[Summary: an introduction to data standards, their role in development projects, and critical perspectives for thinking about effective standardisation and its social impacts]

I was recently invited to give a presentation as part of a GIZ ICT for Agriculture talk series, focussing on the topic of data standards. It was a useful prompt to try and pull together various threads I’ve been working on around concepts of standardisation, infrastructure, ecosystem and institution – particularly building on recent collaboration with the Open Data Institute. As I wrote out the talk fairly verbatim, I’ve reproduced it in blog form here, with images from the slides. The slides with speaker notes are also available shared here. Thanks to Lars Kahnert for the invite and opportunity to share these thoughts.

Introduction

In this talk I will explore some of the ways in which development programmes can think about shaping the role of data and digital platforms as tools of economic, social and political change. In particular, I want to draw attention to the often dry-sounding world of data standards, and to highlight the importance of engaging with open standardisation in order to avoid investing in new data silos, to tackle the increasing capture and enclosure of data of public value, and to make sure social and developmental needs are represented in modern data infrastructures.

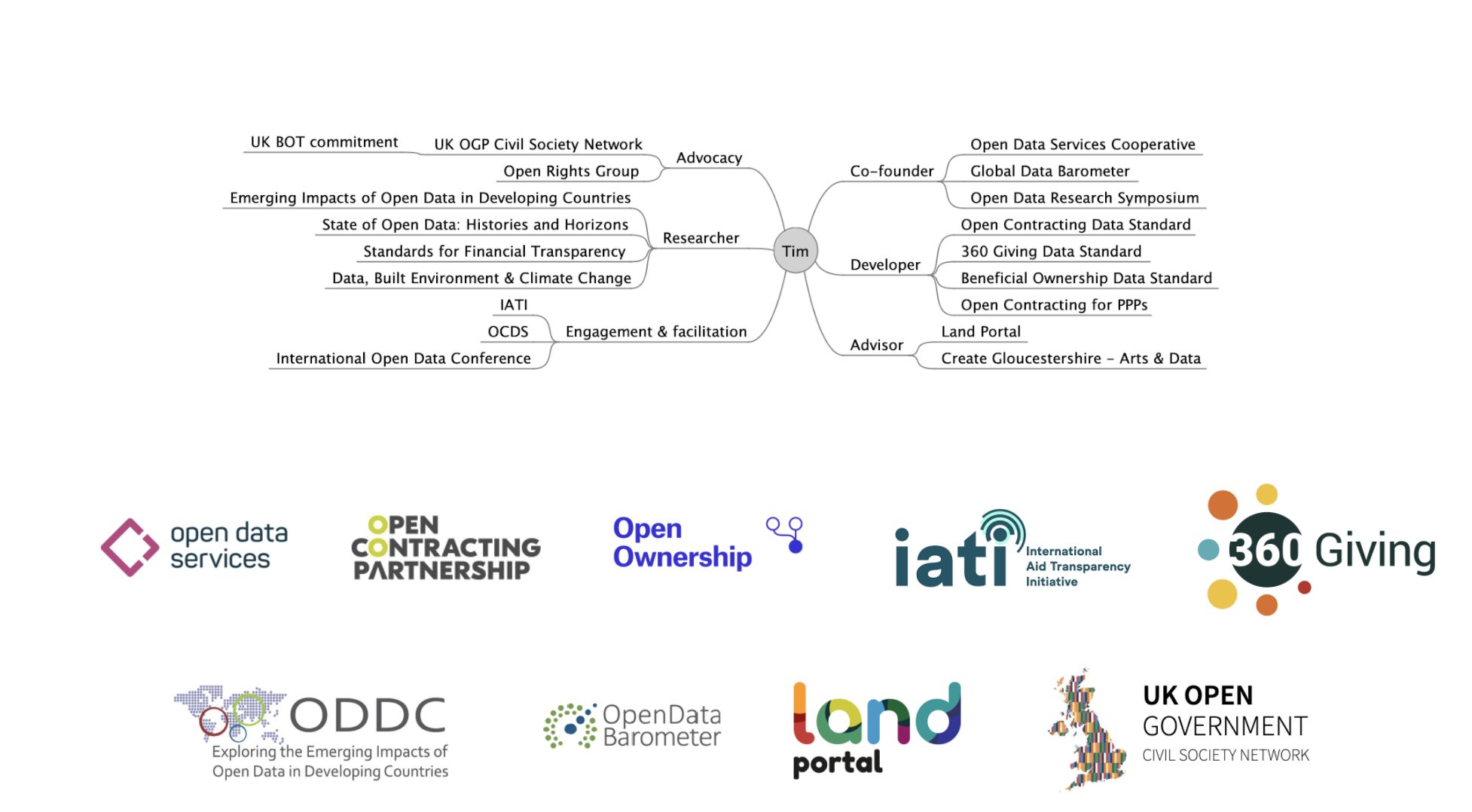

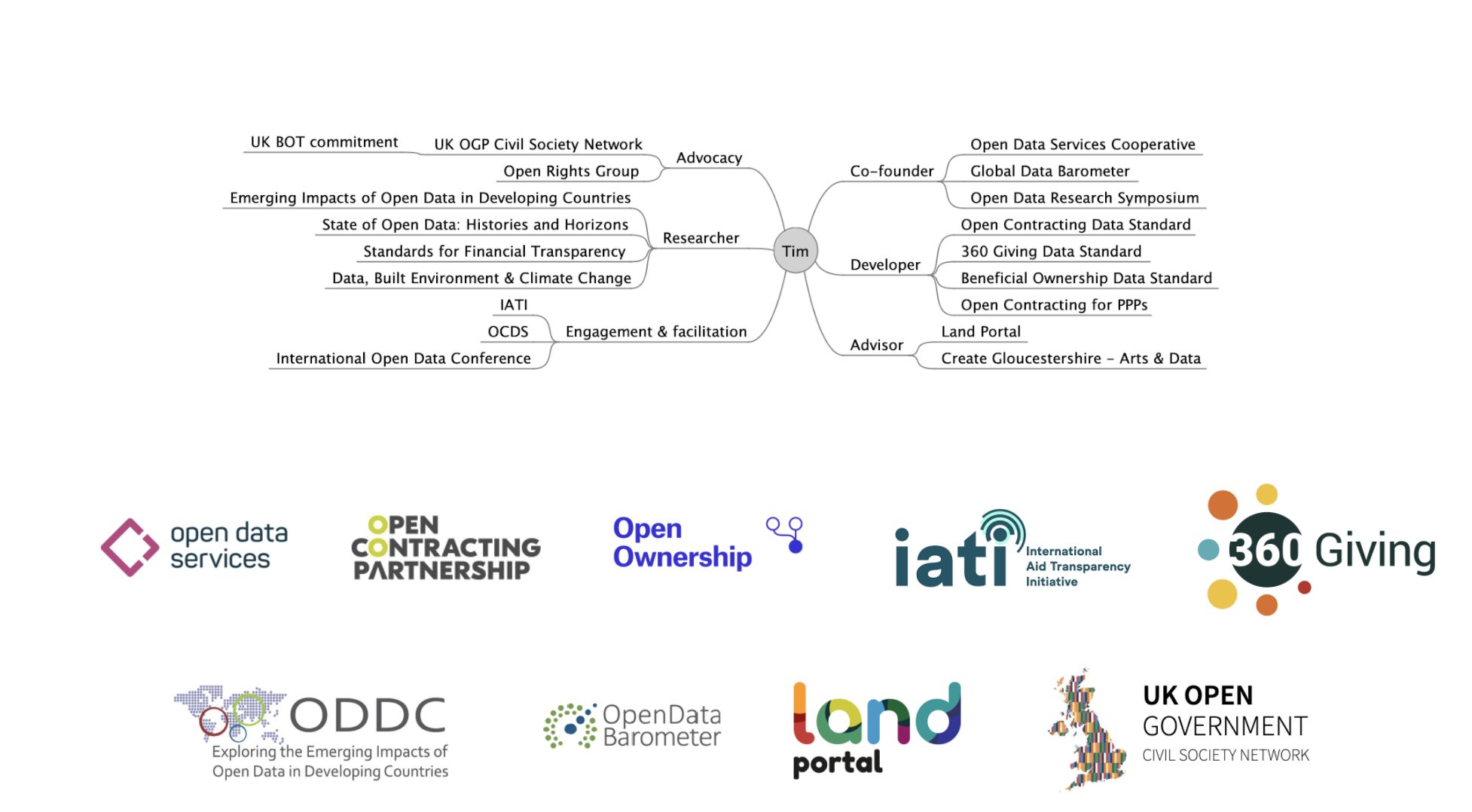

By way of introduction to myself: I’ve worked in various parts of data standard development and adoption – from looking at the political and organisational policies and commitments that generate demand for standards in the first place, through designing technical schema and digging into the minutiae of how particular data fields should be defined and represented, to supporting standard adoption and use – including supporting the creation of developer and user ecosystems around standardised data.

I also approach this from a background in civic participation, and with a significant debt to work in Information Infrastructure Studies, and currently unfolding work on Data Feminism, Indigenous Data Sovereignty, and other critical responses to the role of data in society.

This talk also draws particularly on some work in progress developed through a residency at the Rockefeller Bellagio Centre looking at the intersection of standards and Artificial Intelligence: a point I won’t labour – as I fear a focus on ‘AI’ – in inverted commas – can distract us from looking at many more ‘mundane’ (also in inverted commas) uses of data: but I will say at this point that when we think about the datasets and data infrastructures our work might create, we need to keep in mind that these will likely end up being used to feed machine learning models in the future, and so what gets encoded, and what gets excluded from shared datasets is a powerful driver of bias before we even get to the scope of the training sets, or the design of the AI algorithms themselves.

Standards work is AI work.

Enough preamble. To give a brief outline: I’m going to start with a brief introduction to what I’m talking about when I say ‘data standards’, before turning to look at the twin ideas of data ecosystems and data infrastructures. We’ll then touch on the important role of data institutions, before asking why we often struggle to build open infrastructures for data.

An introduction to standards

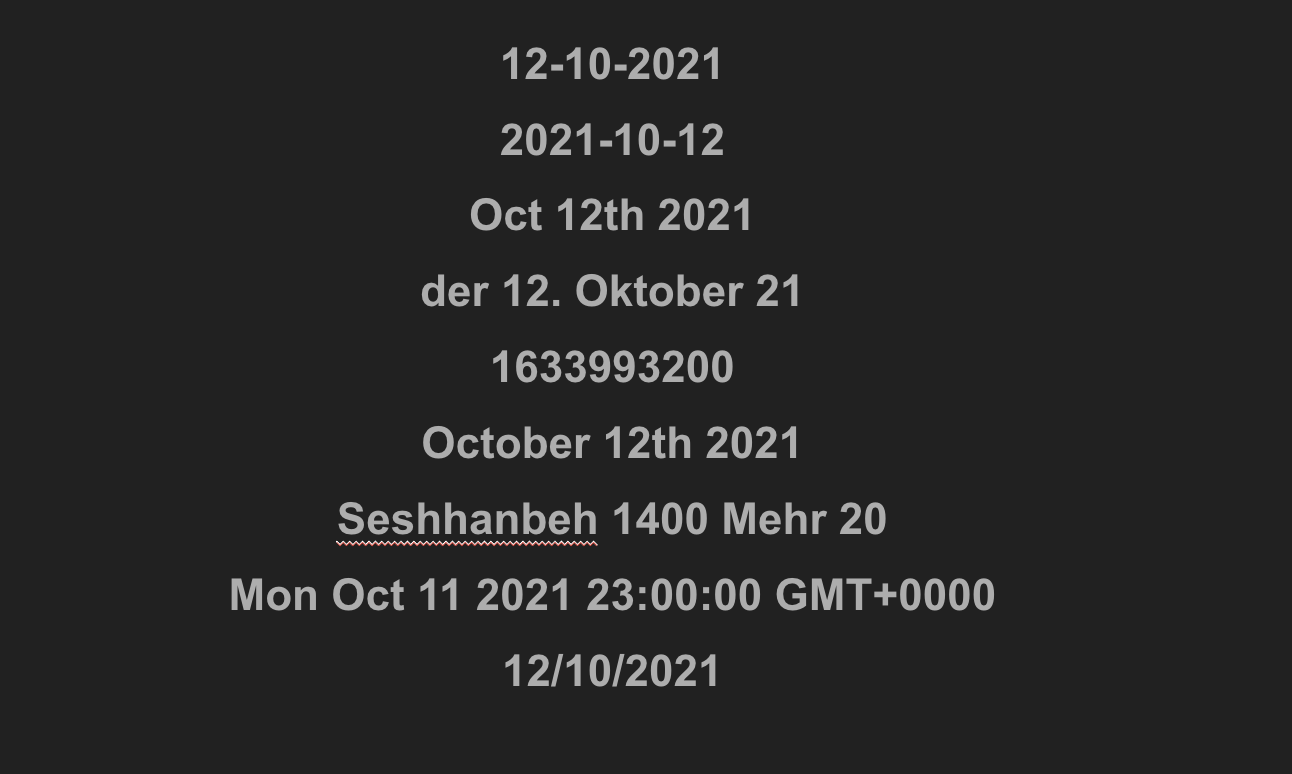

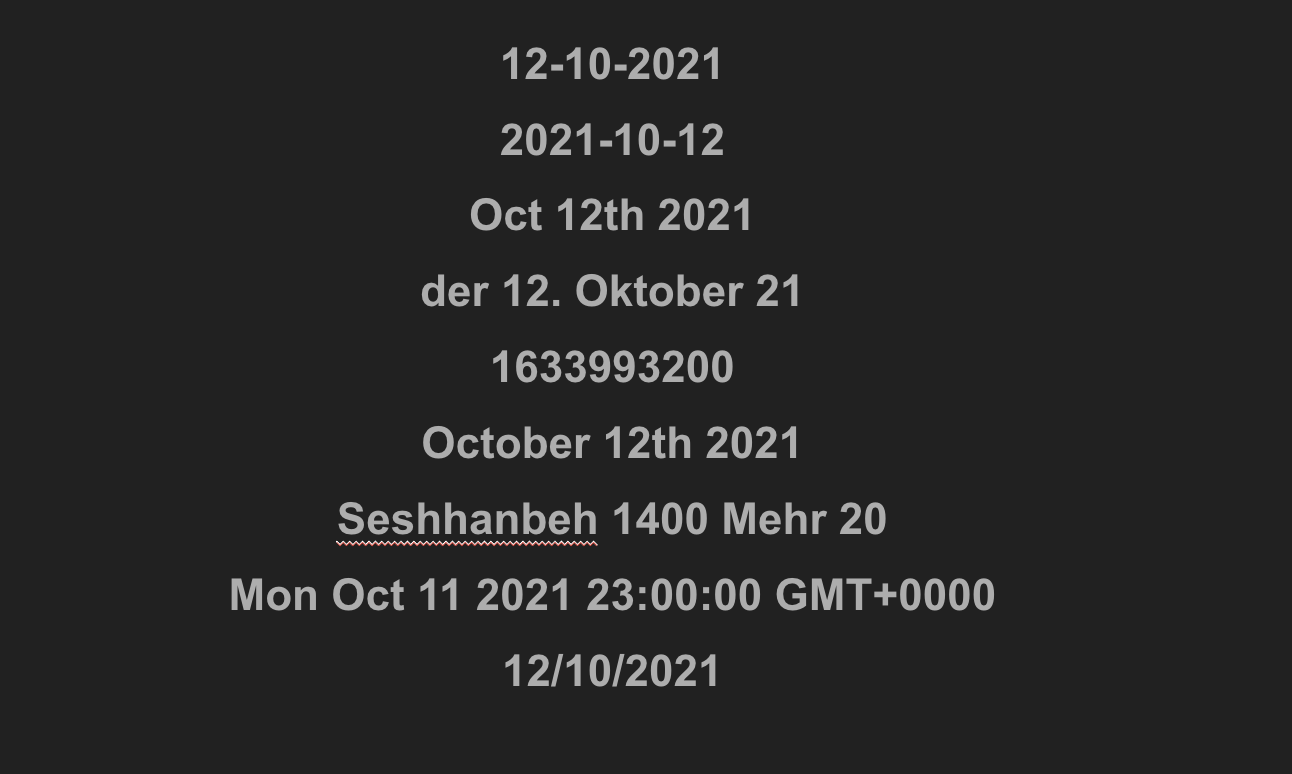

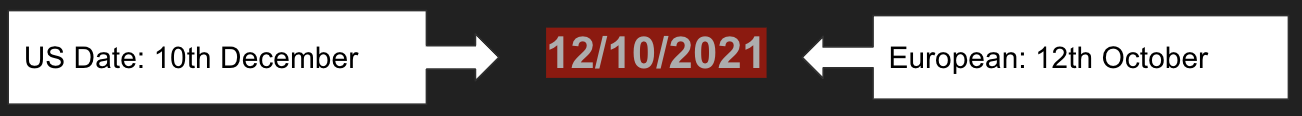

Each line in the image above is a date. In fact – they are all the same date. Or, at least, they could be.

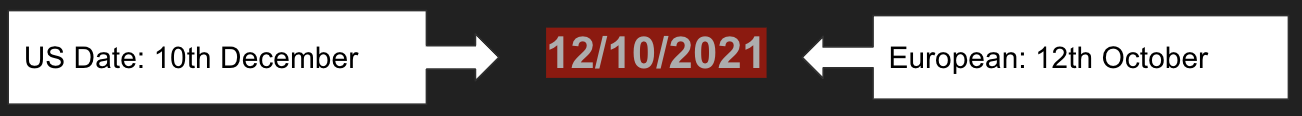

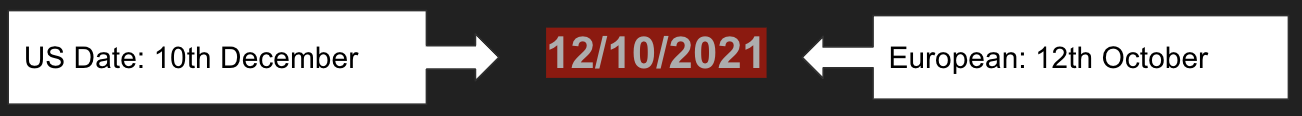

Whilst you might be able to conclusively work out most of them are the same date, and we could even write computer rules to convert them, because the way we write dates in the world is so varied, some remain ambiguous.

Fortunately, this is (more or less) a solved problem. We have the ISO8601 standard for representing dates. Generally, developers present ‘ISO Dates’ in a string like this:

This has some useful properties. You can use simple sorting to get things in date order, you can include the time or leave it out, you can provide timezone offsets for different countries, and so-on.

If everyone exchanging date converts their dates into this standard form, the risk of confusion is reduced, and a lot less time has to be spent cleaning up the data for analysis.

It’s also a good example of a building block of standardisation for a few other reasons:

- The ISO in the name stands for ‘International Organization for Standardization’: the vast international governance and maintenance effort behind this apparently simple standard, which was first released in 1988, and last revised just two years ago.

- The ‘8601’ is the standard number. There are a lot of standards (though not all ISO standards are data standards)

- Uses of this one standard relies on lots of other standards: such as the way the individual numbers and characters are encoded when sent over the Internet or other media, and even standards for the reliable measurement of time itself.

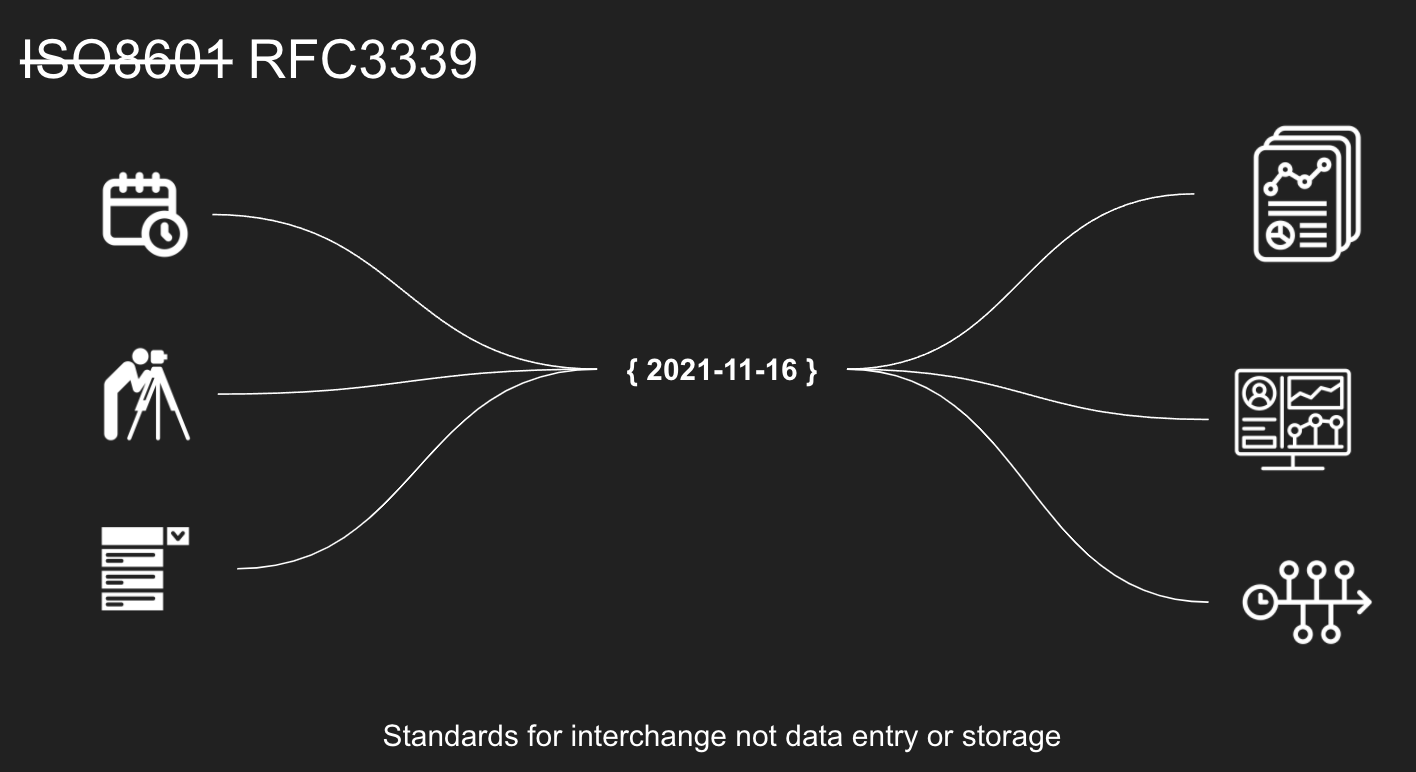

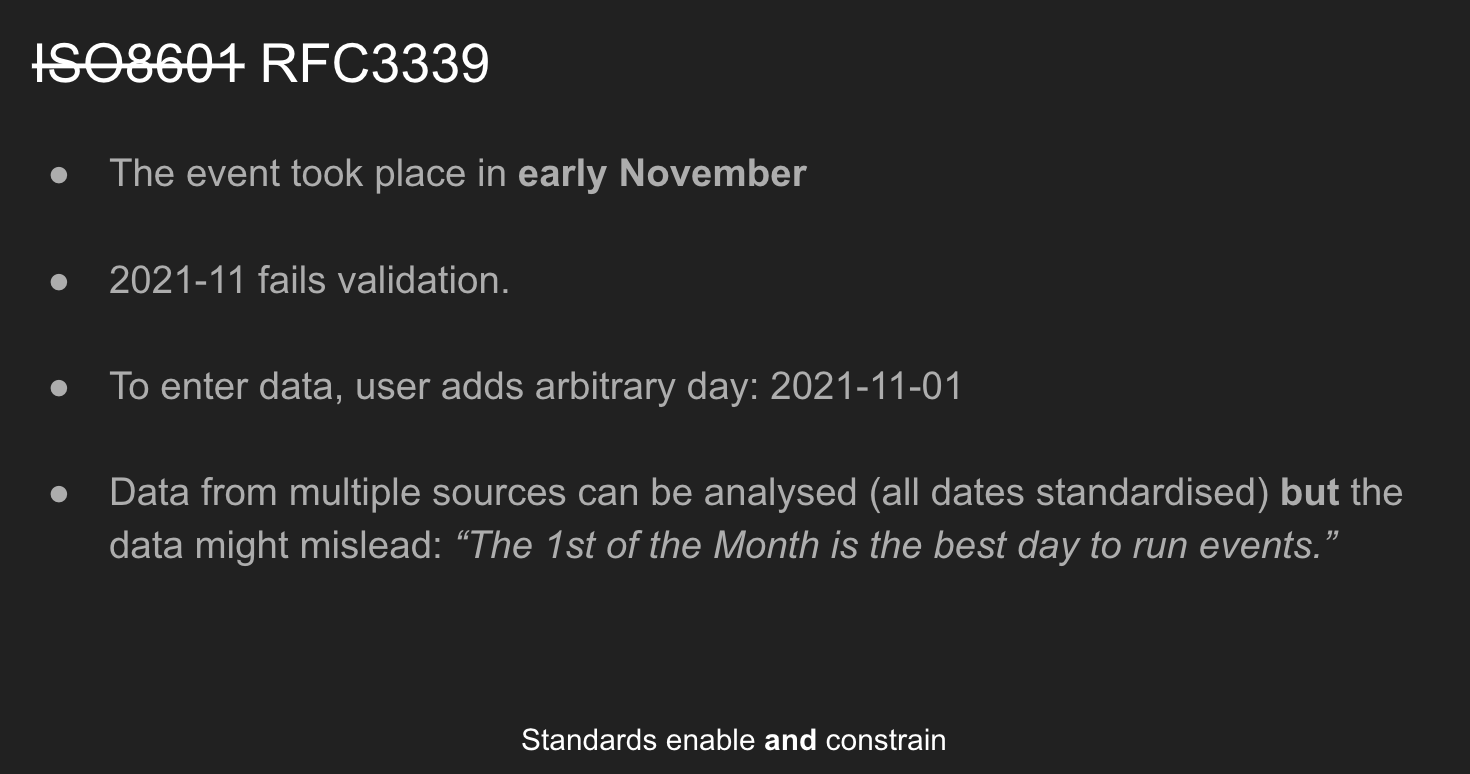

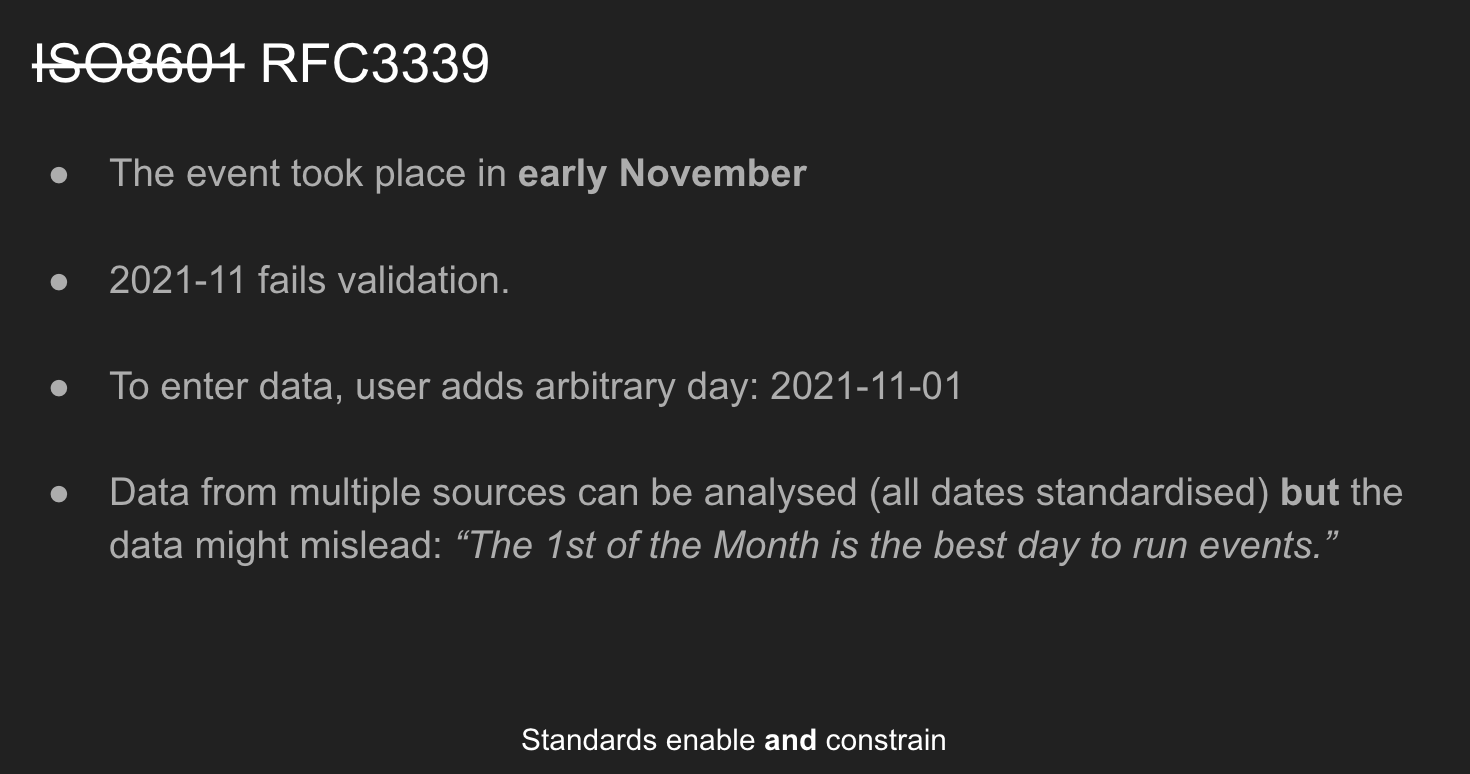

- And, like many standards, ISO 8601 is, in practice, rarely fully implemented. For example, whilst developers talk of using the ISO standard, what they actually rely on is from RFC3339, which leaves out lots of things in the ISO standard such as imprecise dates. As a rule of thumb: people copy implementations rather than read specifications.

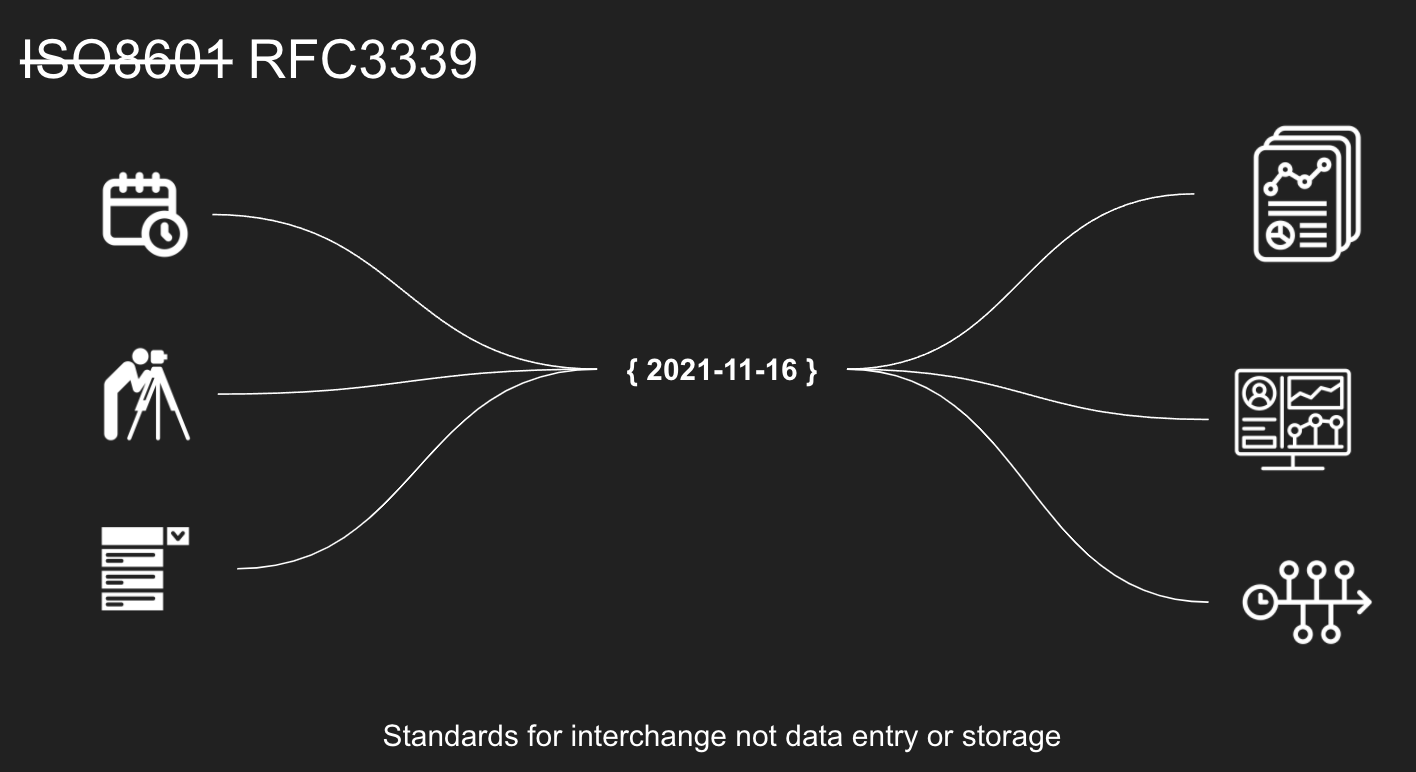

ISO8601 is called an Interchange standard– that is, most systems don’t internally store data in ISO8601 when they want to process it, and it’s a cumbersome form that makes everyone write out the date in ISO format, instead – the standard sits in the middle – limiting the need to understand the specific quirks of each origin of data, and allowing receivers to streamline the import of data into their own models and methods.

And to introduce the first critical issue of standardisation – as actually implemented – it constrains what can be expressed: sometimes for good, and sometimes problematically.

For example, RFC3339 omits imprecise dates. That is, if you know that something happened in October 2021, but not which date – your data will fail validation if you leave out the day. So to exchange data using the standard you are forced to make up a day – often 1st of the month. A paper form would have no such constraint: users would just leave the ‘day’ box blank. The impact may be nothing, or, if you are trying to exchange data from certain places where, for legacy reasons, the day of the month of an event is not easily known – that data could end up distorting later analysis.

So – even these small building blocks of standardisation can have significant uses – and significant implications. But, when we think of standardisation in, for example, a data project to better understand supply chains, we might also be considering standards at the level of schema- the agreed way to combine lots of small atoms of data to build up a picture of some actions or phenomena we care about.

A standardised data schema can take many forms. In data exchange, we’re often not dealing with relational database schemas, but with schemas that allow us to share an extract from a database or system.

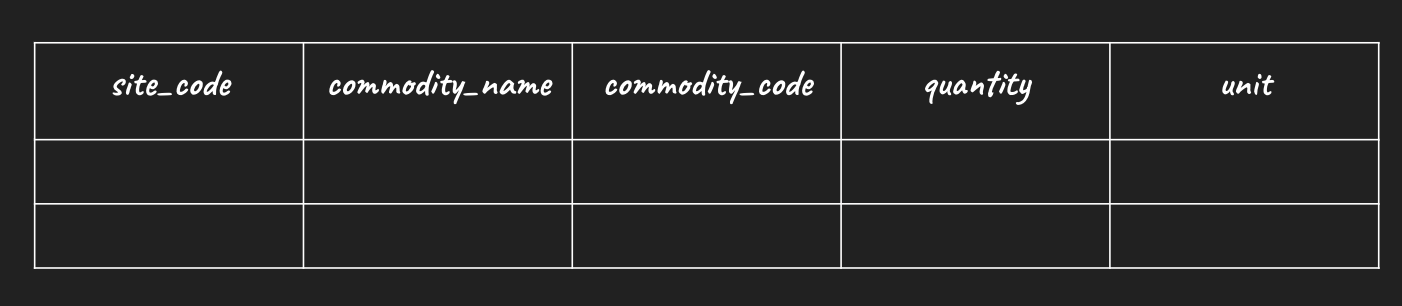

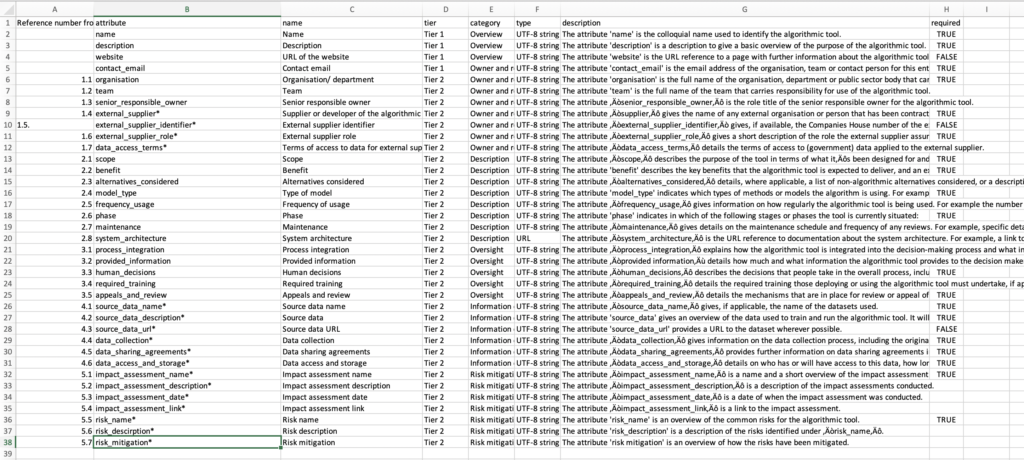

That extract might take the form of tabular data, where our schema can be thought of as the common header row in a spreadsheet accompanied by definitions for what should go in each column.

Or it might be a schema for JSON or XML data: where the schema may also describe hierarchical relationships between, say a company, its products, and their locations.

At a very simplified and practical level, a schema usually needs three things:

- Field names (or paths)

- Definition

- Validation rules

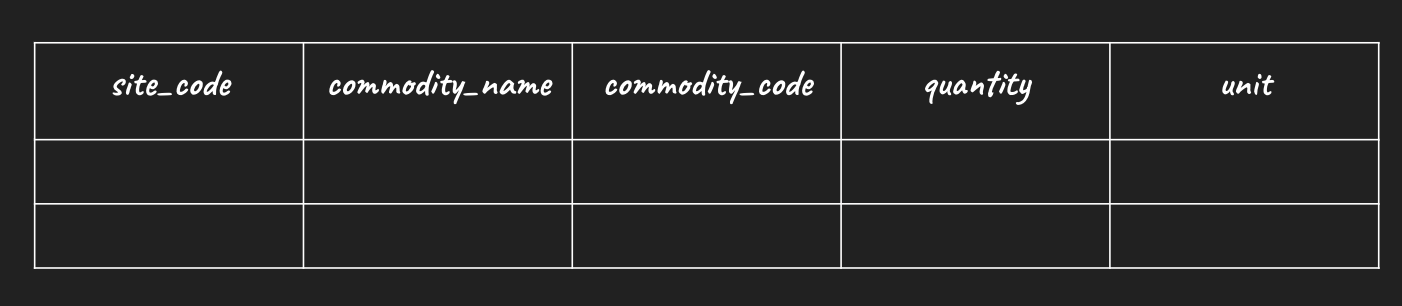

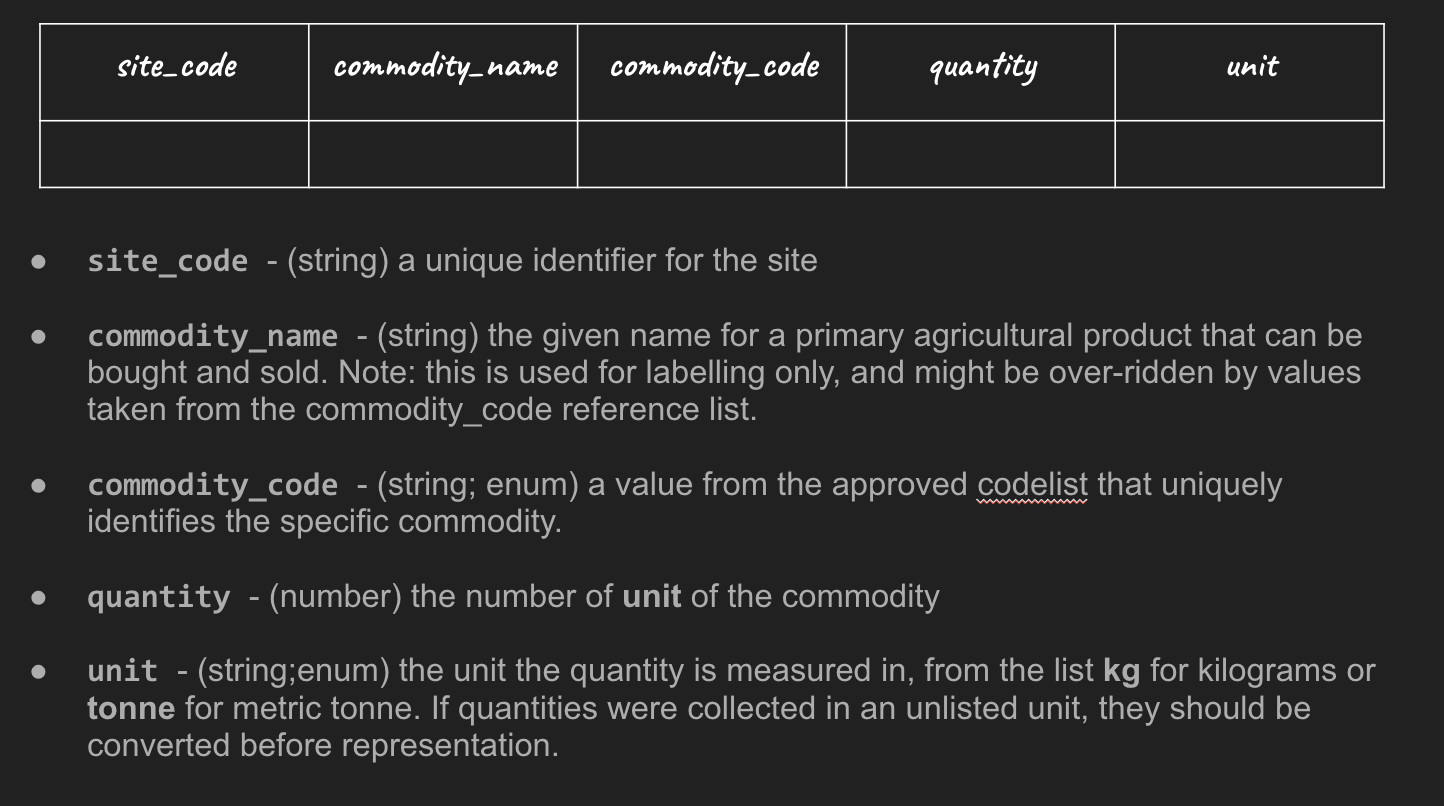

For example, we might agree that whenever we are recording the commodities produced at a given site we use the column names site_code commodity_name, commodity_code, quantity and unit.

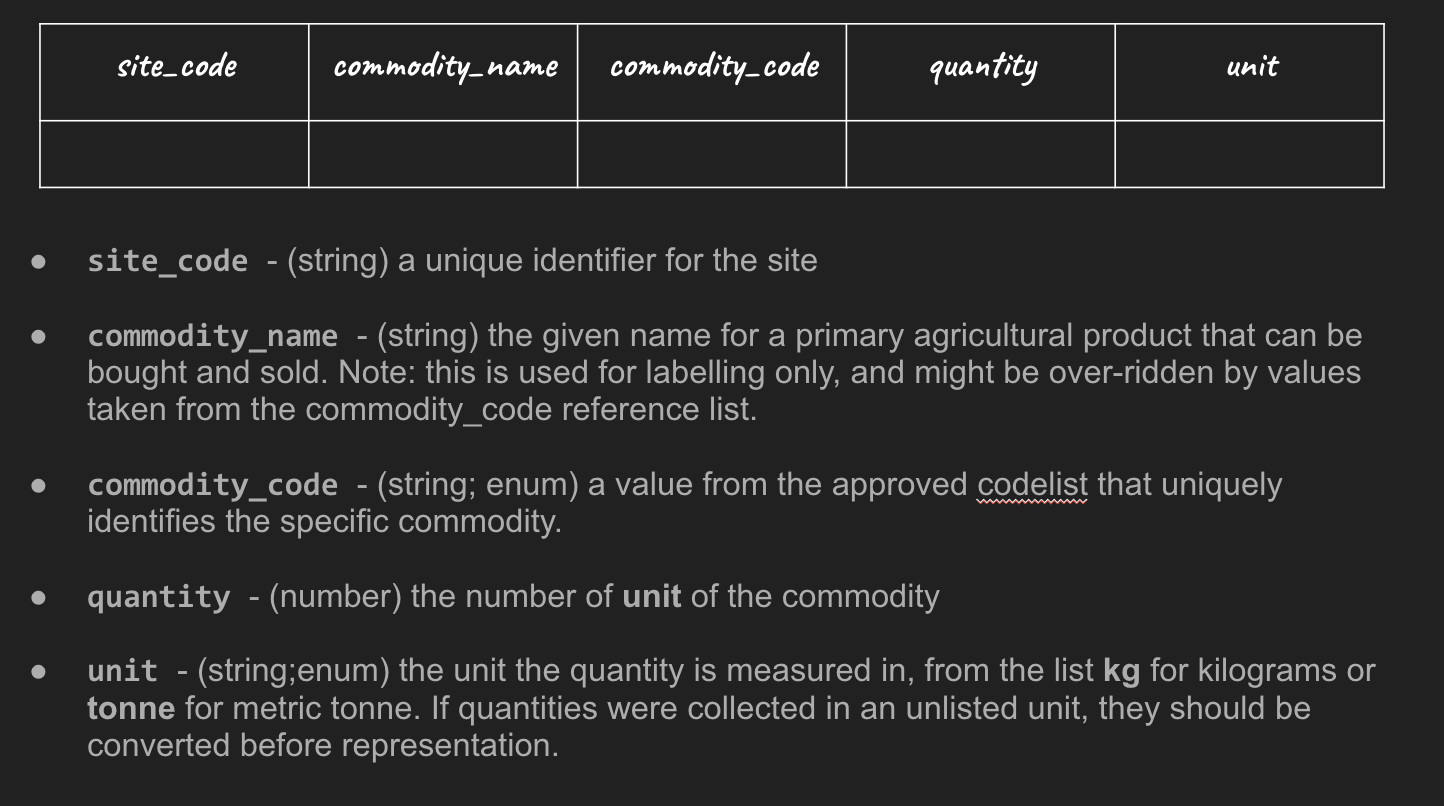

We then need human readable definitions for what counts as each. E.g:

And we need validation rules to say that if we find, for example, a non-number character in the quantity column – the data should be rejected – as it will be tricky for systems to process.

Note that three of these potential columns point us to another aspect of standardisation: codelists.

A codelist is a restricted set of reference values. You can see a number of varieties here:

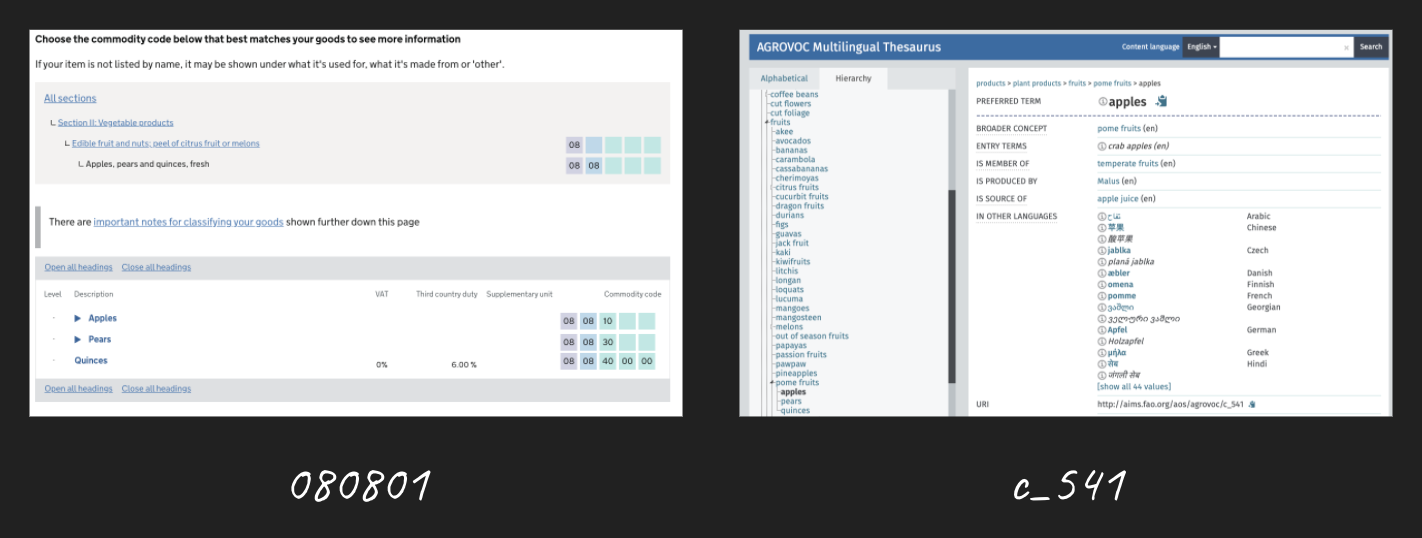

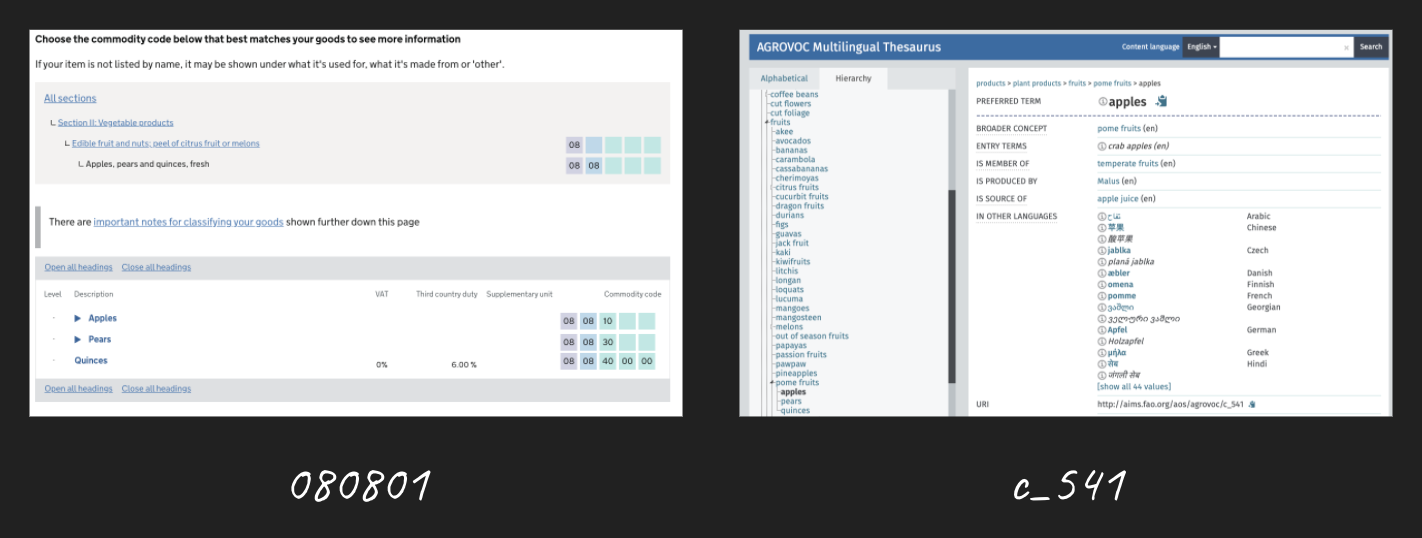

The commodity code is a conceptual codelist. In designing this hypothetical standard we need to decide about how to be sure apples are apples, and oranges are oranges. We could invent our own list of commodities, but often we would look to find an existing source.

We could, for example, use ‘080810’ taken from the World Custom Organisations Harmonised System codes

Or we could c_541 taken from AGROVOC – the FAO’s Agricultural Vocabulary.

The choice has a big impact: aligning us with export applications of the data standard, or perhaps more with agricultural science uses of the data.

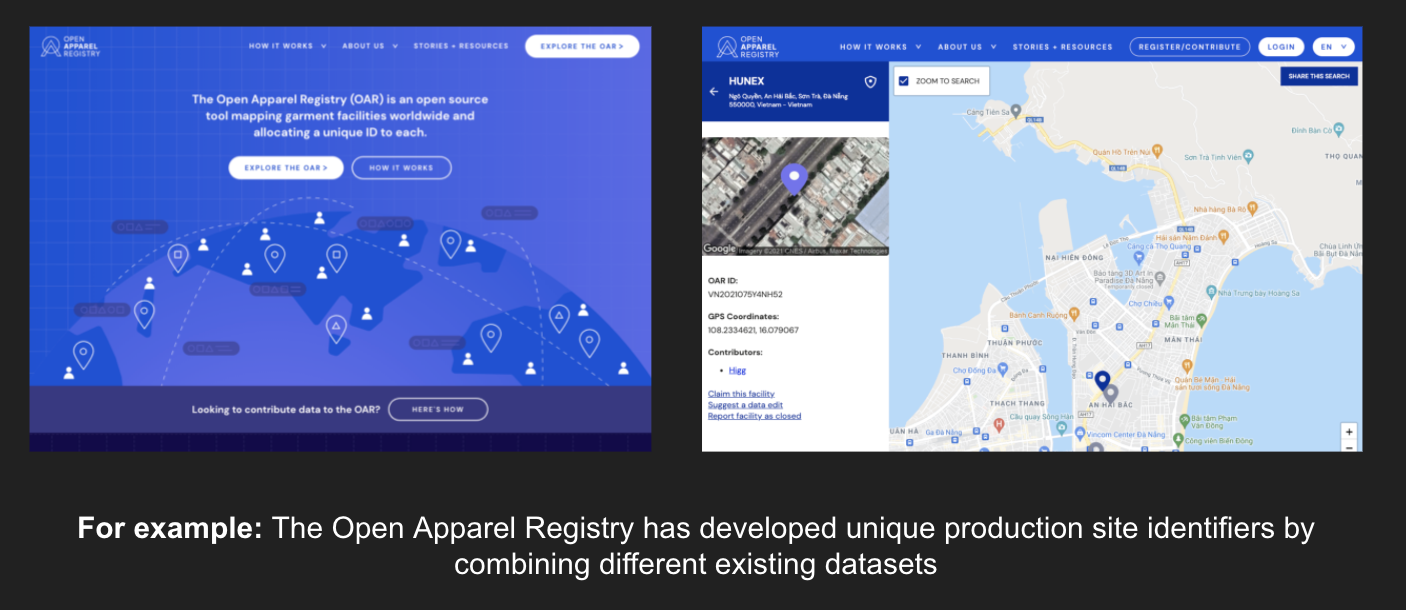

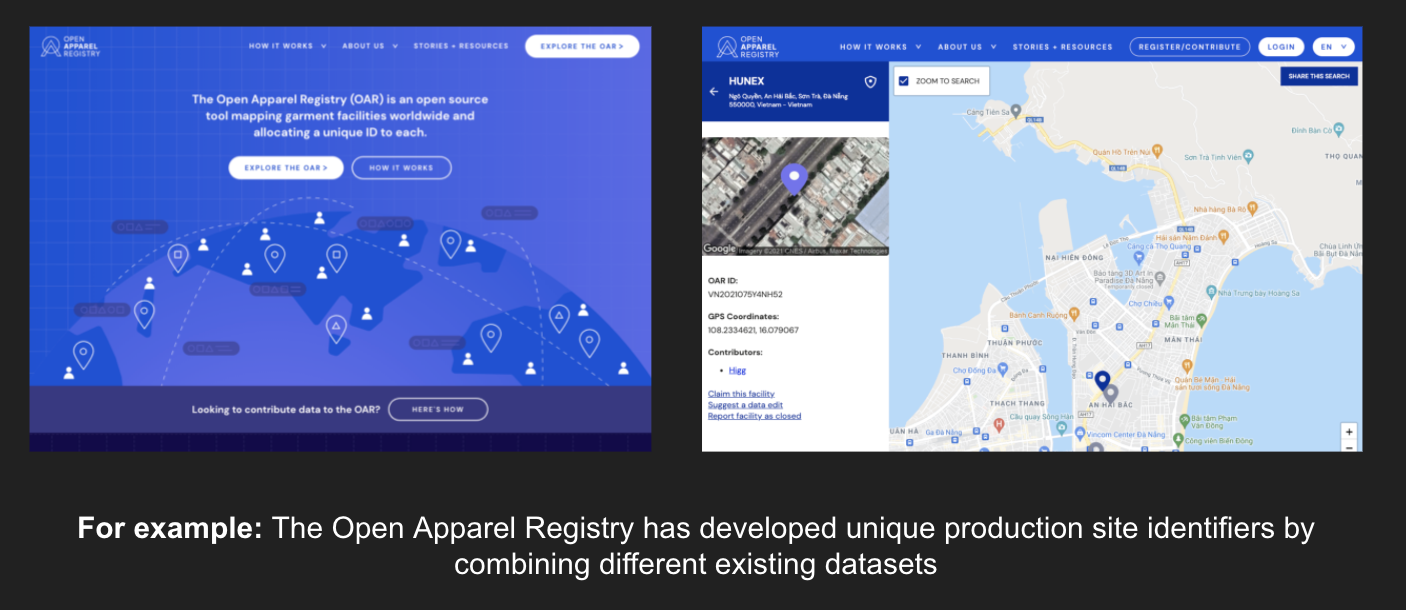

site_code, by contrast, is not about concepts – but about agreed identifiers for real-world entities, locations or institutions.

Without agreement across different dataset of how to refer to a farm, factory or other site, integrating data and data exchange can be complex: but maintaining these reference lists is also a big job, a potential point of centralisation and power, and an often neglected piece of data infrastructures.

Now – I could spend the rest of this talk digging deeper into just this small example – but let’s surface to make the broader points.

- Data standards are technical specifications of how to exchange data

The data should be collected in the way that makes the most sense at a local level (subject to ability to then fit into a standard) – and should be presented in the way that meets users needs. But when data is coming from many sources, and going to many destinations, a standard is a key tool of collaboration.

The standard is not the form.

The standard is not the report.

But, well designed, the standard is the powerful bit in the middle that ties together many different forms and sources of data, with many different reports, applications and data uses.

- Designing standards is a technical task

It needs an understanding of the systems you need to interface with.

- Designing standards goes beyond the technical tasks

It needs an awareness of the impact of each choice – each alignment – each definition and each validation rule.

There are a couple of critical dimensions to this: from thinking about whose knowledge is captured and shared through a standard, and who gains positions of power by being selected as the source of definitions and codelists.

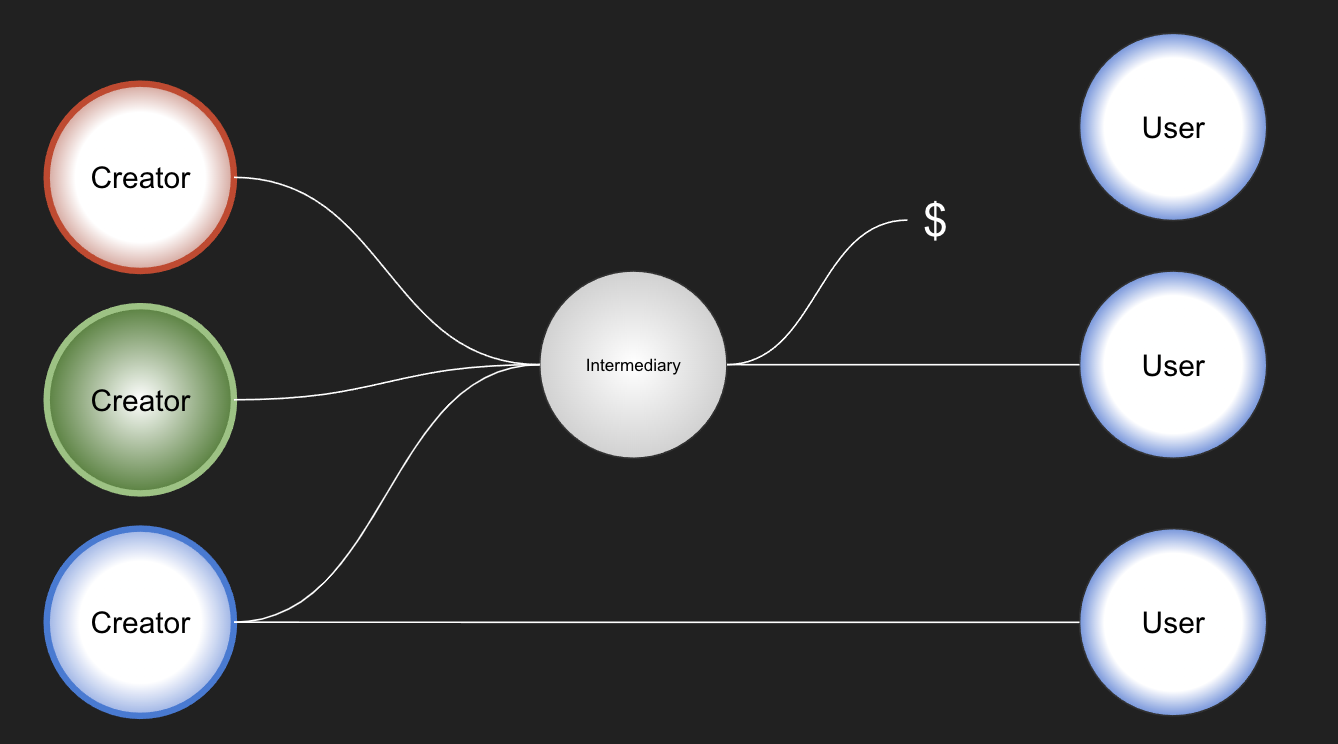

At a more practical level, I often use the following simple economic model to consider who bears the costs of making data interoperable:

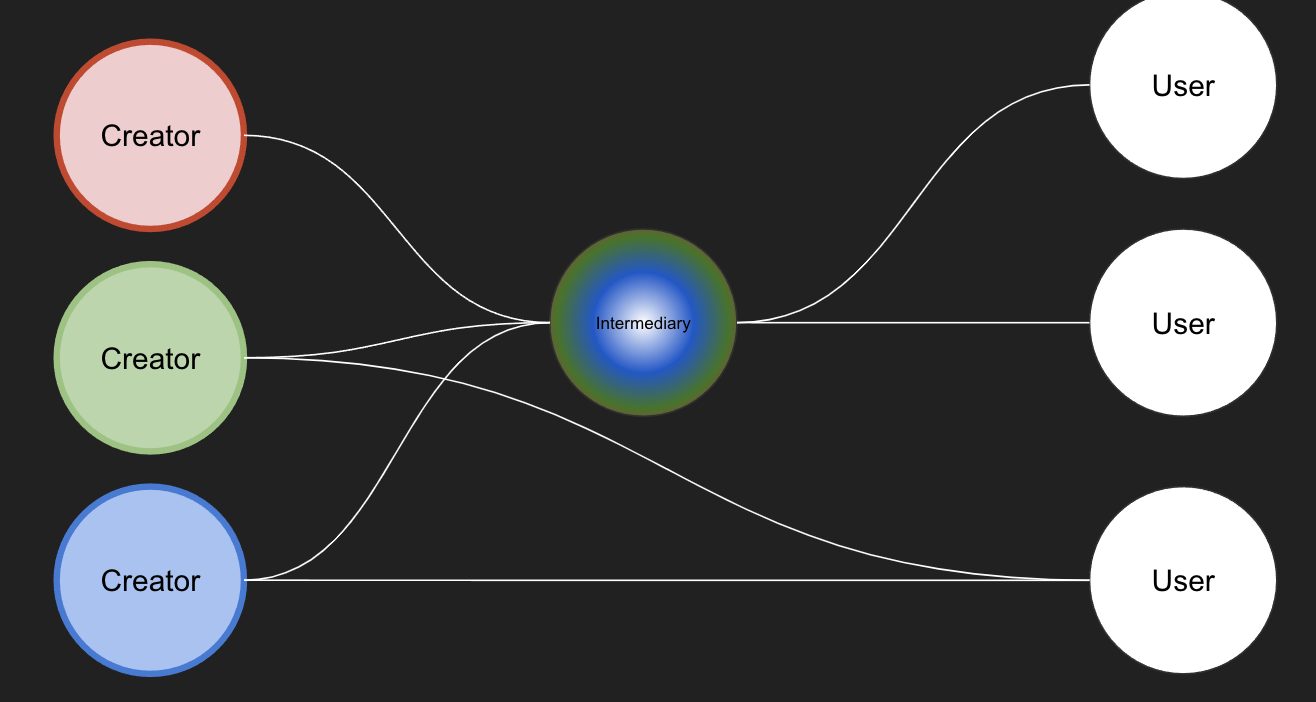

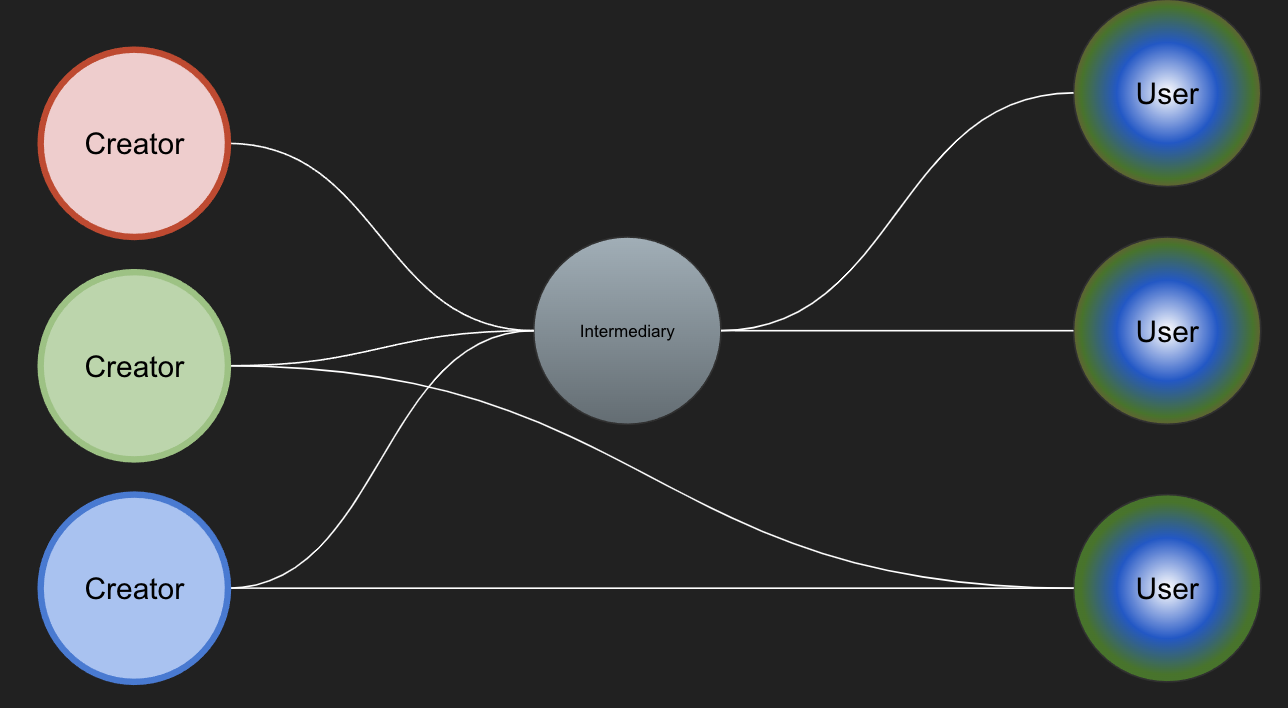

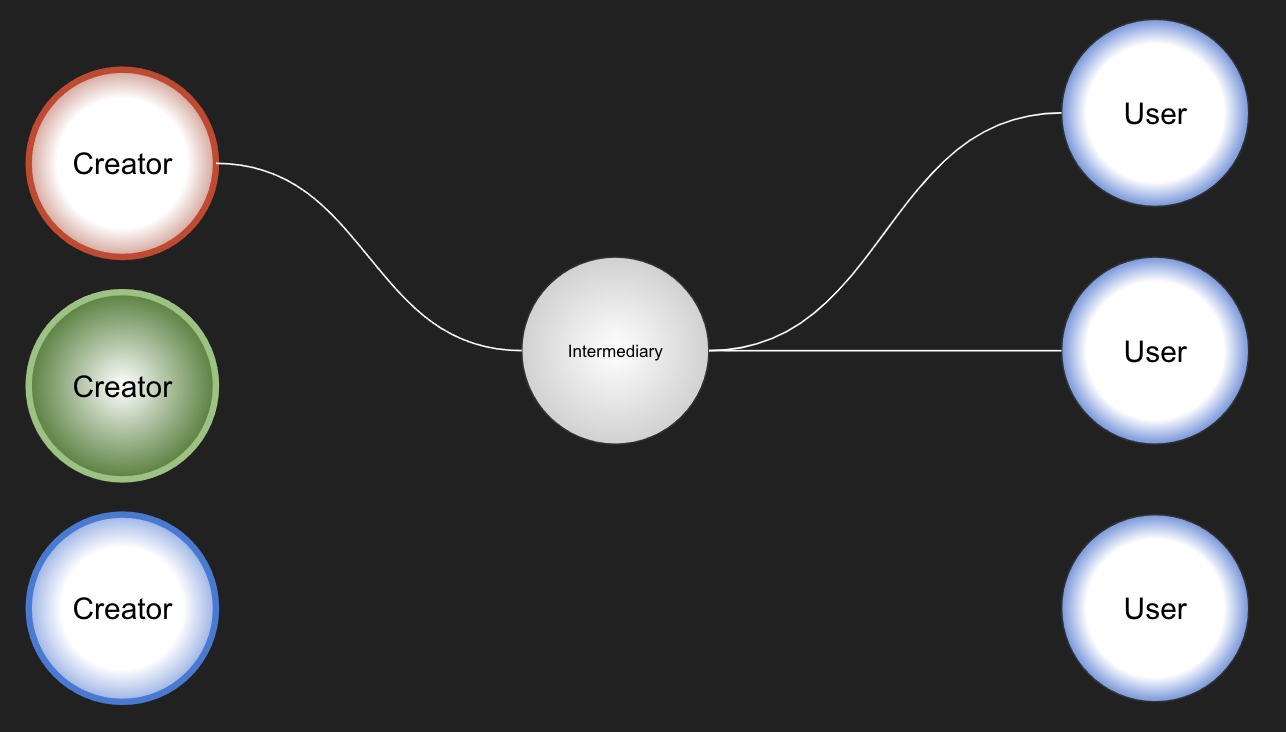

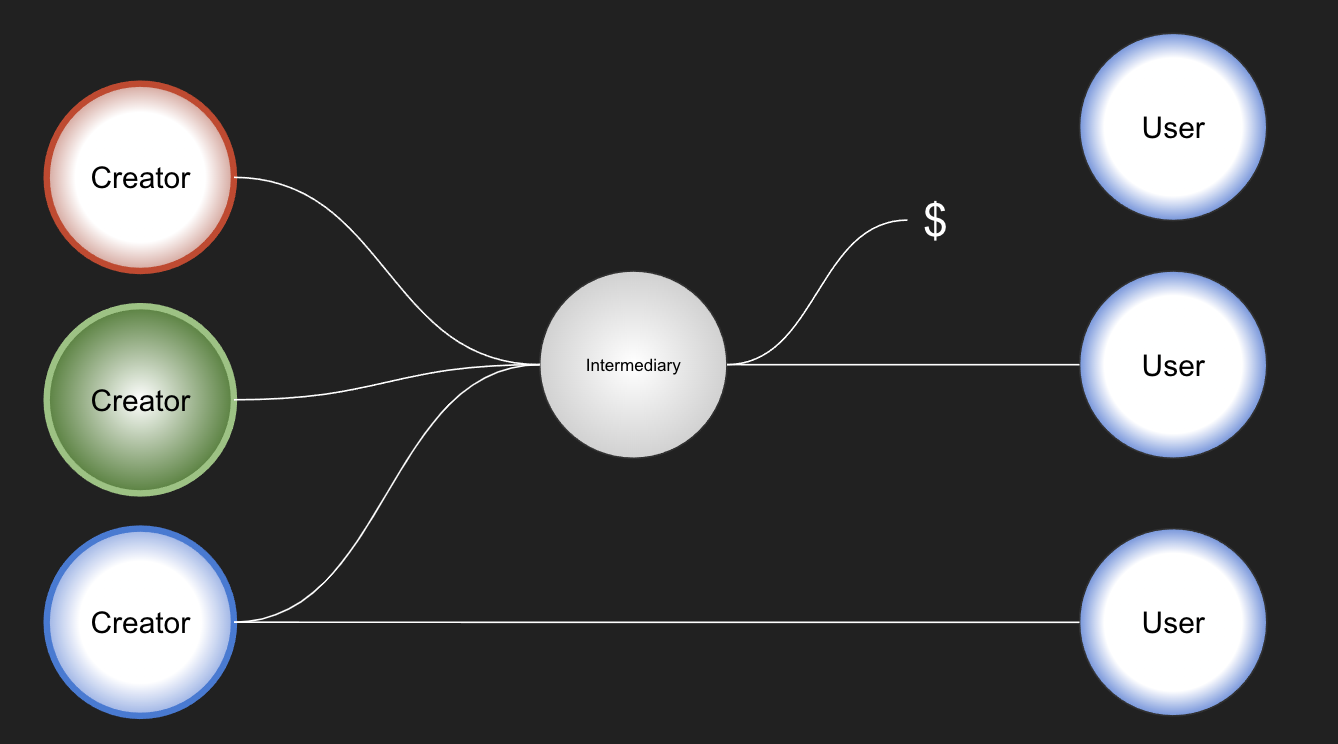

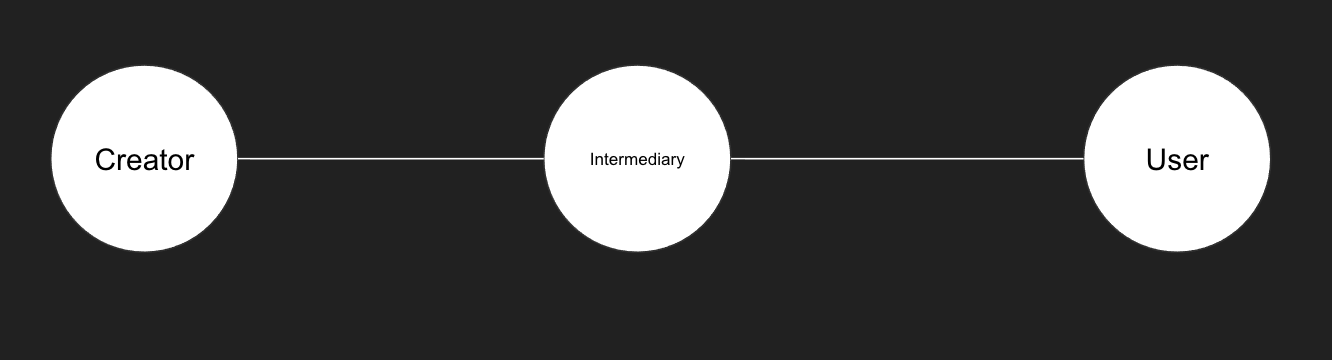

In any data exchange there is a creator, there may be an intermediary, and there is a data user.

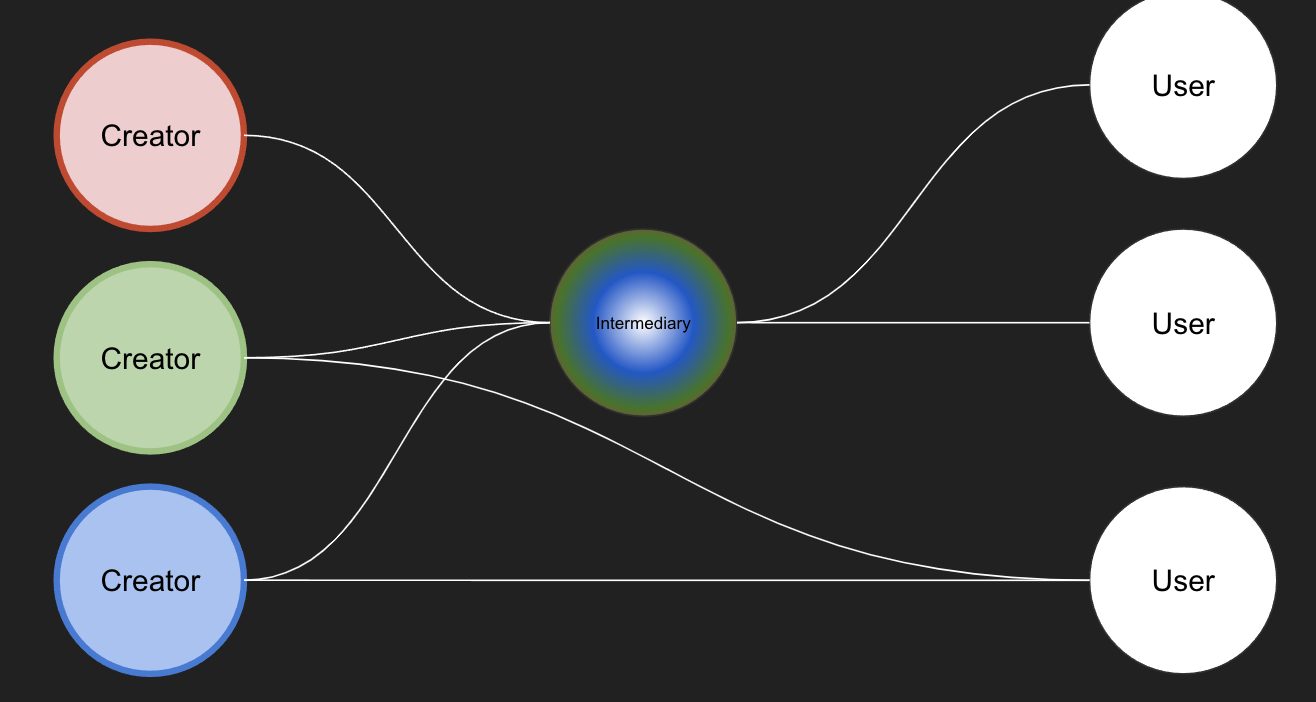

The real value of standards comes when you have multiple creators, multiple users, and potentially, multiple intermediaries.

If data isn’t standardised, either an intermediary needs to do lots of work cleaning up the data….

…or each user has all that work to do before they can spend any time on data use and analysis.

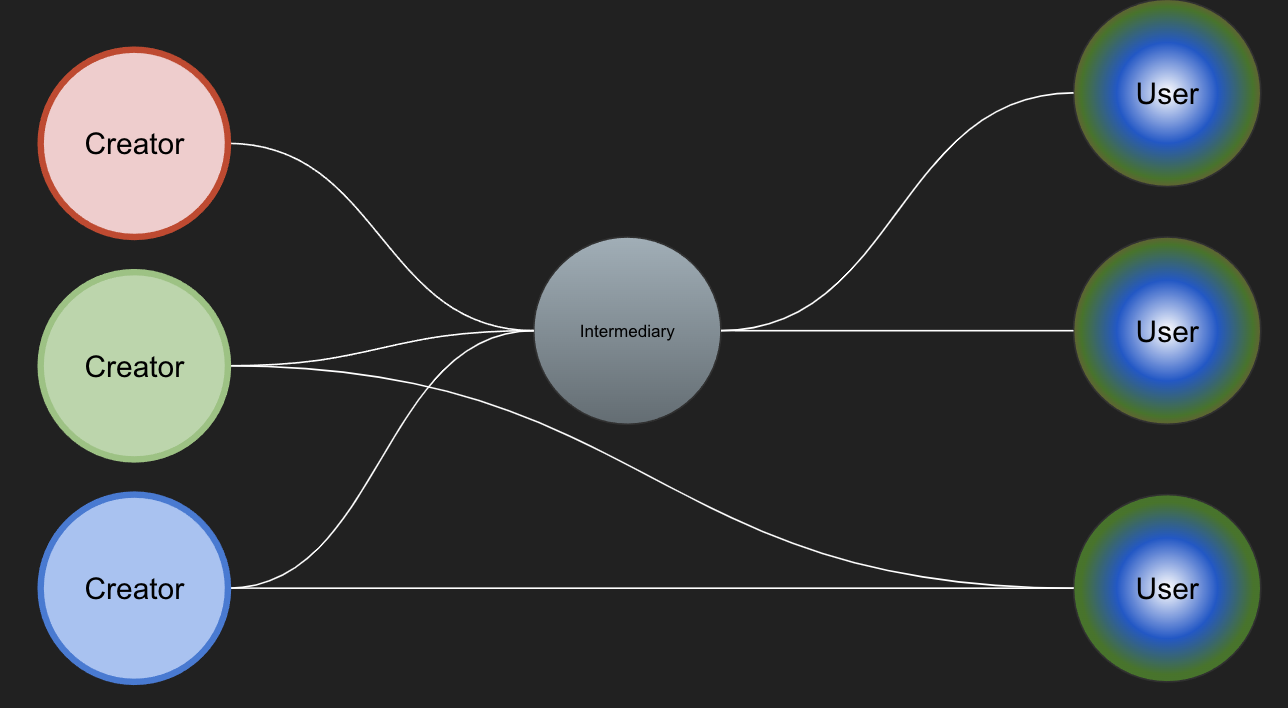

The design choices made in a standard distribute the labour of making data interoperable across the parties in a data ecosystem.

There may still be some work for users and intermediaries to do even after standardisation.

For example, if you make it too burdensome for creators to map their data to a standard, they may stop providing it altogether.

Or if you rely too much on intermediaries to clean up data, they may end up creating paywalls that limit use.

Or, in some cases, you may be relying on an exploitative ‘click-work’ market to clean data, that could have been better standardised at source.

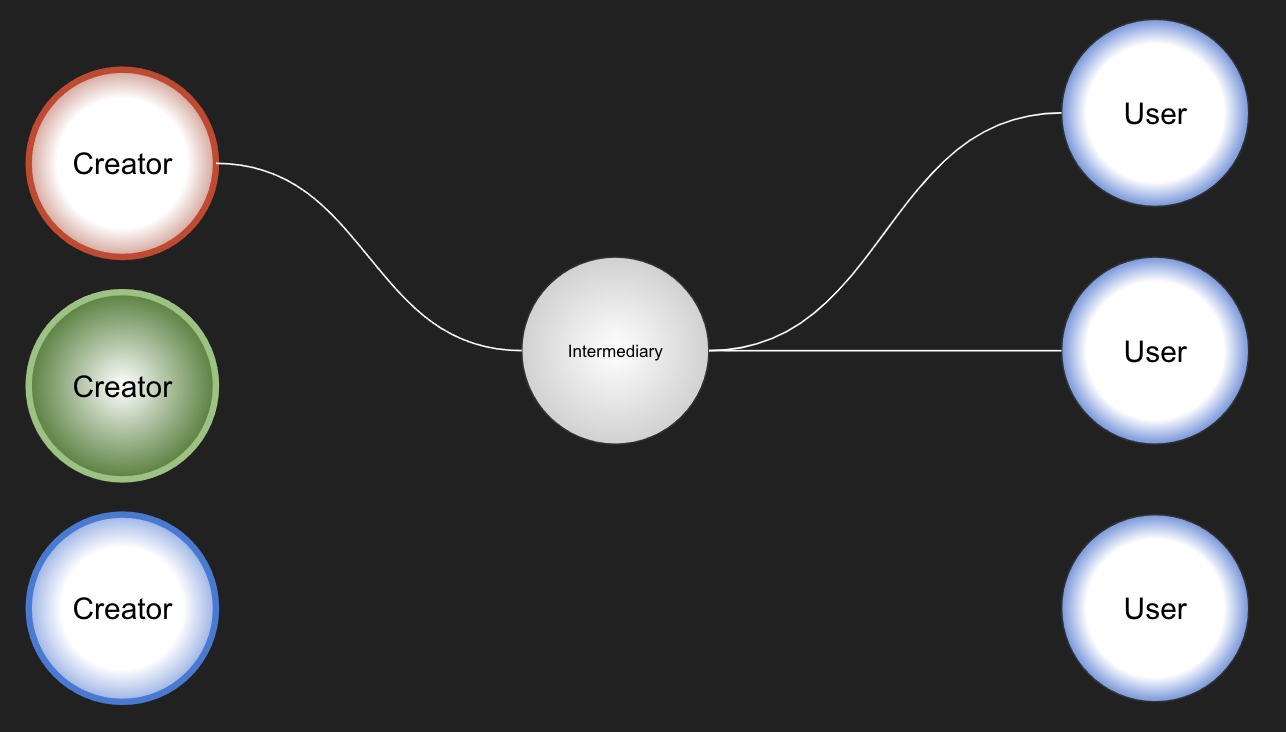

So – to work out where the labour of making data interoperable should and can be located involves more than technical design.

You need to think about the political incentives and levers to motivate data creators to go to the effort of standardising their data.

You need to think about the business or funding model of intermediaries.

And you need to understand the wide range of potential data users: considering carefully whose needs are served simply, and who will end up still having to carry out lots of additional data collection and cleaning before their use-cases are realised.

But, hoping I’ve not put you off with some of the complexity here, my fourth and final general point on standards is that:

4. Data standards could be a powerful tool for the projects you are working on.

And to talk about this, let’s turn to the twin concepts of ecosystem and infrastructure.

Data ecosystems

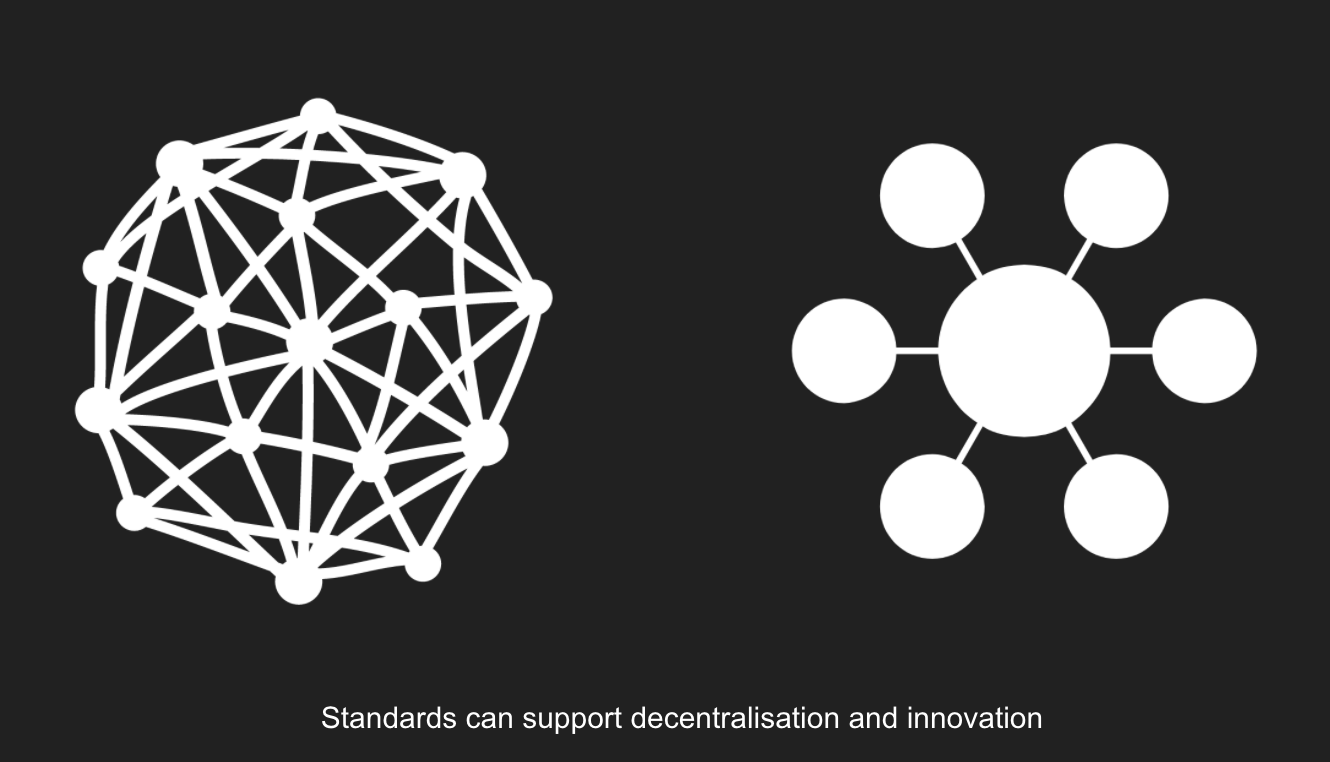

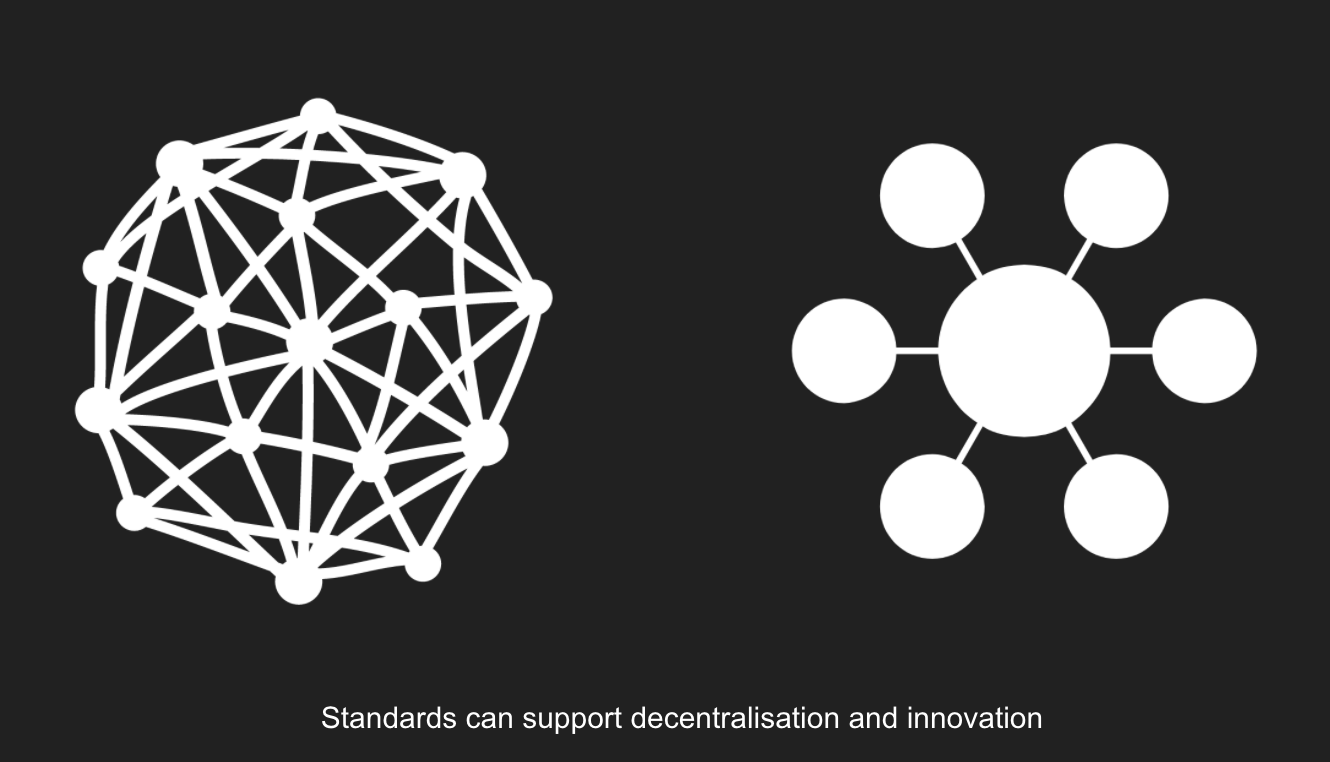

When the Internet and World Wide Web emerged, they were designed as distributed systems. Over recent decades, we’ve come to experience a web that is much more based around dominant platforms and applications.

This ‘application thinking’ can also pervade development programmes – where, when thinking about problems that would benefit from better data exchange, funders might leap to building a centralised platform or application to gather data.

But – this ‘build it and they will come’ approach has some significant problems: not least that it only scales so far, it creates single points of failure, and risks commercial capture of data flows.

By contrast, an open standard can describe the data we want to see better shared, and then encourage autonomous parties to create applications, tools, support and analysis on top of the standard.

It can also give data creators and users much greater freedom to build data processes around their needs, rather than being constrained by the features of a central platform.

In early open data thinking, this was referred to as the model of ‘let many flowers bloom’, and as ‘publish once, use everywhere’ – but over time we’ve seen that, just like natural ecosystems – creating a thriving data ecosystem can require more intentional and ongoing action.

Just like their natural counterparts, data ecosystems are complex, dynamic, and equilibrium can be hard to reach and fragile. Keystone species can support an ecosystems growth; whilst a local resource drought harming some key actors could lead to a cascading ecosystem collapse.

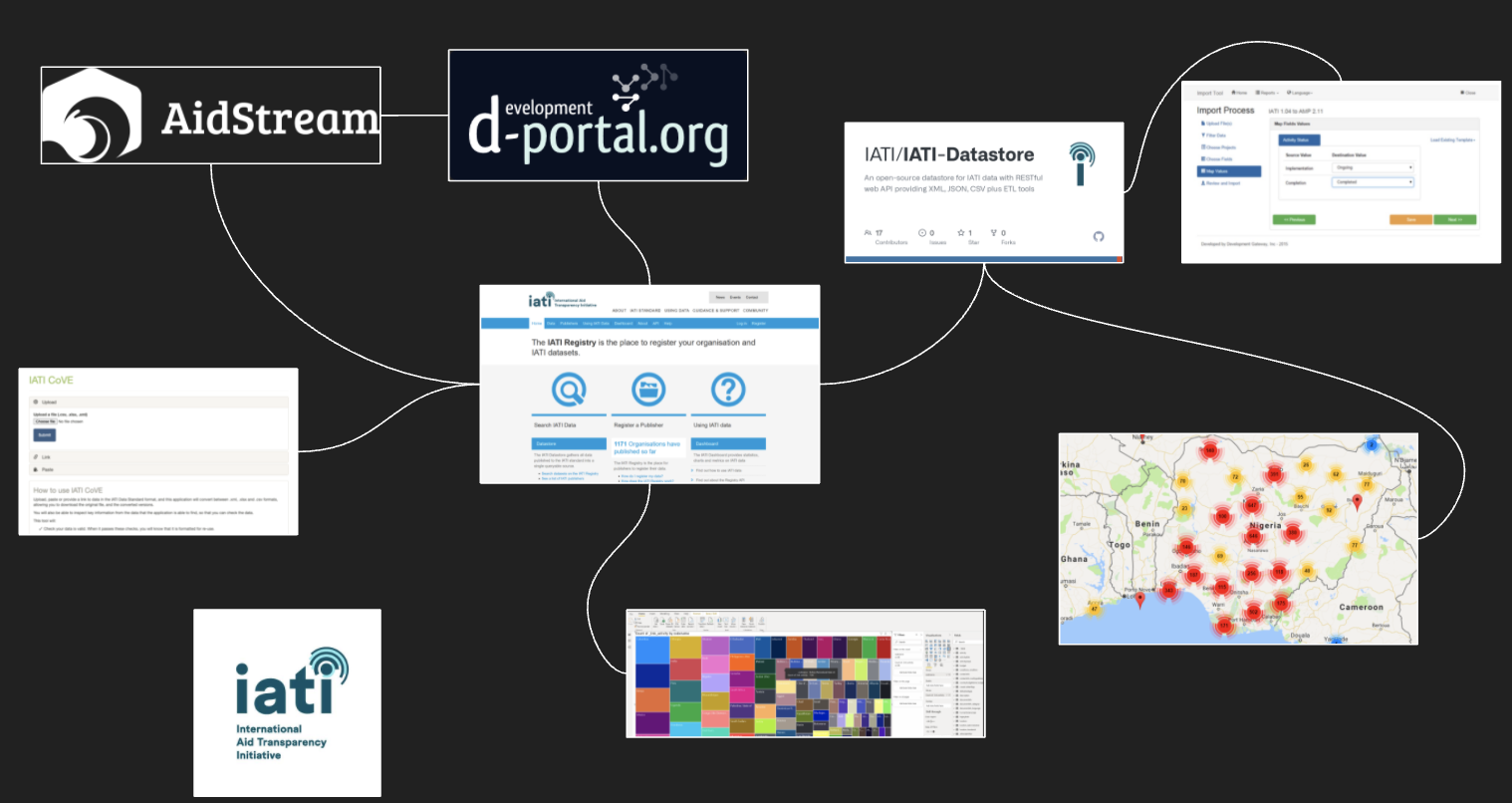

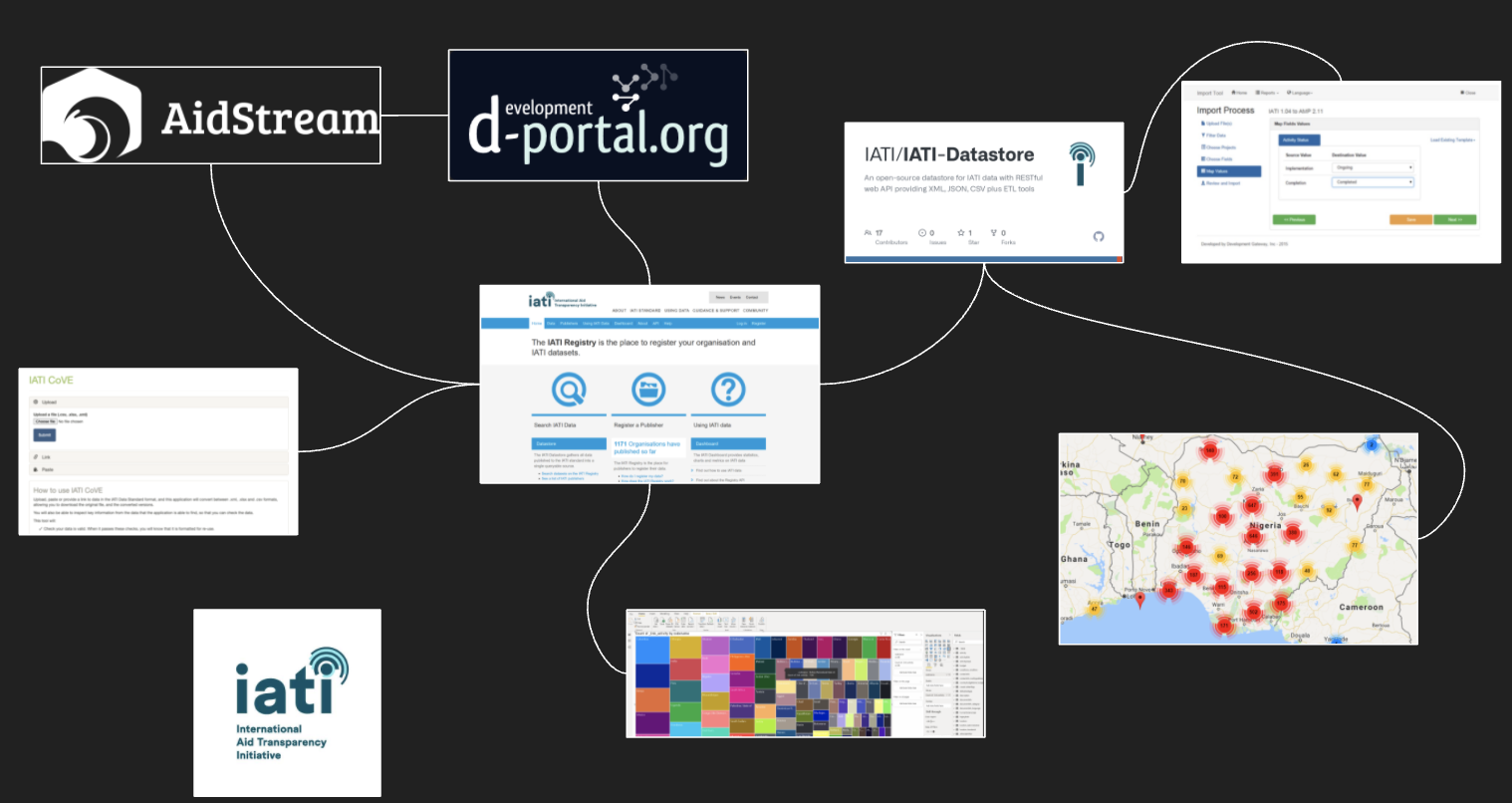

To give a more concrete example – a data ecosystem around the International Aid Transparency Initiative has grown up over the last decade – with hundreds of aid donors big and small sharing data on their projects in a common data format: the IATI Standard. ‘Keystone species’ such as D-Portal, which visualises the collected data, have helped create an instant feedback loop for data publishers to ‘see’ their data, whilst behind the scenes, a Datastore and API layer feeds all sorts of specific research and analysis projects, and operational systems – that one their own would have had little leverage to convince data publishers to send them standardised data.

However, elements of this ecosystem are fragile: much data enters through a single tool – AidStream – which over time has come to be the tool of choice for many NGOs and if unavailable would diminish the freshness of data. Many users accessing data rely on ‘the datastore’ which aggregates published IATI files and acts as an intermediary so users don’t need to download data from hundreds of different publishers. If the datastore is down, many usage applications may fail. Recently, when new versions of the official datastore hit technical trouble, an old open source software was brought back initially by volunteers.

Ultimately, this data ecosystem is more resilient than it would otherwise be because it’s built on an open standard. Even if the data entry tool, or datastore become inaccessible, new tools can be rapidly plugged in. But that they will can’t just be taken for granted: data ecosystems need careful management just as natural ones do.

The biggest point I want to highlight here is a design one. Instead of designing platforms and applications, it’s possible to design for, and work towards, thriving data ecosystems.

That can require a different approach: building partnerships with all those who might have a shared interested in the kind of data you are dealing with, building political commitments to share data, investing in the technical work of standard development, and fostering ecosystem players through grants, engagement and support.

Building data ecosystems through standardisation can crowd-in investment: having a significant multiplier effect.

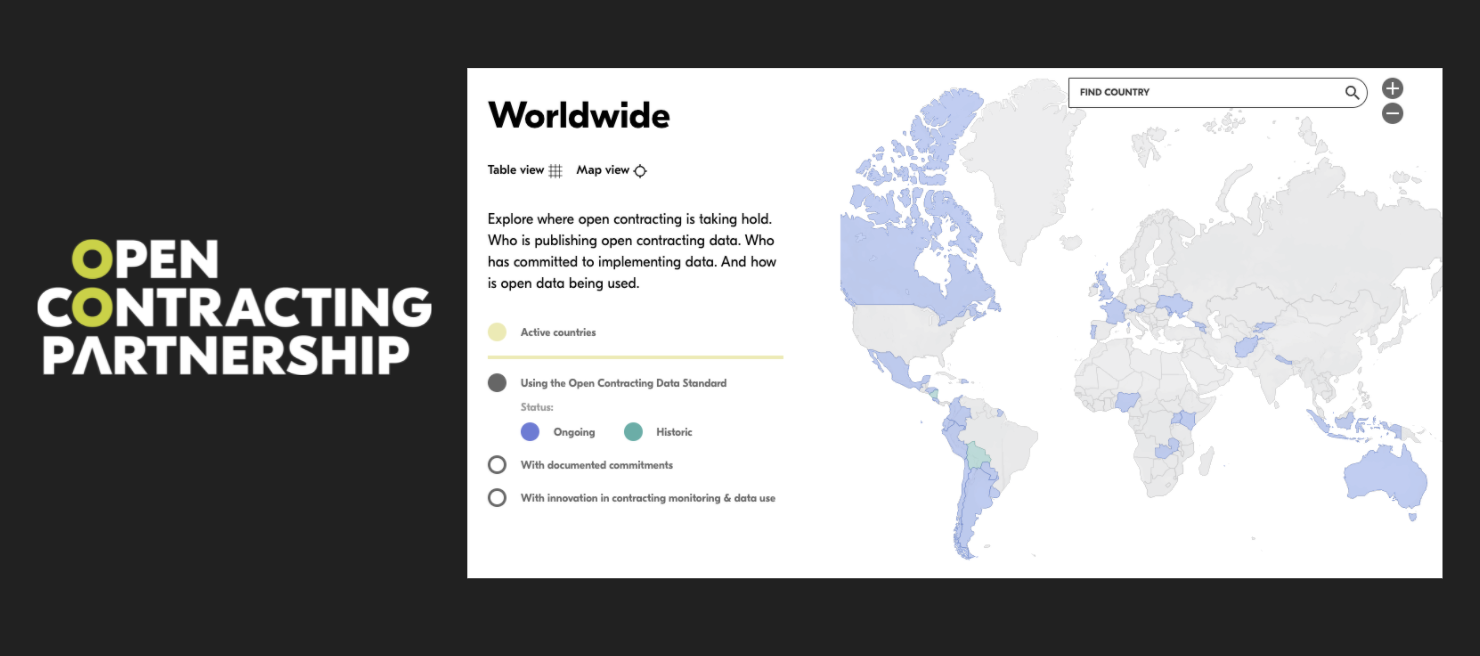

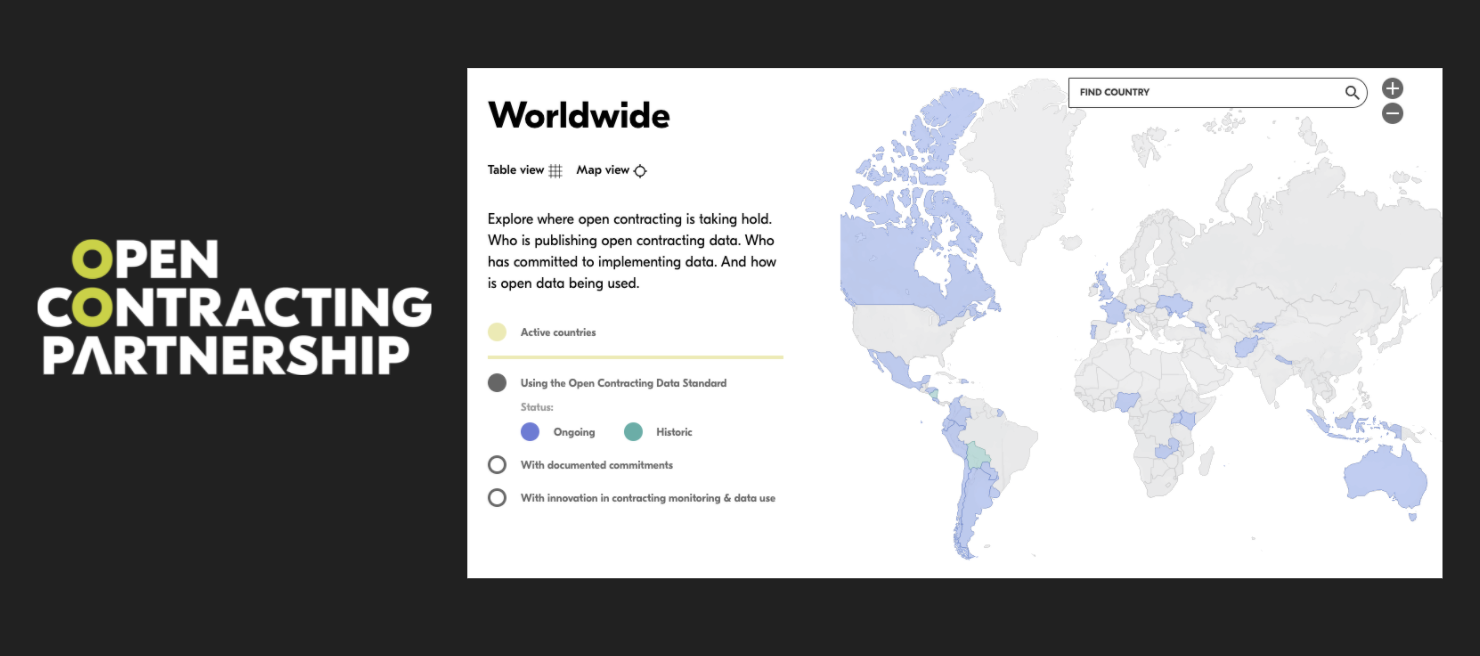

For example, most of the implementations of the Open Contracting Data Standard have not been funded by the Open Contracting Partnership which stewards it’s design – yet they incorporate particular ideas the standard encodes, such as providing linked information on tender and contract award, and providing clear identifiers to the companies involved in procurement.

For the low millions of dollars invested in maintaining OCDS since it’s first half-million dollar year-long development cycle – many many more millions from a myriad of sources have gone into building bespoke and re-usable tools, supported by for-profit and non-profit business models right across the world.

And innovation has come from the edges, such as the adoption of the standard in Ukraine’s corruption-busting e-procurement system, or the creation of tools using the standard to analyse paper-based procurement systems in Nigeria.

As a side note here – I’m not necessarily saying ‘build a standard’: often times, the standards you need might almost be there already. Investing in standardisation can be a process of adaptation and engagement to improve what already exists.

And whilst I’m about to talk a bit more about some of the technical components that make standards for open data work well, my own experience helping to develop the ecosystem around public procurement transparency with the Open Contracting Data Standard has underscored for me the vitally important human community building element of data ecosystem building. This includes supporting governments and building their confidence to map their data into a common standard: walking the narrow line between making data inter-operable at a global level, and responding to the diverse situations in terms of legacy data systems, relevant regulation and political will different that countries found themselves in.

Infrastructures

I said earlier that it is productive to pair the concept of an ecosystem with that of an infrastructure. If ecosystems contain components adapted to each niche: an infrastructure, in data terms, is something shared across all sites of action. We’re familiar with physical infrastructures like the road and rail networks, or energy grid. These can provide useful analogies for thinking about data infrastructure. Well managed, data infrastructures are the underlying public good which enable an ecosystems to thrive.

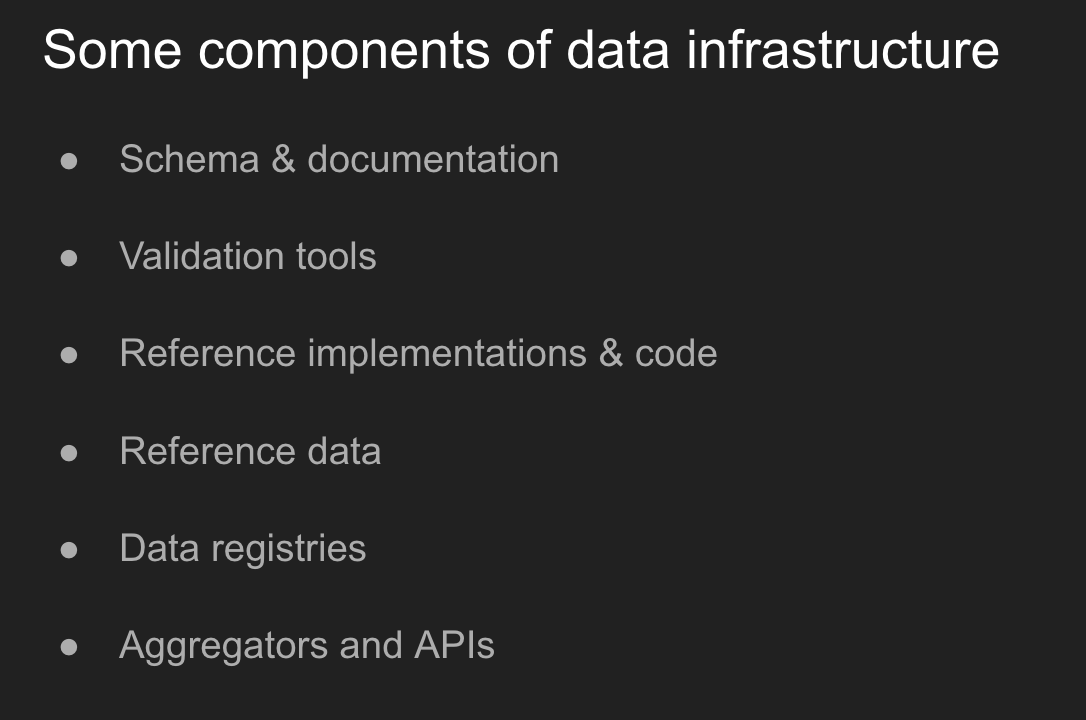

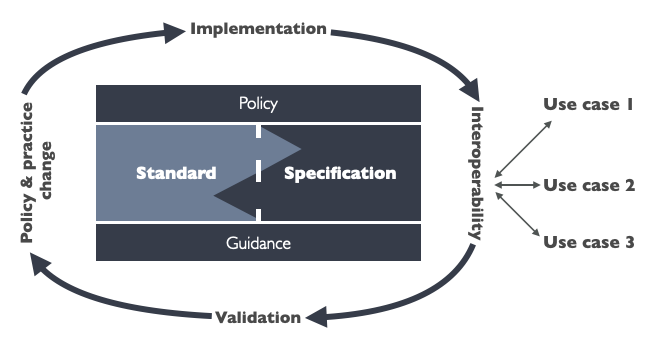

In practice, the data infrastructure of a standard can involve a number of components:

- There’s the schema itself and it’s documentation.

- There might be validation tools that tell you if a dataset conforms with the standard or not.

- There might be reference implementations and examples to work from.

- And there might be data registries, or data aggregators and APIs that make it easier to get a corpus of standardised data.

Just like our physical infrastructure, there are choices to make in a data infrastructure over whose needs it will be designed around, how it will be funded, and how it will be owned and maintained.

For example, if the data ecosystem you are working with involves sensitive data, you may find you need to pair an open standard with a more centralised infrastructure for data exchange, in which standardised data is available through a clearing-house which manages who has access or not to the data, or which assures anonymisation and privacy protecting practices have taken place.

By contrast, a data standard to support bi-lateral data exchange along a supply chain may need a good data validator tool to be maintained and provided for public access, but may have little need for a central datastore.

There’s a lot more written on the concept of data infrastructures: both drawing on technology literatures, and some rich work on the economics of infrastructure.

But before sharing some closing thoughts, I want to turn briefly to thinking about ‘data institutions’ – the organisational arrangements that can make infrastructures and ecosystems more stable and effective – and that can support cooperation where cooperation works best, and create the foundations for competition where competition is beneficial.

Institutions

A data standard is only a standard if it achieves a level of adoption and use. And securing that requires trust.

It requires those who might building systems that will work with the standard to be able to trust that the standard is well managed, and has robust governance. It requires users of schema and codelists to trust that they will remain open and free for use – rather than starting open and then later enclosed like the bait-and-switch that we’ve seen with many online platforms. And it requires leadership committing to adopting a standard to trust that the promises made for what it will do can be delivered.

Behind many standards and their associated infrastructures – you will find carefully designed organisational structures and institutions.

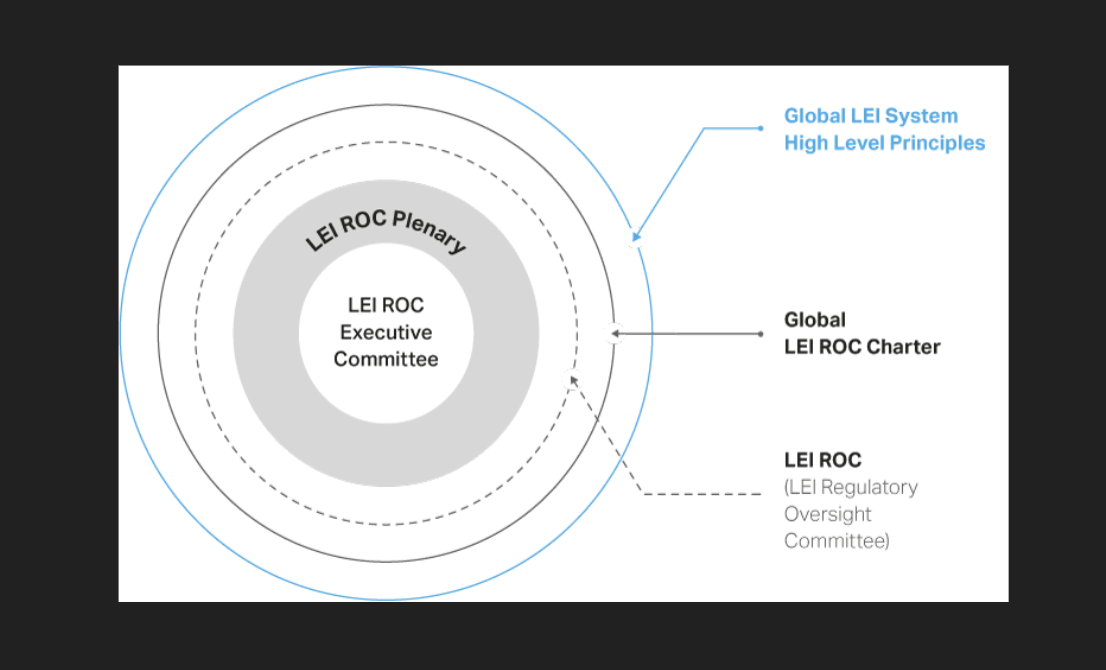

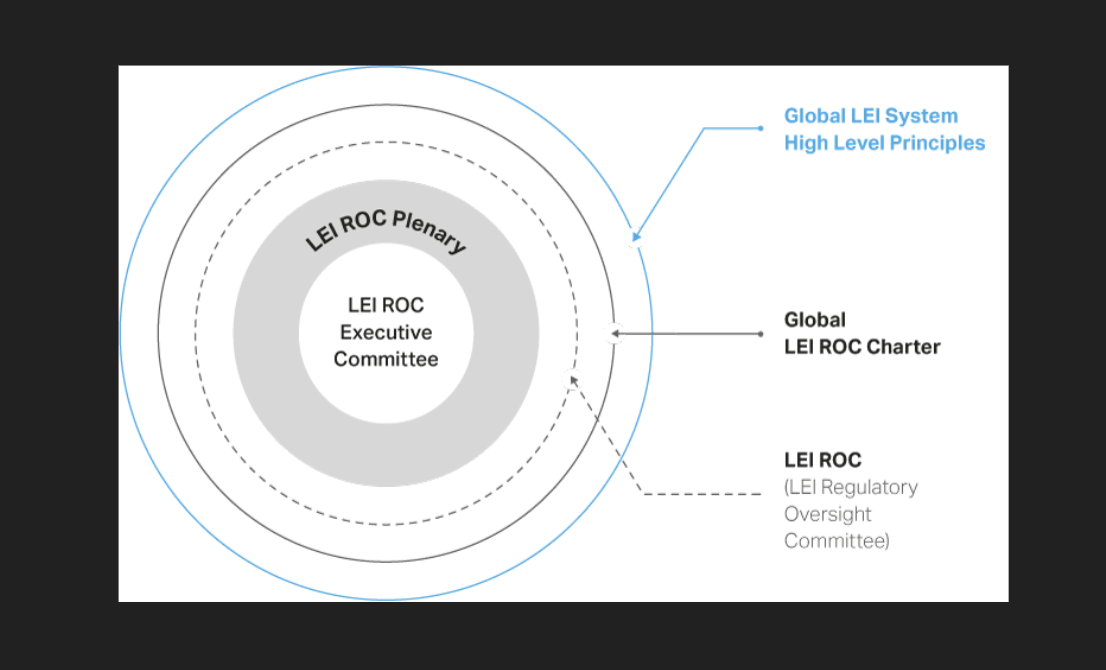

For example, the Global Legal Entity Identifier – designed to identify counter-parties in financial transactions – and avoid the kind of contagion of the 2008 financial crash, has layers of international governance to support a core infrastructure and policies for data standards and management, paired with licensed ‘Local Operating Units’ who can take a more entrepreneurial approach to registering companies for identifiers and verifying their identities.

The LEI standard itself has been taken through ISO committees to deliver a standard that is likely to secure adoption from enterprise users.

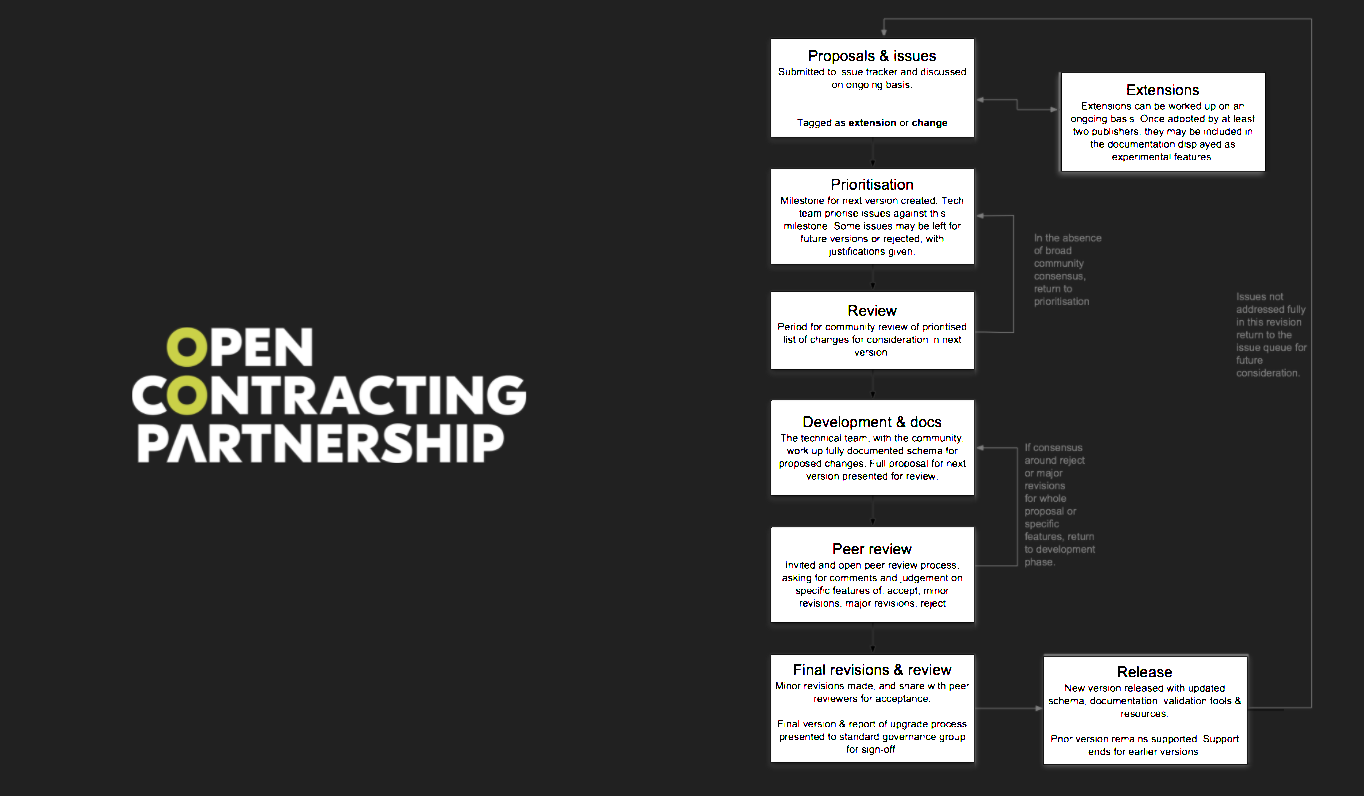

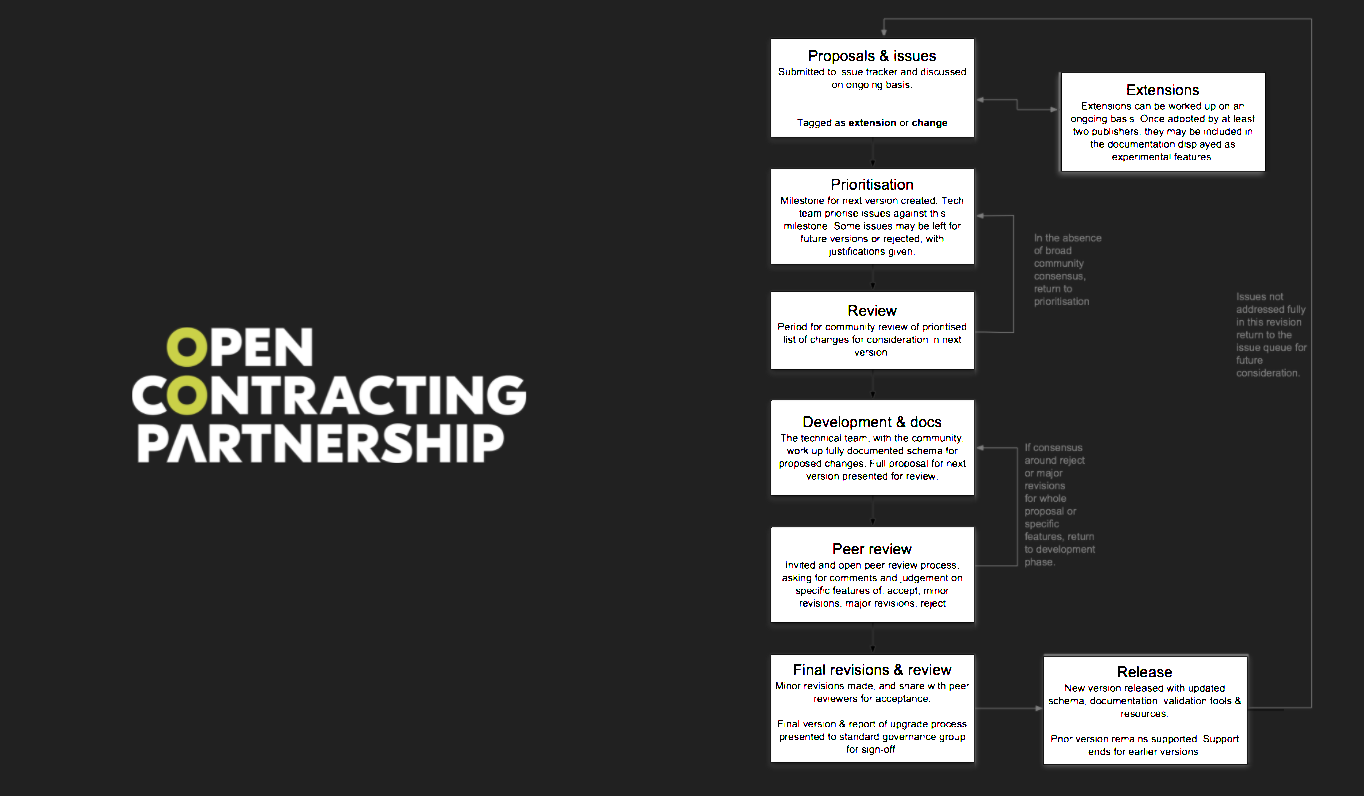

By contrast, the Open Contracting Data Standard I mentioned earlier is stewarded by an independent non-profit,

However, OCDS – seeking as I would argue it should – to disrupt some of the current procurement technology landscape – has not taken a formal standards body route – where there is a risk that well resourced incumbents would water down the vision within the standard. Instead, the OCDS team have developed a set of open governance processes for changes to the standard that aim to make sure it retains trust from government, civil society and private sector stakeholders, whilst also retaining some degree of agility.

We’ve seen over the last decade that standards and software tools alone are not enough: they need institutional homes, and multi-disciplinary teams who can provide the ongoing support that technical maintenance work, with stakeholder engagement, and strategic focus on the kinds of change the standards were developed to deliver.

If you are sponsoring data standards development work that’s aiming for scale, are you thinking about the long-term institutional home that will sustain it?

If you’re not directly developing standards, but the data that matters to you is shaped by existing data standardisation, I’d also encourage you to ask: who is standing up for the public interest and the needs of our stakeholders in the standardisation process?

For example, over the last few weeks we’ve heard how a key mechanism to meet the goals of the COP26 Climate Conference will be in the actions of finance and investment – and a raft of new standards, many likely backed by technical data standards – are emerging for corporate Environmental, Social and Governance reporting.

There are relatively few groups out there like ECOS, the NGO network engaging in technical standards committees to champion sustainability interests. I’ve struggled to locate any working specifically on data standards. Yet, in the current global system of ‘voluntary standardisation’, standards get defined by those who can afford to follow the meetings and discussions and turn-up. Too often, that restricts those shaping standards to corporate and developed government interests alone.

If we are to have a world of technical and data standards that supports social change, we need more support for the social change voices in the room.

Closing reflections & challenges

As I was preparing this talk, I looked back at The State of Open Data – the book I worked on with IDRC a few years ago to review how open data ecosystems had developed across a wide range of sectors. One of things that struck me when editing the collection was the significant difference between how far different sectors have developed effective ecosystems for standardised, generative, and solution-focussed, data sharing.

Whilst there are some great examples out there of data standards impacting policy, supporting smart data sharing and analysis, and fostering innovation – there are many places where we see dominant private platforms and data ecosystems developing that do not seem to serve the public interest – including, I’d suggest (although this is not my field of expertise) in a number of areas of agriculture.

So I asked myself why? What stops us building effective open standards? I have six closing observations, and in that, challenges, to share.

(1) Underinvestment

Data standards are not, in the scheme of things, expensive to develop: but neither is the cost zero – particularly if we want to take an inclusive path to standard development.

We consistently underinvest in public infrastructure, digital public infrastructure even more so. Supporting standards doesn’t deliver shiny apps straight away – but it can prepare the ground for them to flourish.

(2) Stopping short of version 2

How many of you are using Version 1.0 of a software package? Chances are most of the software you are using today has been almost entirely rewritten many times: each time building on the learning from the last version, and introducing new ideas to make it fit better with a changing digital world. But, many standards get stuck at 1.0. Funders and policy champions are reluctant to invest in iterations beyond a standard’s launch.

Managing versioning of data schema can involve some added complexity over versioning software – but so many opportunities are lost by a funding tendency to see standards work as done when the first version is released, rather than to plan for the ‘second curve’ of development.

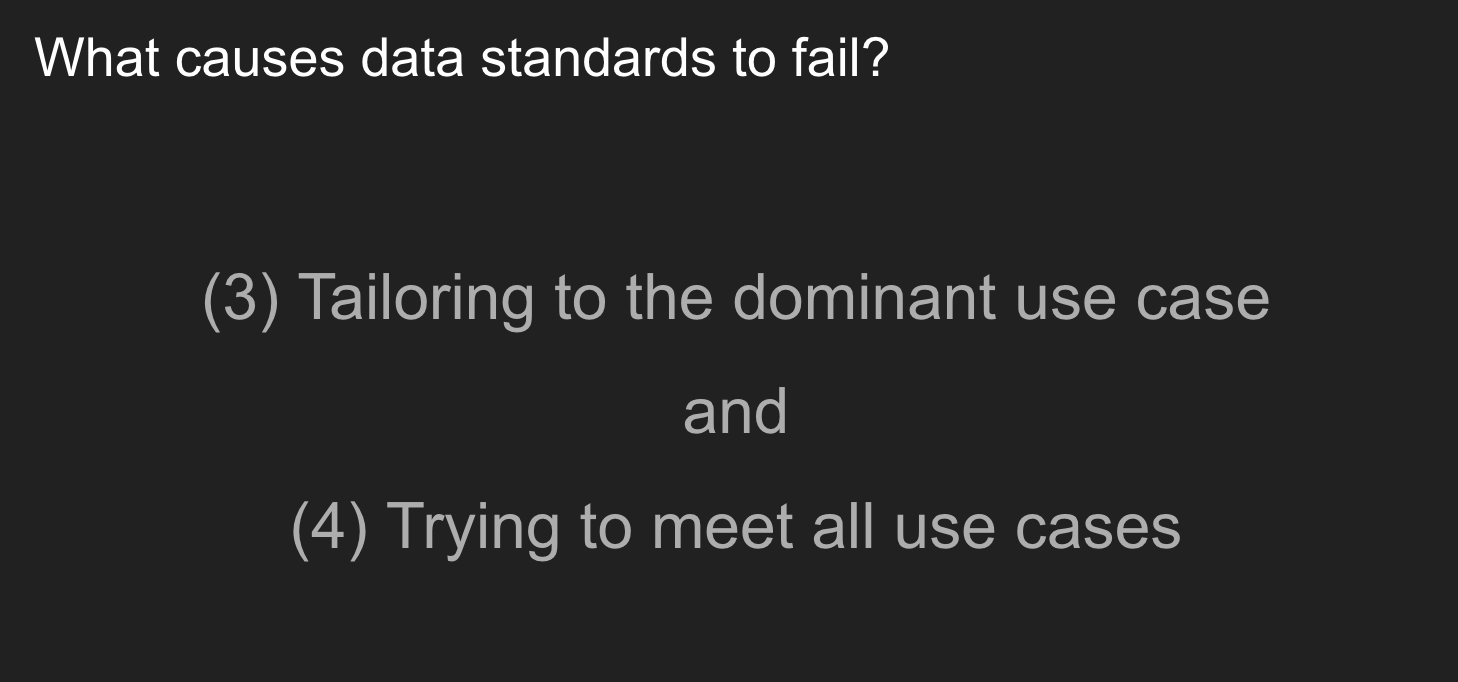

(3) Tailoring to the dominant use case and (4) Trying to meet all use cases

Standards are often developed because their author or sponsor has a particular problem or use-case in mind. For GTFS, the General Transit Feed Specification that drives many of the public transport directions you find in apps like GoogleMaps, that problem was ‘finding the next bus’ in Portland Oregon. That might be the question that 90% of data users come to the data with; but there are also people asking: “Is the bus stop and bus accessible to me as a wheelchair user?” or “Can we use this standard to describe the informal Matatu routes in Nairobi where we don’t have fixed bus stop locations?”

A brittle standard that only focusses on the dominant use case will likely crowd out space for these other questions to be answered. But a standard that was designed to try and cater for every single user need would likely collapse under its own weight. In the GTFS case, this has been handled by an open governance process that has allowed disability information to become part of the standard over time, and an openness to local extensions.

There is an art and an ethics of standardisation here – and it needs interdisciplinary teams. Which brings me to recap my final learning on where things can go wrong, and what we need to do to design standards well

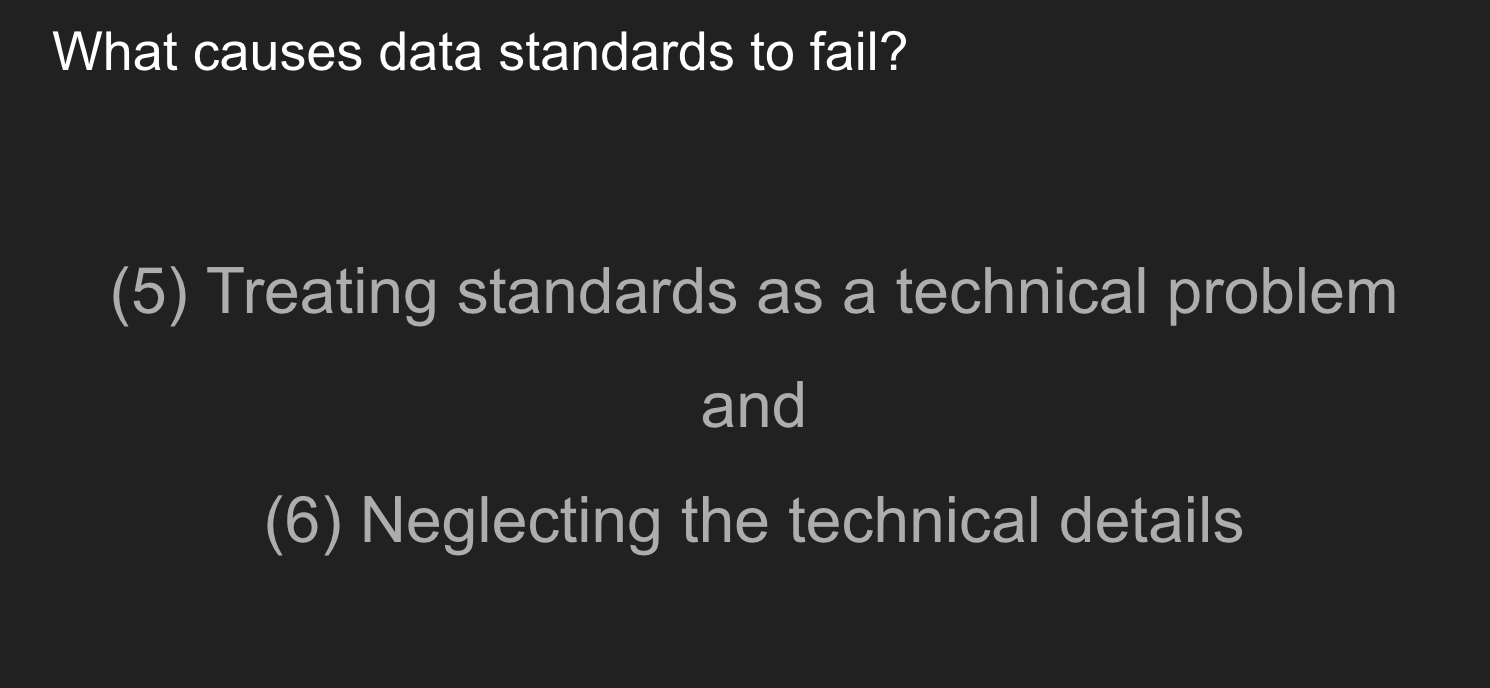

(5) Treating standards as a technical problem and (6) Neglecting the technical details

I suspect many here would not self-identify as ‘data experts’: yet everyone here could have a role to play in data standard development and adoption. Data standards are, at their core, a solution to coordination and collaboration problems, and making sure they work as such requires all sorts of skills, from policy, programme and institution design, to stakeholder engagement and communications.

But – at the same time – data standards face real technical constraints, and require creative technical problem solving.

Without technical expertise in the room after all, we may well end up turning up a month late.

Coda

I called this talk ‘Fostering open ecosystems’ because we face some very real risks that our digital futures will not be open and generative without work to create open standards. As the perceived value of data becomes ever higher, Silicon Valley capital may seek to capture the data spaces essential to solving development challenges. Or we may simply end up with development data locked in silos created by our failures to coordinate and collaborate. A focus on data standards is no magic bullet, but it is part of the pathway to create the future we need.