatory public data infrastructure’ in particular to Jonathan Gray ([11], [12], [13]), who has, across a number of collaborative projects, sought to unpack questions of how data is collected and structured, as well as released as open data. In thinking about the participation of citizens in public data, we might look at three aspects:

- Participation in data use

- Participation in data production

- Participation in data design

And, seeing these as different in kind, rather than different in degree, we might for each one deploy Arnstein’s ladder of participation [14] as an analytical tool, to understand that the extent of participation can range from tokenism through to full shared decision making. As for all participation projects, we must also ask the vitally important question of ‘who is participating?’.

At the bottom-level ‘non-participation’ runs of Arnstein’s ladder we could see a data infrastructure that captures data ‘about’ citizens, without their active consent or involvement, that excludes them from access to the data itself, and then uses the data to set rules, ‘deliver’ services, and enact policies over which citizens have no influence in either their design of delivery. The citizen is treated as an object, not an agent, within the data infrastructure. For some citizens contemporary experience, and in some smart city visions, this description might not be far from a direct fit.

By contrast, when citizens have participation in the use of a data infrastructure they are able to make use of public data to engage in both service delivery and policy influence. This has been where much of the early civic open data movement placed their focus, drawing on ideas of co-production, and government-as-a-platform, to enable partnerships or citizen-controlled initiatives, using data to develop innovative solutions to local issues. In a more political sense, participation in data use can remove information inequality between policy makers and the subjects of that policy, equalizing at least some of the power dynamic when it comes to debating policy. If the ‘facts’ of population distribution and movement, electricity use, water connections, sanitation services and funding availability are shared, such that policy maker and citizen are working from the same data, then the data infrastructure can act as an enabler of more meaningful participation.

In my experience though, the more common outcome when engaging diverse groups in the use of data, is not an immediate shared analysis – but instead of a lot of discussion of gaps and issues in the data itself. In some cases, the way data is being used might be uncontested, but the input might turn out to be misrepresenting the lived reality of citizens. This takes us to the second area of participation: the ability to not jusT take from a dataset, but also to participate in dataset production. Simply having data collected from citizens does not make a data infrastructure participatory. That sensors tracked my movement around an urban area, does not make me an active participant in collecting data. But by contrast, when citizens come together to collect new datasets, such as the water and air quality datasets generated by sensors from Public Lab 15, and are able to feed this into the shared corpus of data used by the state, there is much more genuine participation taking place. Similarly, the use of voluntary contributed data on Open Street Map, or submissions to issue-tracking platforms like FixMyStreet, constitute a degree of participation in producing a public data infrastructure when the state also participates in use of those platforms.

It is worth noting, however, that most participatory citizen data projects, whether concerned with data use of production, are both patchy in their coverage, and hard to sustain. They tend to offer an add-on to the public data infrastructure, but to leave the core substantially untouched, not least because of the significant biases that can occur due to inequalities of time, hardware and skills to be able to contribute and take part.

If then we want to explore participation that can have a sustainable impact on policy, we need to look at shaping the core public data infrastructure itself – looking at the existing data collection activities that create it, and exploring whether or not the data collected, and how it is encoded, serves the broad public interest, and allows the maximum range of democratic freedom in policy making and implementation. This is where we can look at a participatory data infrastructure as one that enables citizens (and groups working on their behalf) to engage in discussions over data design.

The idea that communities, and citizens, should be involved in the design of infrastructures is not a new one. In fact, the history of public statistics and data owes a lot to voluntary social reform focused on health and social welfare collecting social survey data in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries to influence policy, and then advocating for government to take up ongoing data collection. The design of the census and other government surveys have long been sources of political contention. Yet, with the vast expansion of connected data infrastructures, which rapidly become embedded, brittle and hard to change, we are facing a particular moment at which increased attention is needed to the participatory shaping of public data infrastructures, and to considering the consequences of seemingly technical choices on our societies in the future.

Ribes and Baker [16], in writing about the participation of social scientists in shaping research data infrastructures draw attention to the aspect of timing: highlighting the limited window during which an infrastructure may be flexible enough to allow substantial insights from social science to be integrated into its development. My central argument is that transparency, and the move towards open data, offers a key window within which to shape data infrastructures.

Part 2: Transparency

transparency /tran?spar(?)nsi/ noun “the quality of being done in an open way without secrets” 21

Advocacy for open data has many distinct roots: not only in transparency. Indeed, I’ve argued elsewhere that it is the confluence of many different agendas around a limited consensus point in the Open Definition that allowed the breakthrough of an open data movement late in the last decade [17] [18]. However, the normative idea of transparency plays an important roles in questions of access to public data. It was a central part of the framing of Obama’s famous ‘Open Government Directive’ in 2009 20, and transparency was core to the rhetoric around the launch of data.gov.uk in the wake of a major political expenses scandal.

Transparency is tightly coupled with the concept of accountability. When we talk about government transparency, it is generally as part of government giving account for it’s actions: whether to individuals, or to the population at large via the third and fourth estates. To give effective account means it can’t just make claims, it has to substantiate them. Transparency is a tool allowing citizens to exercise control over their governments.

Sweden’s Freedom of the Press law from 1766 were the first to establish a legal right to information, but it was a slow burn until the middle of the last century, when ‘right to know’ statutes started to gather pace such that over 100 countries now have Right to Information laws in place. Increasingly, these laws recognize that transparency requires not only access to documents, but also access to datasets.

It is also worth noting that transparency has become an important regulatory tool of government: where government may demand transparency off others. As Fung et. al argue in ‘Full Disclosure’, governments have turned to targeted transparency as a way of requiring that certain information (including from the private sector) is placed in the public domain, with the goal of disciplining markets or influencing the operation of marketized public services, by improving the availability of information upon which citizens will make choices [19].

The most important thing to note here is that demands for transparency are often not just about ‘opening up’ a dataset that already exists – but ultimately are about developing an account of some aspect of public policy. To create this account might require data to be connected up from different silos, and may required the creation of new data infrastructures.

This is where standards enter the story.

Part 3: Standards

standard /?stand?d/ noun

something used as a measure, norm, or model in [comparative] evaluations.

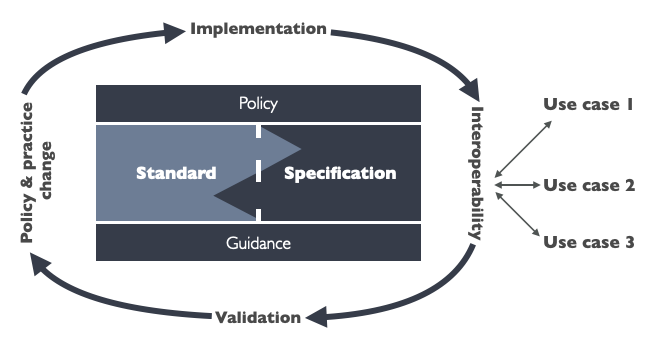

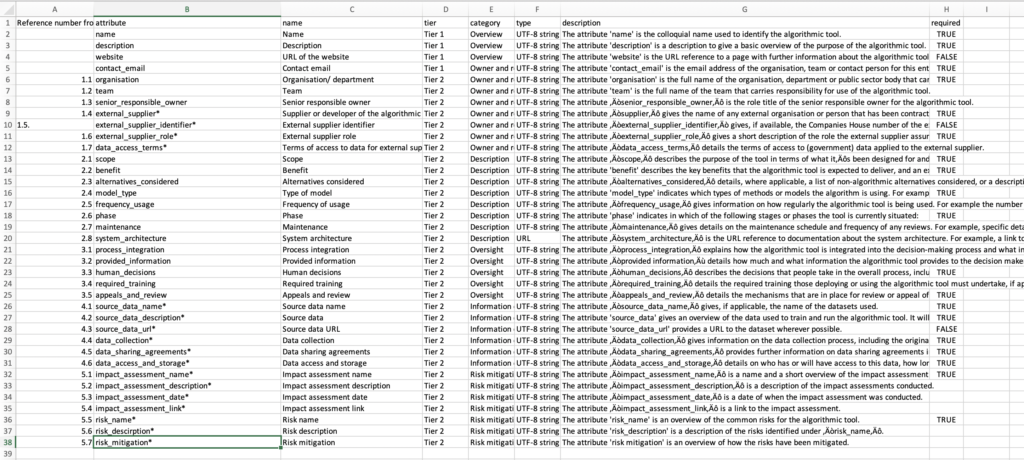

The first thing I want to note about ‘standards’ is that the term is used in very different ways by different communities of practice. For a technical community, the idea of a data standard more-or-less relates to a technical specification or even schema, by which the exact way that certain information should be represented as data is set out in minute detail. To assess if data ‘meets’ the standard is a question of how the data is presented. For a policy audience, talk of data standards may be interpreted much more as a question of collection and disclosure norms. To assess if data meets the standard here is more a question of what data is presented. In practice, these aspects interrelate. With anything more than a few records, to assess ‘what’ has been disclosed requires processing data, and that requires it to be modeled according to some reasonable specification.

The second thing I want to note about standards is that they are highly interconnected. If we agree upon a standard for the disclosure of government budget information, for example, then in order to produce data to meet that standard, government may need to check that a whole range of internal systems are generating data in accordance with the standard. The standard for disclosure that sits on the boundary of a public data infrastructure can have a significant influence on other parts of that infrastructure, or its operation can be frustrated when other parts of the infrastructure can’t produce the data it demands.

The third thing to note is that a standard is only really a standard when it has multiple users. In fact, the greater the community of users, the stronger, in effect, the standard is.

So – with these points in mind, let’s look at how a turn to transparency and open data has created both pressure for application of data standards, and an opening for participatory shaping of data infrastructures.

One of the early rallying cries of the open data movement was ‘Raw Data Now’. Yet, it turns out raw data, as a set of database dumps of selected tables from the silo datasets of the state does not always produce effective transparency. What it does do, however, is create the start of a conversation between citizen, private sector and state over the nature of the data collected, held and shared.

Take for example this export from a council’s financial system in response to a central government policy calling for transparency on spend over £500.

| Service Area |

BVA Cop |

ServDiv Code |

Type |

Code |

Date |

Transaction No. |

Amount |

Revenue / Capital |

Supplier |

| Balance Sheet |

|

900551 |

Insurance Claims Payment (Ext) |

47731 |

31.12.2010 |

1900629404 |

50,000.00 |

Revenue |

Zurich Insurance Co |

| Balance Sheet |

|

900551 |

Insurance Claims Payment (Ext) |

47731 |

01.12.2010 |

1900629402 |

50,000.00 |

Revenue |

Zurich Insurance Co |

| Balance Sheet |

|

933032 |

Other income |

82700 |

01.12.2010 |

1900632614 |

-3,072.58 |

Revenue |

Unison Collection Account |

| Balance Sheet |

|

934002 |

Transfer Values paid to other schemes |

11650 |

02.12.2010 |

1900633491 |

4,053.21 |

Revenue |

NHS Pensions Scheme Account |

| Balance Sheet |

|

900601 |

Insurance Claims Payment (Ext) |

47731 |

06.12.2010 |

1900634912 |

1,130.54 |

Revenue |

Shires (Gloucester) Ltd |

| Balance Sheet |

|

900652 |

Insurance Claims Payment (Int) |

47732 |

06.12.2010 |

1900634911 |

1,709.09 |

Revenue |

Bluecoat C Of E Primary School |

| Balance Sheet |

|

900652 |

Insurance Claims Payment (Int) |

47732 |

10.12.2010 |

1900637635 |

1,122.00 |

Revenue |

Christ College Cheltenham |

It comes from data generated for one purpose (the council’s internal financial management), now being made available for another purpose (external accountability), but that might also be useful for a range of further purposes (companies looking to understand business opportunities; other council’s looking to benchmark their spending, and so-on). Stripped of its context as part of internal financial systems, the column headings make less sense: what is BVA COP? Is the date the date of invoice? Or of payment? What does each ServDiv Code relate to? The first role of any standardization is often to document what the data means: and in doing so, to surface unstated assumptions.

But standardization also plays a role in allowing the emerging use cases for a dataset to be realized. For example, when data columns are aligned comparison across council spending is facilitated. Private firms interested in providing such comparison services may also have a strong interest in seeing each of the authorities providing data doing so to a common standard, to lower their costs of integrating data from each new source.

If standards are just developed as the means of exchanging data between government and private sector re-users of the data, the opportunities for constructing a participatory data infrastructure are slim. But when standards are explored as part of the transparency agenda, and as part of defining both the what and the how of public disclosure, such opportunities are much richer.

When budget and spend open data became available in Sao Paulo in Brazil, a research group at University of Sao Paulo, led by Gisele Craviero, explored how to make this data more accessible to citizens at a local level. They found that by geocoding expenditure, and color coding based on planned, committed and settled funds, they could turn the data from impenetrable tables into information that citizens could engage with. More importantly, they argue that in engaging with government around the value of geocoded data “moving towards open data can lead to changes in these underlying and hidden process [of government data creation], leading to shifts in the way government handles its own data” [22]

The important act here was to recognize open data-enabled transparency not just as a one-way communication from government to citizens, but as an invitation for dialog about the operation of the public data infrastructure, and an opportunity to get involved – explaining that, if government took more care to geocode transactions in its own systems, it would not have to wait for citizens to participate in data use and to expend the substantial labour on manually geocoding some small amount of spending, but instead the opportunity for better geographic analysis of spending would become available much more readily inside and outside the state.

I want to give three brief examples of where the development, or not, of standards is playing a role in creating more participatory data infrastructures, and in the process to draw out a couple of other important aspects of thinking about transparency and standardization as part of the strategic toolkit for asserting citizen rights in the context of smart cities.

Part 4: Examples

Contracts

My first example looks at contracts for two reasons. Firstly, it’s an area I’ve been working on in depth over the last few years, as part of the team creating and maintaining the Open Contracting Data Standard. But, more importantly, its an under-explored aspect of the smart city itself. For most cities, how transparent is the web of contracts that establishes the interaction between public and private players? Can you easily find the tenders and awards for each component of the new city infrastructure? Can you see the terms of the contracts and easily read-up on who owns and controls each aspect of emerging public data infrastructure? All too often the answer to these questions is no. Yet, when it comes to procurement, the idea of transparency in contracting is generally well established, and global guidance on Public Private Partnerships highlights transparency of both process and contract documents as an essential component of good governance.

The Open Contracting Data Standard emerged in 2014 as a technical specification to give form to a set of principles on contracting disclosure. It was developed through a year-long process of research, going back and forth between a focus on ‘data supply’ and understanding the data that government systems are able to produce on their contracting, and ‘data demand’, identifying a wide range of user groups for this data, and seeking to align the content and structure of the standard with their needs. This resulted in a standard that provides a framework for publication of detailed information at each stage of a contracting process, from planning, through tender, award and signed contract, right through to final spending and delivery.

Meeting this standard in full is quite demanding for authorities. Many lack existing data infrastructures that provide common identifiers across the whole contracting process, and so adopting OCDS for data disclosure may involve some elements of update to internal systems and processes. The transparency standard has an inwards effect, shaping not only the data published, but the data managed. In supporting implementation of OCDS, we’ve also found that the process of working through the structured publication of data often reveals as yet unrecognized data quality issues in internal systems, and issues of compliance with existing procurement policies.

Now, two of the critiques that might be offered of standards is that, as highly technical objects their development is only open to participation from a limited set of people, and that in setting out a uniform approach to data publication, they are a further tool of centralization. Both these are serious issues.

In the Open Contracting Data Standard we’ve sought to navigate them by working hard on having an open governance process for the standard itself, and using a range of strategies to engagement people in shaping the standard, including workshops, webinars, peer-review processes and presenting the standard in a range of more accessible formats. We’re also developing an implementation and extensions model that encourages local debate over exactly which elements of the overall framework should be prioritized for publication, whilst highlighting the fields of data that are needed in order to realize particular use-cases.

This highlights an important point: standards like OCDS are more than the technical spec. There is a whole process of support, community building, data quality assurance and feedback going on to encourage data interoperability, and to support localization of the standard to meet particular needs.

When standards create the space, then other aspects of a participatory data infrastructure are also enabled and facilitated. A reliable flow of data on pipeline contracts may allow citizens to scrutinize the potential terms of tenders for smart city infrastructure before contracts are awarded and signed, and an infrastructure with the right feedback mechanisms could ensure, for example, that performance-based payments to providers are properly influenced by independent citizen input.

The thesis here is one of breadth and depth. A participatory developed open standard allows a relatively small-investment intervention to shape a broad section of public data infrastructure, influencing the internal practice of government and establishing the conditions for more ad-hoc deep-dive interventions, that allow citizens to use that data to pursue particular projects of change.

Earth

The second example explores this in the context of land. Who owns the smart city?

The Open Data Index and Open Data Barometer studies of global open data availability have had a ‘Land Ownership’ category for a number of years, and there is a general principle that land ownership information should, to some extent, be public. However, exactly what should be published is a tricky question. An over-simplified schema might ignore the complex realities of land rights, trying to reduce a set of overlapping claims to a plot number and owner. By contrast, the narrative accounts of ownership that often exist in the documentary record may be to complex to render as data [24]. In working on a refined Open Data Index category, the Cadasta Foundation 23 noted that opening up property owners names in the context of a stable country with functioning rule of law “has very different risks and implications than in a country with less formal documentation, or where dispossession, kidnapping, and or death are real and pervasive issues” 23.

The point here is that a participatory process around the standards for transparency may not, from the citizen perspective, always drive at more disclosure, but that at times, standards may also need to protect the ‘strategic invisibility’ of marginalized groups [25]. In the United Kingdom, although individual titles can be bought for £3 from the Land Registry, no public dataset of title-holders is available. However, there are moves in place to establish a public dataset of land owned by private firms, or foreign owners, coming in part out of an anti-corruption agenda. This fits with the idea that, as Sunil Abraham puts it, “privacy should be inversely proportional to power” 26.

Central property registers are not the only source of data relevant to the smart city. Public authorities often have their own data on public assets. A public conversation on the standards needed to describe this land, and share information about it, is arguable overdue. Again looking at the UK experience, the government recently consulted on requiring authorities to record all information on their land assets through the Property Information Management system (ePIMS): centralizing information on public property assets, but doing so against a reductive schema that serves central government interests. In the consultation on this I argued that, by contrast, we need an approach based on a common standard for describing public land, but that allows local areas the freedom to augment a core schema with other information relevant to local policy debates.

Air

From the earth, let us turn very briefly to the air. Air pollution is a massive issue, causing millions on premature deaths worldwide every year. It is an issue that is particularly acute in urban areas. Yet, as the Open Data Institute note “we are still struggling to ‘see’ air pollution in our everyday lives” 27. They report the case of decision making on a new runway at Heathrow Airport, where policy makers were presented with data from just 14 NO2 sensors. By contrast, a network of citizen sensors provided much more granular information, and information from citizen’s gardens and households, offering a different account from those official sensors by roads or in fields.

Mapping the data from official government air quality sensors reveals just how limited their coverage is: and backs up the ODI’s calls for a collaborative, or participatory, data infrastructure. In a 2016 blog post, Jamie Fawcett describes how:

“Our current data infrastructure for air quality is fragmented. Projects each have their own goals and ambitions. Their sensor networks and data feeds often sit in silos, separated by technical choices, organizational ambition and disputes over data quality and sensor placement. The concerns might be valid, but they stand in the way of their common purpose, their common goals.”

He concludes “We need to commit to providing real-time open data using open standards.”

This is a call for transparency by both public and private actors: agreeing to allow re-use of their data, and rendering it comparable through common standards. The design of such standards will need to carefully balance public and private interests, and to work out how the costs of making data comparable will fall between data publishers and users.

Part 5: Recap

So, to briefly recap:

- I want to draw attention to the data infrastructures of the smart city and the modern state;

- I’ve suggested that open data and transparency can be powerful tools in performing the kind of infrastructural inversion that brings the context and history of datasets into view and opens them up to scrutiny;

- I’ve furthermore argued that transparency policy opens up an opportunity for a two-way dialogue about public data infrastructures, and for citizen participation not only in the use and production of data, but also in setting standards for data disclosure;

- I’ve then highlighted how standards for disclosure don’t just shape the data that enters the public domain, but they also have an upwards impact on the shape of the public data infrastructure itself.

Taken together, this is a call for more focus on the structure and standardization of data, and more work on exploring the current potential of standardization as a site of participation, and an enabler of citizen participation in future.

If you are looking for a more practical set of takeaways that flow from all this, let me offer a set of questions that can be asked of any smart cities project, or indeed, any data-rich process of governance:

- (1) What information is pro-actively published, or can be demanded, as a result of transparency and right to information policies?

- (2) What does the structure of the data reveal about the process/project it relates to?

- (3) What standards might be used to publish this data?

- (4) Do these standards provide the data I, or other citizens, need to be empowered in relevant to this process/project?

- (5) Are these open standards? Whose needs were they designed to serve?

- (6) Can I influence these standards? Can I afford not to?

References

1: https://www.google.co.uk/search?q=define%3Ainfrastructure, accessed 17th August 2017

2: Star, S., & Ruhleder, K. (1996). Steps Toward an Ecology of Infrastructure: Design and Access for Large Information Spaces. Information Systems Research, 7(1), 111–134.

3: Bowker, G. C., & Star, S. L. (2000). Sorting Things Out: Classification and Its Consequences. The MIT Press.

4: Goldsmith, S., & Crawford, S. (2014). The responsive city. Jossey-Bass.

5: Kitchin, R. (2014). The Data Revolution: Big Data, Open Data, Data Infrastructures and Their Consequences. SAGE Publications.

6: The Danish Government. (2012). Good Basic Data for Everyone – a Driver for Growth and Efficiency, (October 2012)

7: Bartha, G., & Kocsis, S. (2011). Standardization of Geographic Data: The European INSPIRE Directive. European Journal of Geography, 22, 79–89.

10: Guldi, J. (2012). Roads to power: Britain invents the infrastructure state.

[11]: Gray, J., & Davies, T. (2015). Fighting Phantom Firms in the UK : From Opening Up Datasets to Reshaping Data Infrastructures?

[12]: Gray, J., & Tommaso Venturini. (2015). Rethinking the Politics of Public Information: From Opening Up Datasets to Recomposing Data Infrastructures?

[13]: Gray, J. (2015). DEMOCRATISING THE DATA REVOLUTION: A Discussion Paper

[14]: Arnstein, S. R. (1969). A ladder of citizen participation. Journalof the American Institute of Planners, 34(5), 216–224.

[16]: Ribes, D., & Baker, K. (2007). Modes of social science engagement in community infrastructure design. Proceedings of the 3rd Communities and Technologies Conference, C and T 2007, 107–130.

[17]: Davies, T. (2010, September 29). Open data, democracy and public sector reform: A look at open government data use from data.gov.uk.

[18]: Davies, T. (2014). Open Data Policies and Practice: An International Comparison.

[19]: Fung, A., Graham, M., & Weil, D. (2007). Full Disclosure: The Perils and Promise of Transparency (1st ed.). Cambridge University Press.

[22]: Craveiro, G. S., Machado, J. A. S., Martano, A. M. R., & Souza, T. J. (2014). Exploring the Impact of Web Publishing Budgetary Information at the Sub-National Level in Brazil.

[24]: Hetherington, K. (2011). Guerrilla auditors: the politics of transparency in neoliberal Paraguay. London: Duke University Press.

[25]: Scott, J. C. (1987). Weapons of the Weak: Everyday Forms of Peasant Resistance.