Yesterday the UK Government published, a year late, it’s most recent Open Government Partnership National Action Plan. It would be fair to say that civil society expectations for the plan were low, but when you look beyond the fine words to the detail of the targets set, the plan appears to limbo under even the lowest of expectations.

For example, although the Ministerial foreword acknowledges that “The National Action Plan is set against the backdrop of innovative technology being harnessed to erode public trust in state institutions, subverting and undermining democracy, and enabling the irresponsible use of personal information.”, the furthest the plan goes in relation to these issues is a weak commitment to “maintain an open dialogue with data users and civil society to support the development of the Government’s National Data Strategy.” This commitment has supposedly been ‘ongoing’ since September 2018, yet try as I might to find any public documentation of how the government is engaging around the data strategy – I’m drawing a blank. Not to mention that there is absolutely zilch here about actually tackling the ways in which we see democracy being subverted, not only through use of technology, but also through government’s own failures to respond to concerns about the management of elections or to bring forward serious measures to tackle the illegal flow of money into party and referendum campaigning. For work on open government to be meaningful we have to take off the tech-goggles, and address the very real governance and compliance challenges harming democracy in the UK. This plan singularly fails at that challenge.

In short, this is a plan with nothing new; with very few measurable targets that can be used to hold government to account; and with a renewed conflation of open data and open government.

Commitment 3 on Open Policy Making, to “Deliver at least 4 Open Policy Making demonstrator projects” have suspicious echoes of the 2013 commitment 16 to run “at least five ‘test and demonstrate projects’ across different policy areas.”. If central government has truly “led by example” on “increasingly citizen participation” as the introduction to this plan claims, then it seems all we are every going to get are ad-hoc examples. Evidence of any systemic action to promote engagement is entirely absent. The recent backsliding on public engagement in the UK vividly underscored by the fact that commitment 8 includes responding by November 2019 to a 2016 consultation. Agile, iterative and open government this is not.

Commitment 6 on an ‘Innovation in Democracy Programme’ involves token funding to allow a few local authority areas to pilot ‘Area Democracy Forums’, based on a citizens assembly models – at the same time that the government refuses to support any sort of participatory citizen dialogue to deal with pressing issue of both Brexit and Climate Change. The contract to deliver this work has already been tendered in any case, and the only targets in the plan relate to ‘pilots delivered’ and ‘evaluation’. Meaningful targets that might track how far progress has been made in actually giving citizens power over decisions making are notably absent.

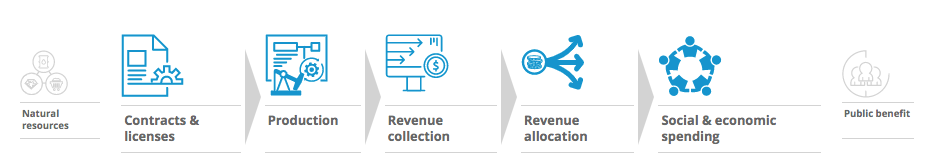

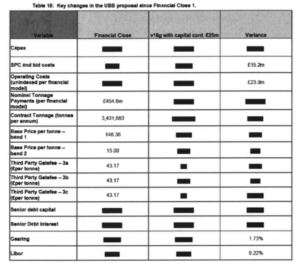

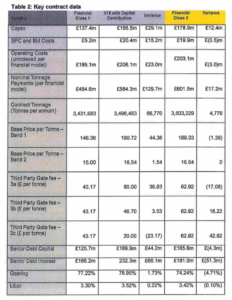

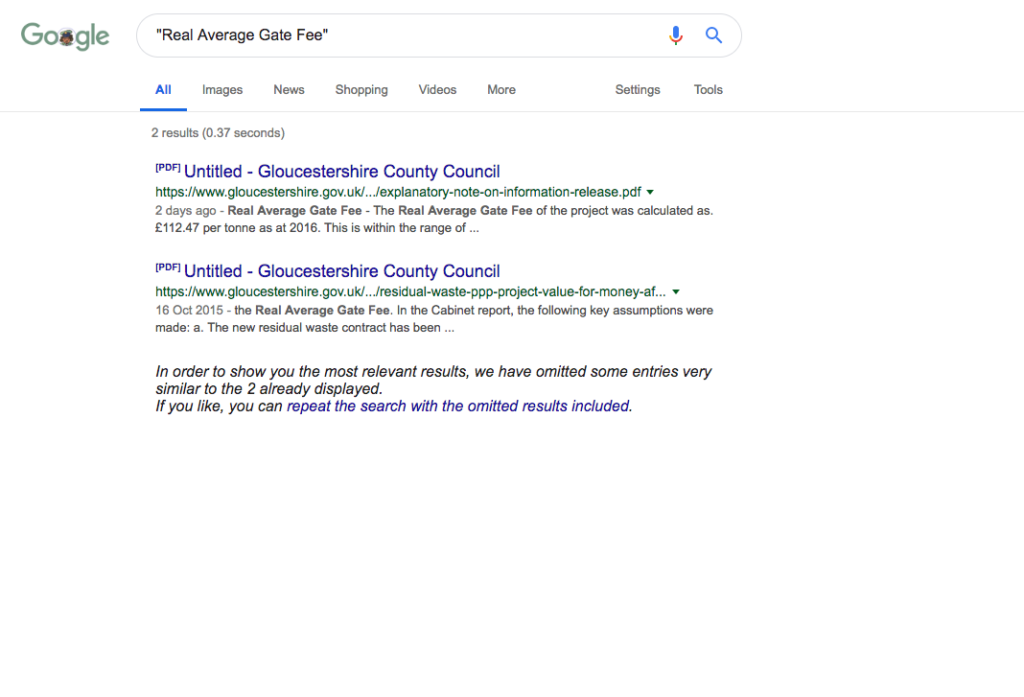

The most substantive targets can be found under commitments 4 and 5 on Open Contracting and Natural Resource Transparency (full disclosure: most of the Open Contracting targets come from draft content I wrote when a member of the UK Open Contracting Steering Group). If Government actually follows through on the commitment to “Report regularly on publication of contract documents, and extent of redactions.”, and this reporting leads to better compliance with the policy requirements to disclose contracts, there may even be something approaching transformative here. But, the plan suggests such a commitment to quarterly reporting should have been in place since the start of the year, and I’ve not yet tracked down any such report.

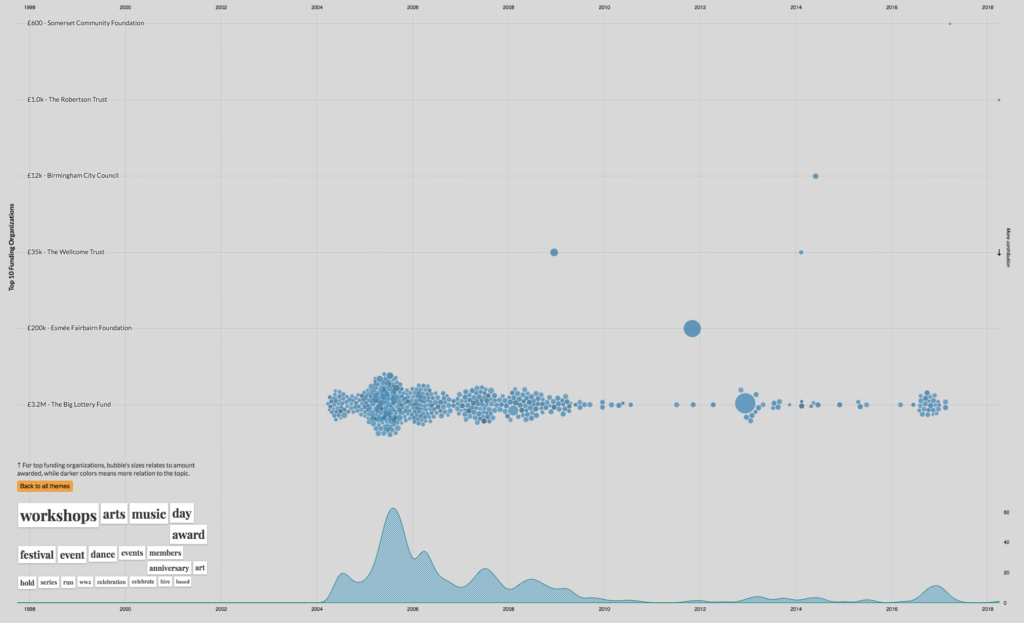

Overall these commitments are about house-keeping: moving forward a little on the compliance with policy requirements that should have been met long ago. By contrast, the one draft commitment that could have substantively moved forward Open Contracting in the UK, by shifting emphasis to the local level where there is greatest scope to connect contracting and citizen engagement, is the one commitment conspicuously dropped from the final National Action Plan. Similarly, whilst the plan does provide space for some marginal improvements in grants data (Commitment 1), this is simply a continuation of existing commitments.

I recognise that civil servants have had to work long and hard to get even this limited NAP through government given the continued breakdown normal Westminster operations. However, as I look back to the critique we wrote of the first UK OGP NAP back in 2012, it seems to me that we’re back where we started or even worse: with a government narrative that equates open government and open data, and a National Action Plan that repackages existing work without any substantive progress or ambition. And we have to consider when something so weak is actually worse than nothing at all.

I resigned my place on the UK Open Government Network Steering Group last summer: partly due to my own capacity, but also because of frustration at stalled progress, and the co-option of civil society into a process where, instead of speaking boldly about the major issues facing our public sphere, the focus has been put on marginal pilots or small changes to how data is published. It’s not that those things are unimportant in and of themselves: but if we let them define what open government is about – well, then we have lost what open government should have been about.

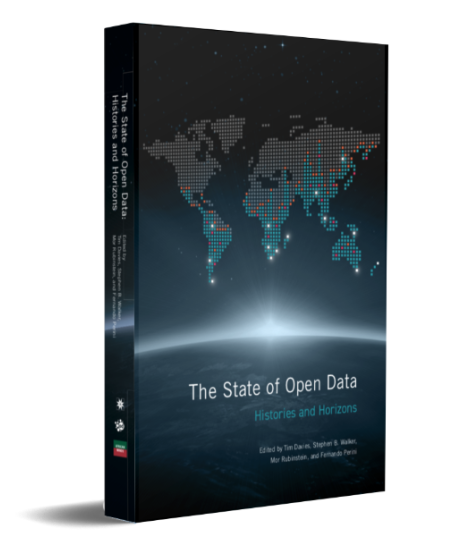

And even we do allow the OGP to have a substantial emphasis on open data, where the UK government continues to claim leadership, the real picture is not so rosy. I’ll quote from Rufus Pollock and Danny Lämmerhirt’s analysis of the UK in their chapter for the State of Open Data:

“Open data lost most of its momentum in late 2015 as government attention turned to the Brexit referendum and later to Brexit negotiations. Many open data advisory bodies ceased to exist or merged with others. For example, the Public Sector Transparency Board became part of the Data Steering Group in November 2015, and the Open Data User Group discontinued its activities entirely in 2015. There have also been political attempts to limit the Freedom of Information Act (FOIA) based on the argument that opening up government data would be an adequate substitute. There are still issues around publishing land ownership information across all regions, and some valuable datasets have been transferred out of government ownership avoiding publication, such as the Postal Address File that was sold off during the privatisation of the Royal Mail.”

The UK dropped in the Open Data Barometer rankings in 2017 (the latest data we have), and one of the key commitments from the last National Action Plan to “develop a common data standard for reporting election results in the UK” and improve crucial data on elections results had ‘limited’ progress according to the IRM, demonstrating a poor recent track record from the UK on opening up new datasets where it matters.

So where from here?

I generally prefer my blogging (and engagement) to be constructive. But I’m hoping that sometimes, the most constructive thing to do, is to call out the problems, even when I can’t see a way to solutions. Right now, it feels to me as though the starting point must be to recognise:

- The UK Government is failing to live up to the Open Government Declaration.

- UK Civil Society has failed to use the latest OGP NAP process to secure any meaningful progress on the major open government issues of the day.

- The Global OGP process is doing very little to spur on UK action.

It’s time for us to face up to these challenges, and work out where we head from here.