[Summary: looking at the limits of large language models, and finding the place they might play.]

Joseph Foti, Principal Advisor on Emerging Issues for the Open Government Partnership, has been exploring the role of artificial intelligence as a tool for government accountability in low data environments. His conclusions, that “AI won’t replace accountability actors, especially in low-data contexts, but done right, it can help them see further, move faster, and be more accurate” made me think of a recent conversation with Tiago Piexoto, on the possibility that AI might overcome the ‘infomediary gap’ that arguably acted as a significant brake on the potential of open data.

In short, if the potential for transparency through open data to drive accountability at scale was stymied by the difficulty of finding and sustaining intermediaries who could translate raw data into actionable information, then can recent developments in AI, and the arrival of generative AI in particular, fill that gap?

Joe takes as a starting point that journalists, policy makers and activists are likely to use generative AI as an information source in any case, and therefore this creates both a renewed case for investing in the production of good quality data, and a need to find ‘workarounds’ for using AI for accountability research work in low resource contexts.

I want to offer a slightly sceptical build on Joe’s post, and in turn, a reflection on if and how recent AI development might revitalise open data.

1) We should name and accept the fundamental limits of generative AI until or unless they are overcome

The narrative that AI is an inevitable component of all workflows, or that AI tools are capable of just about any task, should not be taken for granted. Ever since breaking into popular awareness through ChatGPT, large language models (LLMs) have not overcome the powerful 2021 ‘stochastic parrots’ critique that while they generate plausible language they don’t have any ‘understanding’ of concepts or truth. In short, bare generative AI tools are capable of error-prone (but often quite useful) synthesis of information and knowledge by virtue to patterns in their training texts, but are not capable of generating knowledge.

This is a really important distinction for thinking about accountability work, and reflected in some of Joe’s workarounds. Whilst in a high-resource environment, an LLM may be able to synthesise existing documented knowledge on corruption or accountability issues (or indeed, knowledge that can provide useful background for a researcher investigating a potential issue) – where the issues have not hitherto been documented in prose, a general purpose LLM isn’t going to serve up new knowledge.

We also need to consider the limitations of different approaches to get more local context into LLMs. We can identify broadly three routes by which data from low-resource topics might end up in generative AI responses:

- Model training. GPT-4 is estimated to have trained on roughly 1 petabyte of data, and cost tens of millions of dollars in compute power. Retraining models only takes place periodically: and so there can be a significant lag between data making it into ‘crawls’ and datasets fed into models, and then into a released model.

- Fine tuning. Relatively small datasets, and much lower compute costs, are involved in fine-tuning an LLM: though generally this requires some amount of ‘labelled data’ (i.e. data already human classified – rather than just a corpus of documents) so may have greater human labour costs involved.

- Retrieval Augmented Generation (RAG) . This is a common feature of how we experience many LLMs today, when they either draw on user-supplied documents, or search the web for extra content, to fit into the context-window used to respond to user prompts. RAG essentially combines generative AI supported search (of your own, or an open repository of information) with the text synthesis capability of AI.

For each of these approaches we should consider (a) the labour involved in improving LLM outputs; and (b) the alternative uses of that labour and/or the outputs of that labour.

For example if, to help address extractives corruption, we plan to bring together a collection of license documents into a database for RAG, do we also consider other non-AI ways we could use the resulting corpus? Or rather than putting resource into click-work labelling of data to fine-tune an LLM, might we be better creating tools and processes that help active citizens to engage with the meaning of, and potential response to, the documents we’ve collected?

When we approach specific forms of AI as distinctly limited technologies within any given workflow, rather than magical general purpose agents, we can better evaluate where they expand our capabilities, and where they risk misleading and eroding our effectiveness.

2) LLMs are not great at structured data

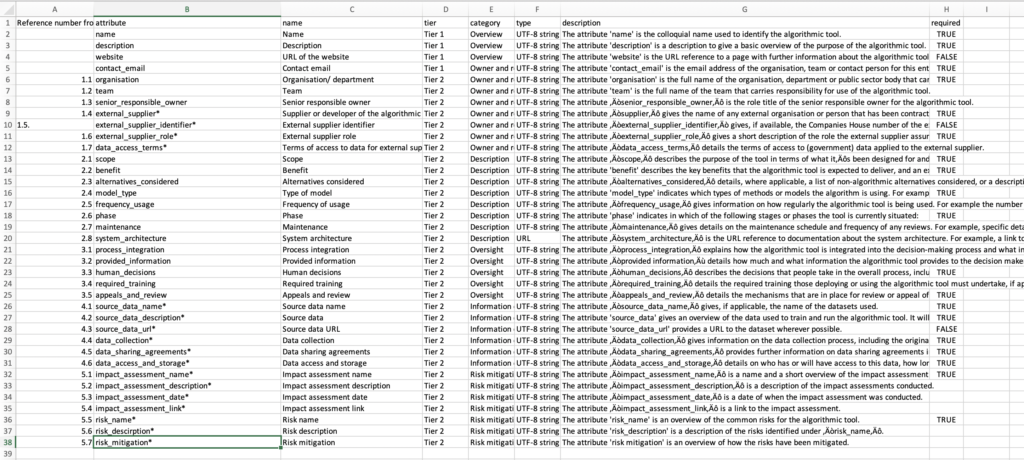

As this paper highlights, in general, LLMs are not tailored to working with structured data. As a simplification: it appears that an LLM sees tabular data as a set of relationships between neighbouring words and terms, and not as a set of columns, rows and abstracted data points. This has some interesting consequences both for how open data might be fed into LLM training and the right models for using AI as a tool of accountability where our source material is structured.

Perhaps the more interesting application of generative AI is not as an interface to structured data, but as a tool for extracting structured data from documents. For example, a fine-tuned vision model might be capable of extracting structured data from printed financial records or beneficial ownership disclosures for later analysis, whilst a general purpose LLM might be poorly suited to RAG-based search of the same documents.

3) Using AI for ‘signal’ detection involves an algorithmic approach whether with Narrow or General Purpose AI

One of the main infomediary roles in transparency and accountability is finding signal in the noise of large datasets or flows of information. We’ve long been able to develop, and, in cases with enough labelled data, train, algorithms that can flag data points worthy further investigation – but this has often proven very labour intensive, and led to a limited supply of sustainable tools. In this context, generative AI tools which appear at first glance to allow signal to be found by simply prompting can look appealing. But, in practice, if we want to get away from false positives and negatives, it takes a more systematic and technical approach.

For example, this recent paper on Automation of Systematic Reviews with Large Language Models describes an AI agent-based workflow, chaining together different LLM-enabled processing steps to identify, assess and evaluate evidence. Whilst this shows some of the promise of AI tools, it also demonstrates the level of careful workflow design required to use AI in truth-seeking contexts: and in many cases we should keep in mind that running step-by-step data processing instructions on top of probabilistic LLMs may be a more computational (and environmentally) costly, and still more error prone, approach than running more directly in code.

4) LLMs might lower the technical barriers to structured data analysis

One of the big barriers to the emergence of infomediaries has been the technical and domain knowledge skill required to make good use of data. It is perhaps here that LLMs are quite well-suited as a tool: trained on a wealth of resources that discuss how to analyse data, and able to suggest ‘good enough’ code or formula to get started with a dataset – albeit with the risk that they leave users with many important ‘unknown unknowns’ that might affect the quality of analysis produced.

But – it’s a different approach to focus on the LLM as a tool to help provide contextual teaching on the analysis of documents and data, rather than to take on that analysis – and perhaps a more appropriate use.

5) We should support local data inputs: but not restrict our vision to generative AI use

In his post, Joe reflects on the need to ‘build a data corpus based on a limited set of local priorities’, and the need for local data partnerships to develop and sustain this kind of resource.

At the hyperlocal level in Gloucestershire, sparked by the NewCommons.ai challenge, we’ve also been thinking about how to bring together collections of data that could support AI tools to generate richer local community profiles and provide actionable information for community groups through generative AI interfaces. But we’ve also been thinking about the other ways that data might be used: making sure we don’t only shape our data practices around centralising AI systems – and focussing on data collection and sharing as a social process.

If the data-demands of AI are to become a driver for new community and open data efforts, we have important questions to answer about whether we’re handing over data and power to centralised systems, or whether we are developing, maintaining and governing data in ways that empower communities.

Working with, working around and working in other ways

The notes above are preliminary and incomplete. If I can try and draw out some initial conclusions, they might be that:

- Alongside recognising the momentum of AI practice and seeking to shift this towards responsible practice, we should keep developing alternative narratives of our informational future;

- We need to get really specific about which parts of accountability workflows current generative AI tools are suited to, and be clear where they don’t fit;

- AI isn’t a drop-in fix for the infomediary gap in open data theories of change, but it might have a role in structuring data, and supporting analysts to generate insight.

In closing, let me quote from the 2025 Human Development Report:

“…we should not task machines with decisions simply because they now seem capable of making them; we should instead do so based on whether ceding those decisions expands or contracts our agency and freedoms.” Human Development Report 2025